Doomiest Images of 2022

31 December 2022 (Desdemona Despair) – The year 2022 produced the usual terrible images of abrupt climate change, from record-breaking floods in Australia to drought-stricken refugees in Africa. But 2022 had a new subject for doom imagery: large-scale war in Europe, when Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

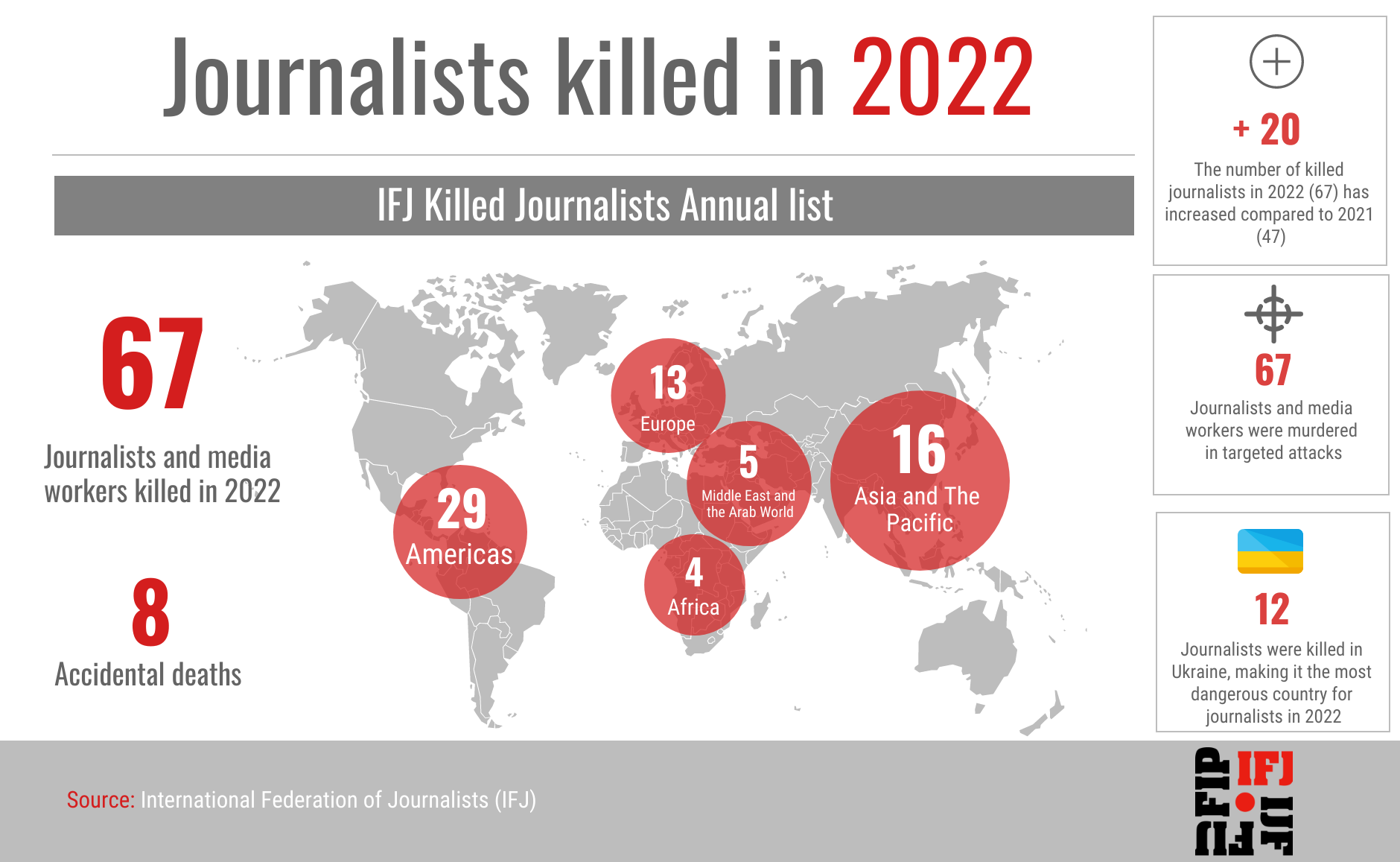

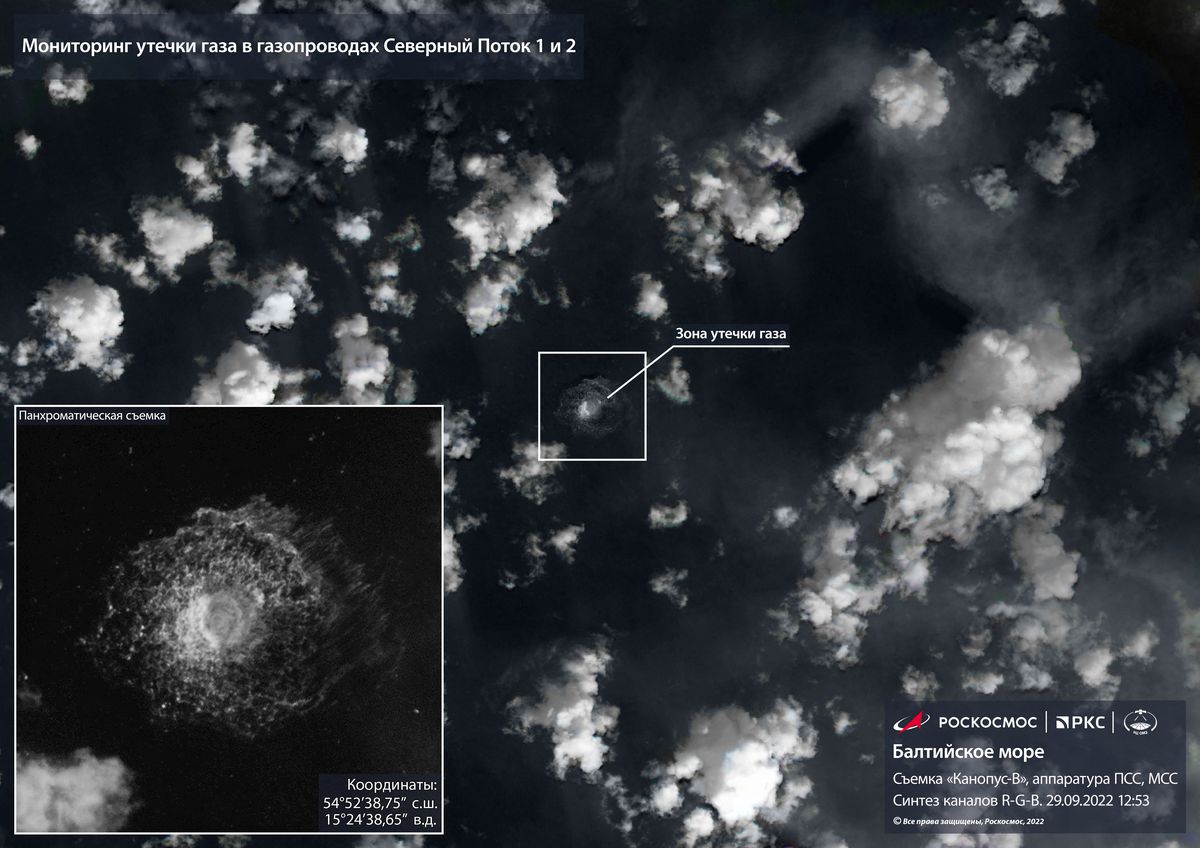

War in Europe

Not since the Serbian genocide against Bosnia has Europe seen a brutal war that displaced millions of people. Russia’s attack on Ukraine is possibly the most photographed war in history, producing a torrent of imagery that could fill an encyclopedia. Desdemona considered starting another blog dedicated to war news but realized it would be a full-time job.

The disruption of agricultural exports from Ukraine and Russia affected millions of people who live thousands of miles from the front lines, worsening the already-dire situations of starving people in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere.

Even before the Russian invasion, world hunger had risen in 2021, with 2.3 billion people severely or moderately hungry, as the human population topped 8 billion.

Freshwater depletion

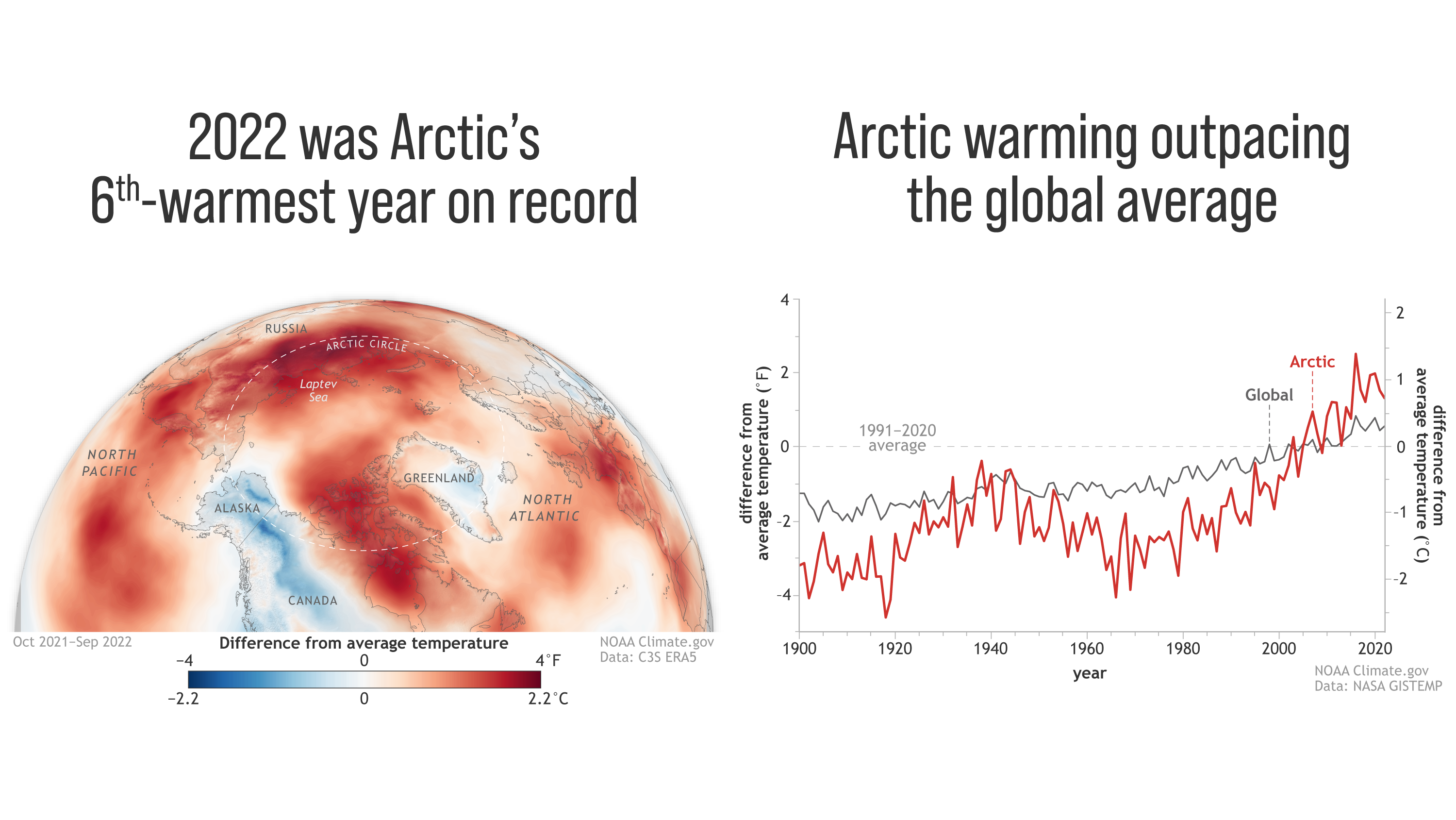

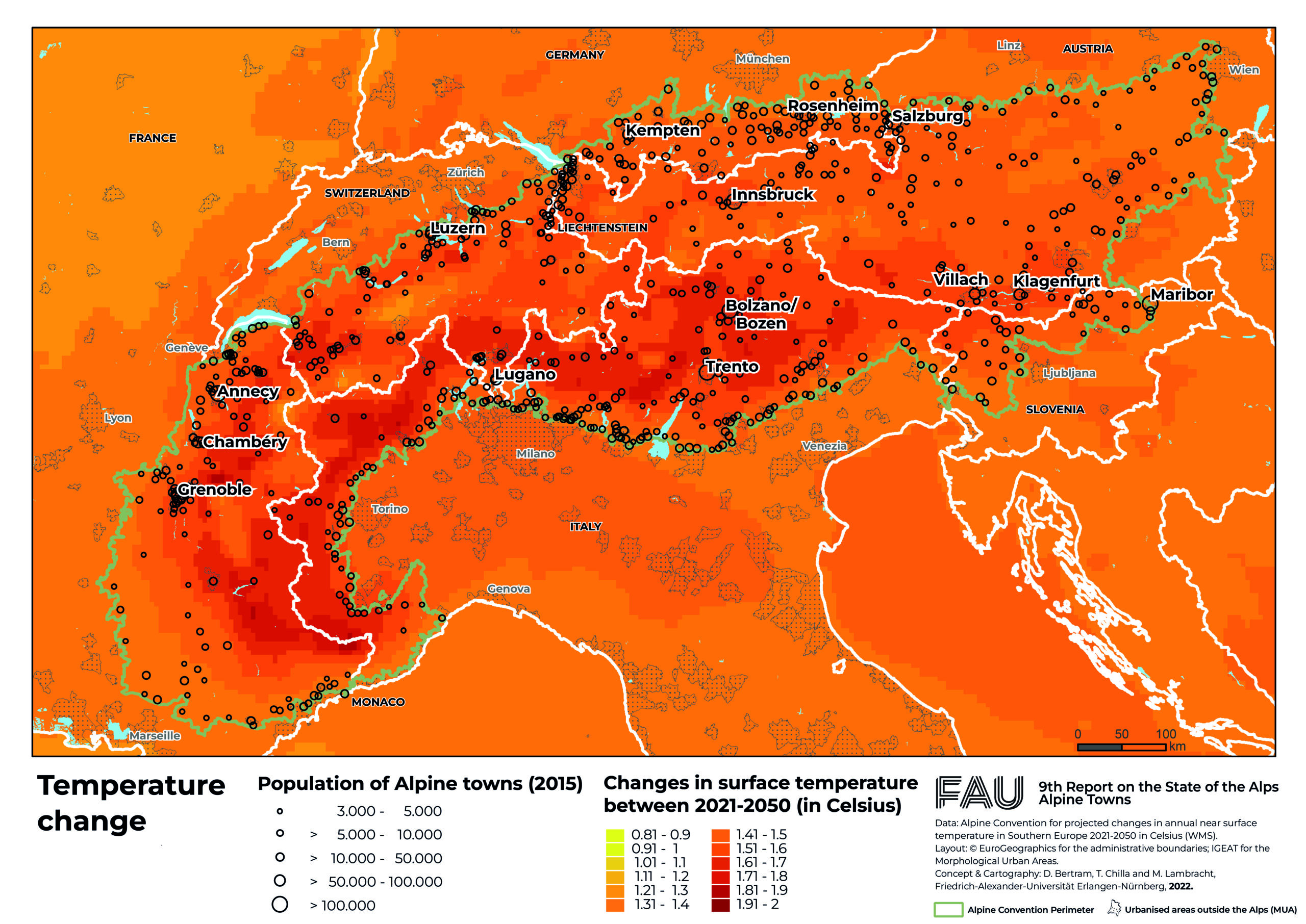

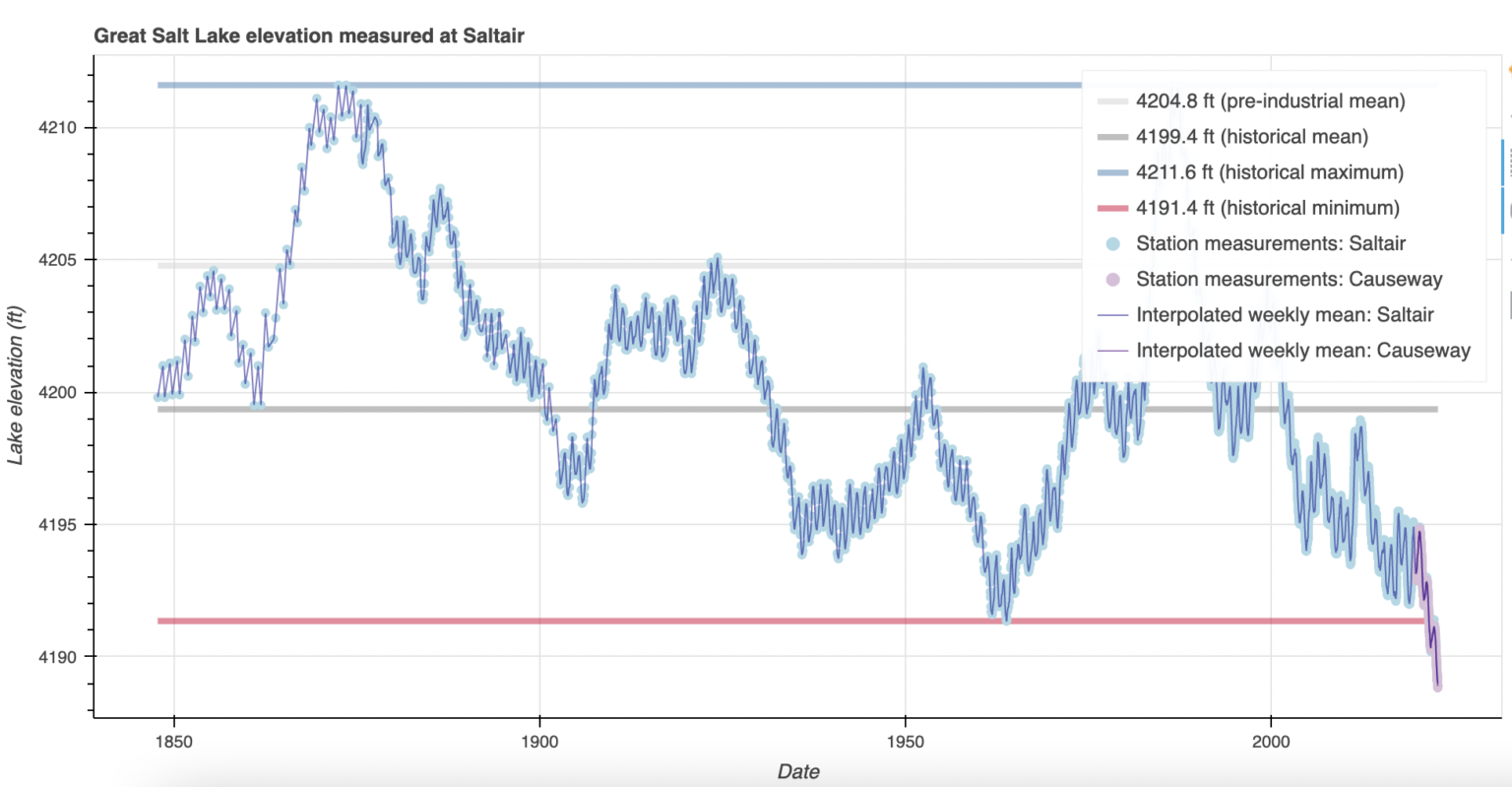

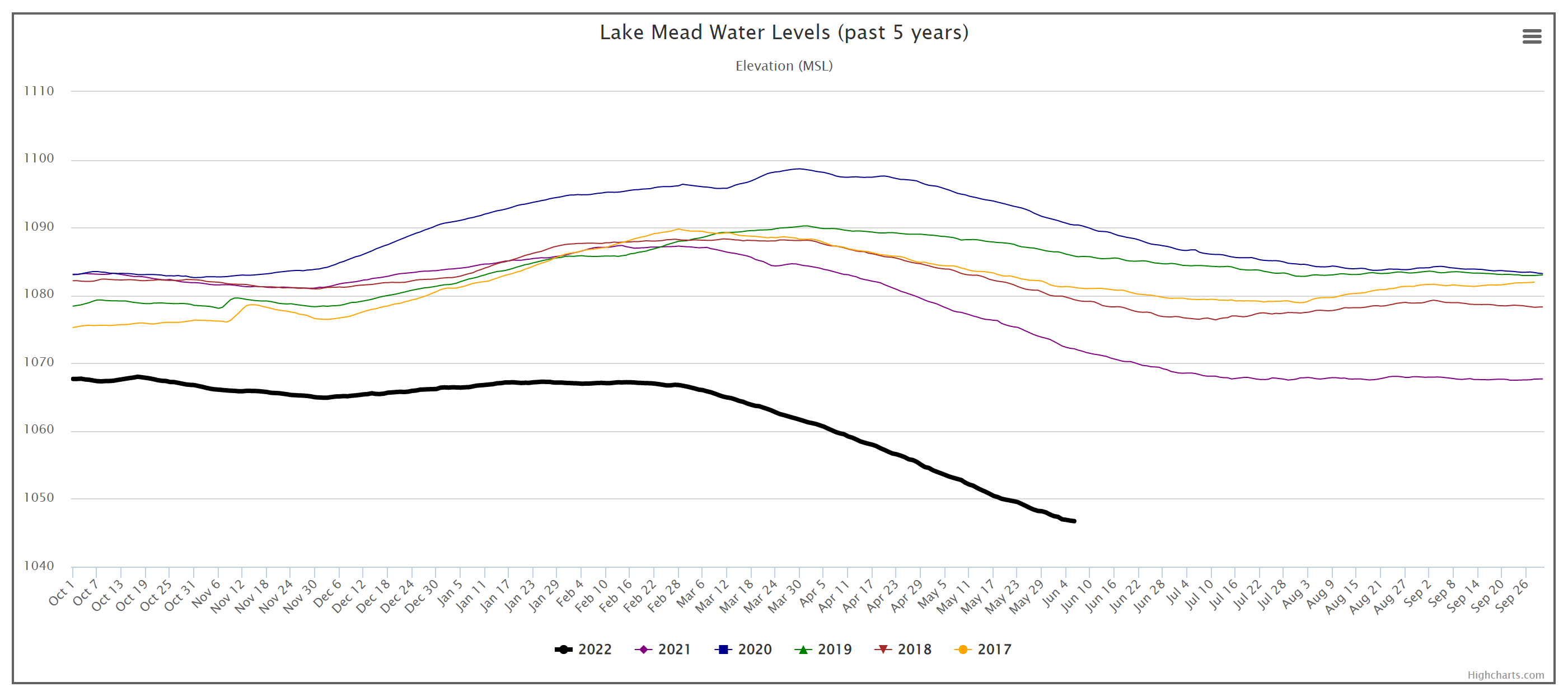

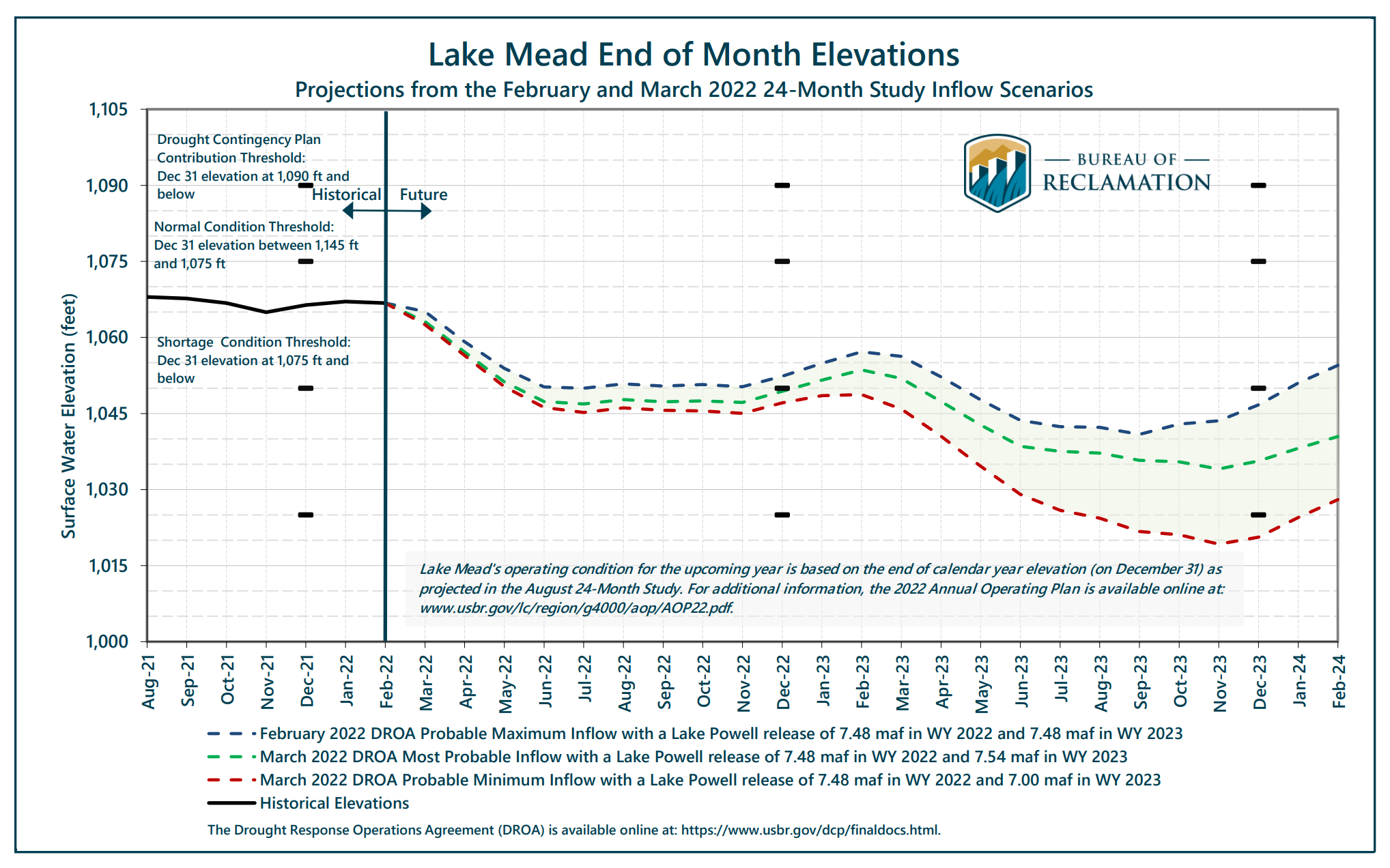

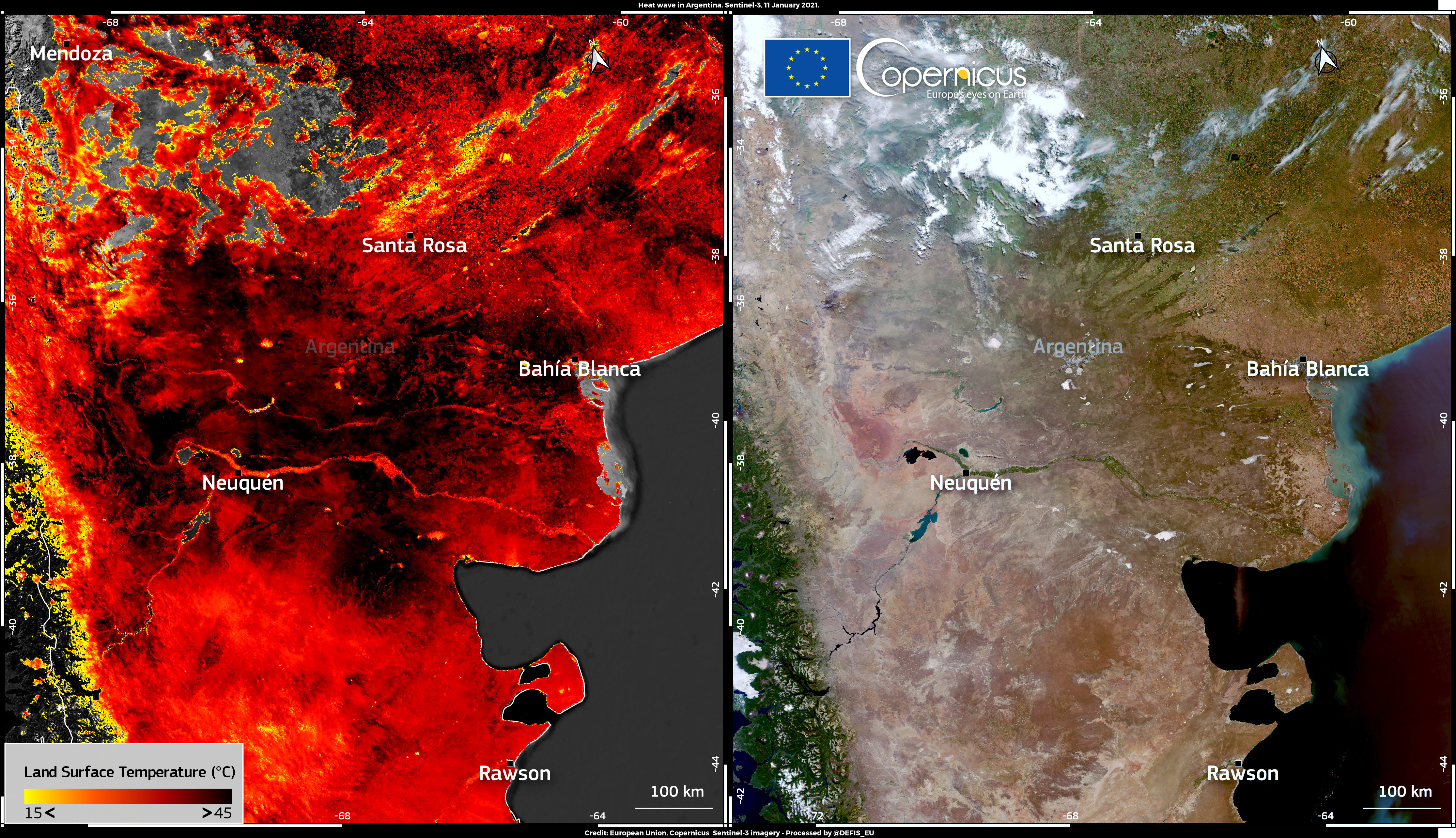

The record-breaking heatwaves and droughts of 2022 brought freshwater depletion to the heart of the developed world. Water levels in the great U.S. reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, fell to the lowest levels since their construction. In Europe, entire rivers dried up, stranding ships and threatening crops. In Germany, drought combined with a bark beetle infestation to denude wide swaths of the Harz forest.

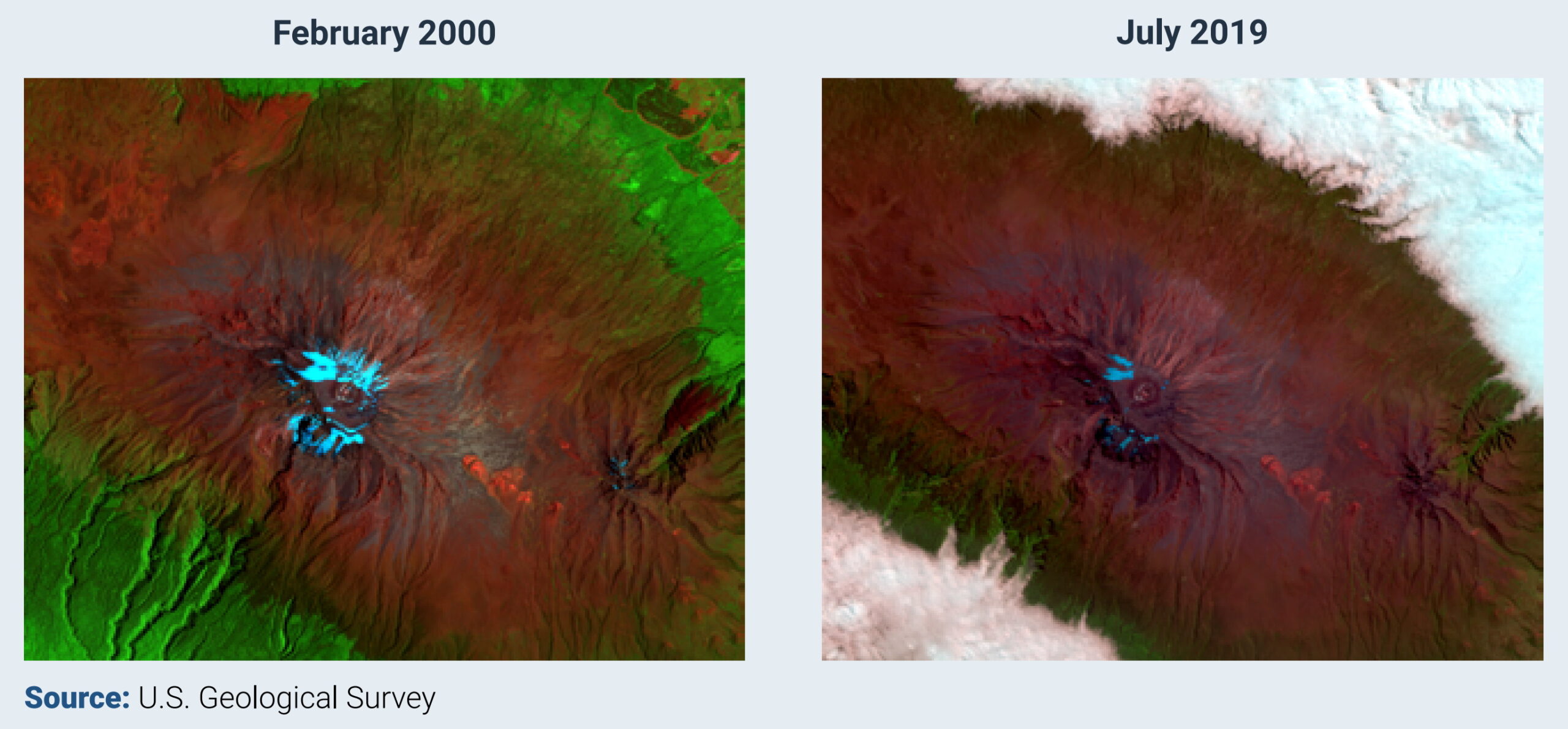

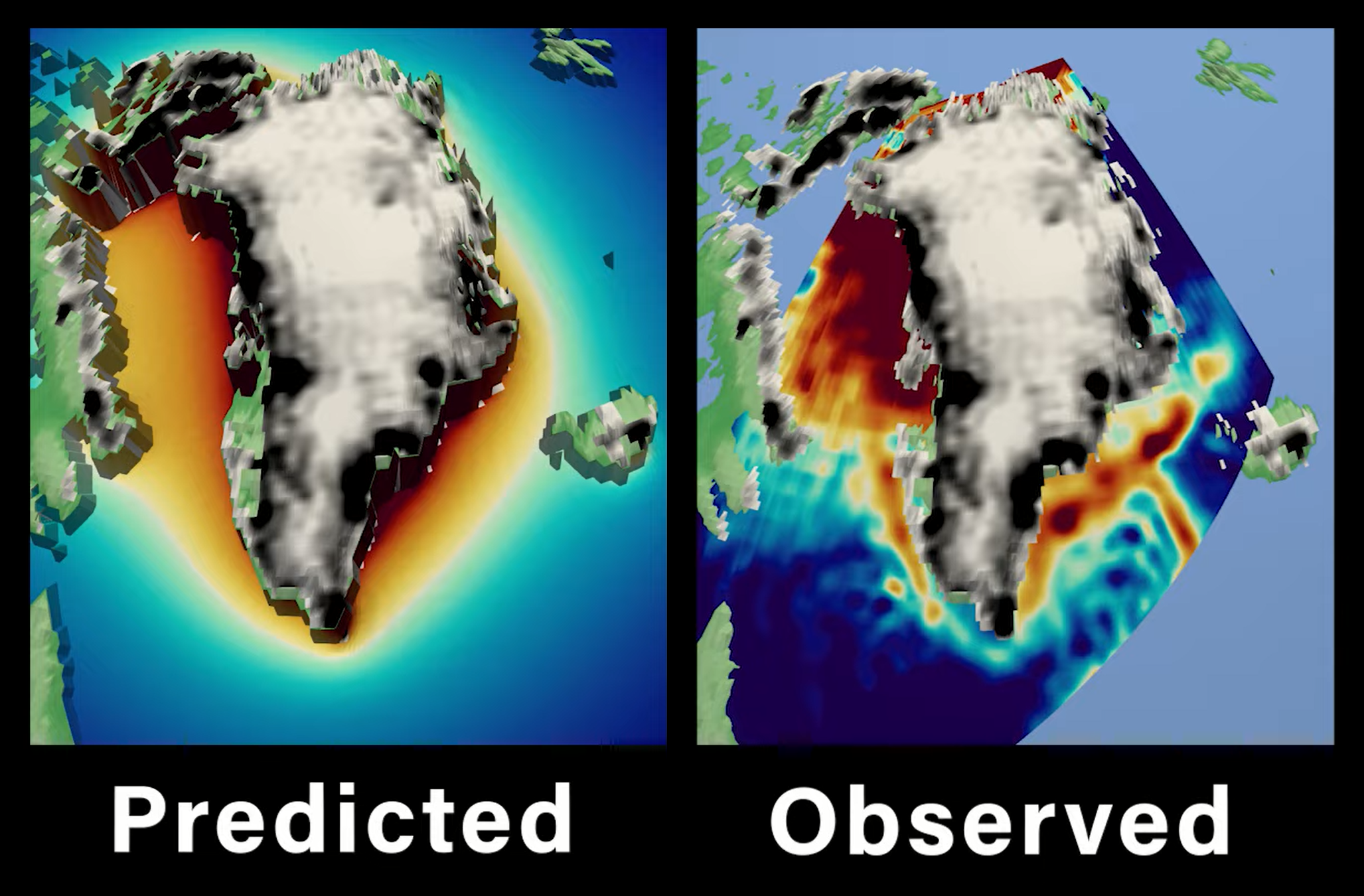

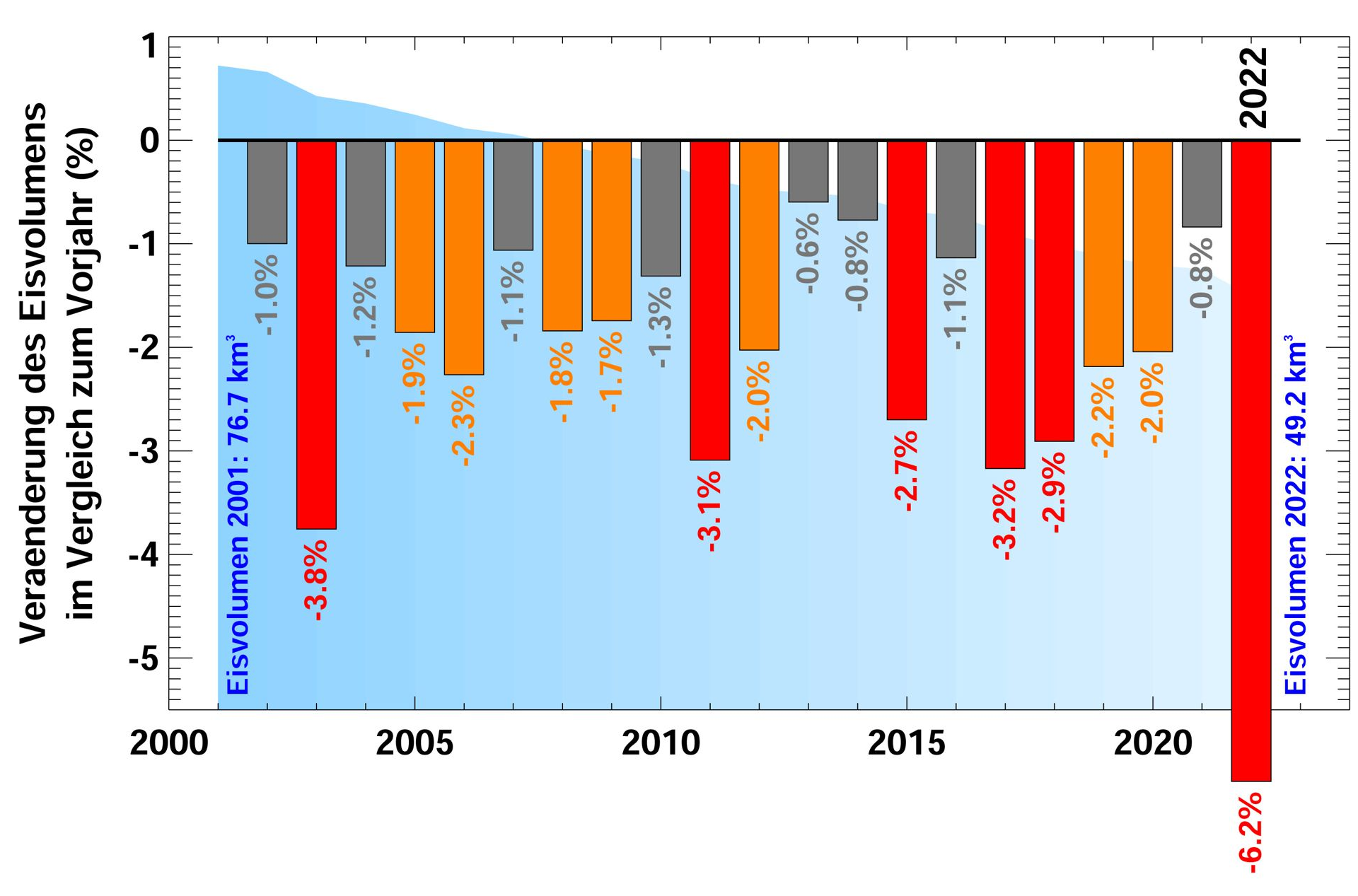

It was an especially bad year for Europe’s glaciers, with more than 6 percent of the total ice volume lost due to the winter snow drought and continuous heatwaves in summer, smashing all previous ice-melt records. Before 2022, years with an ice loss of 2 percent were described as “extreme”. The decline of Alpine glaciers heralds an unprecedented era of water scarcity in Europe.

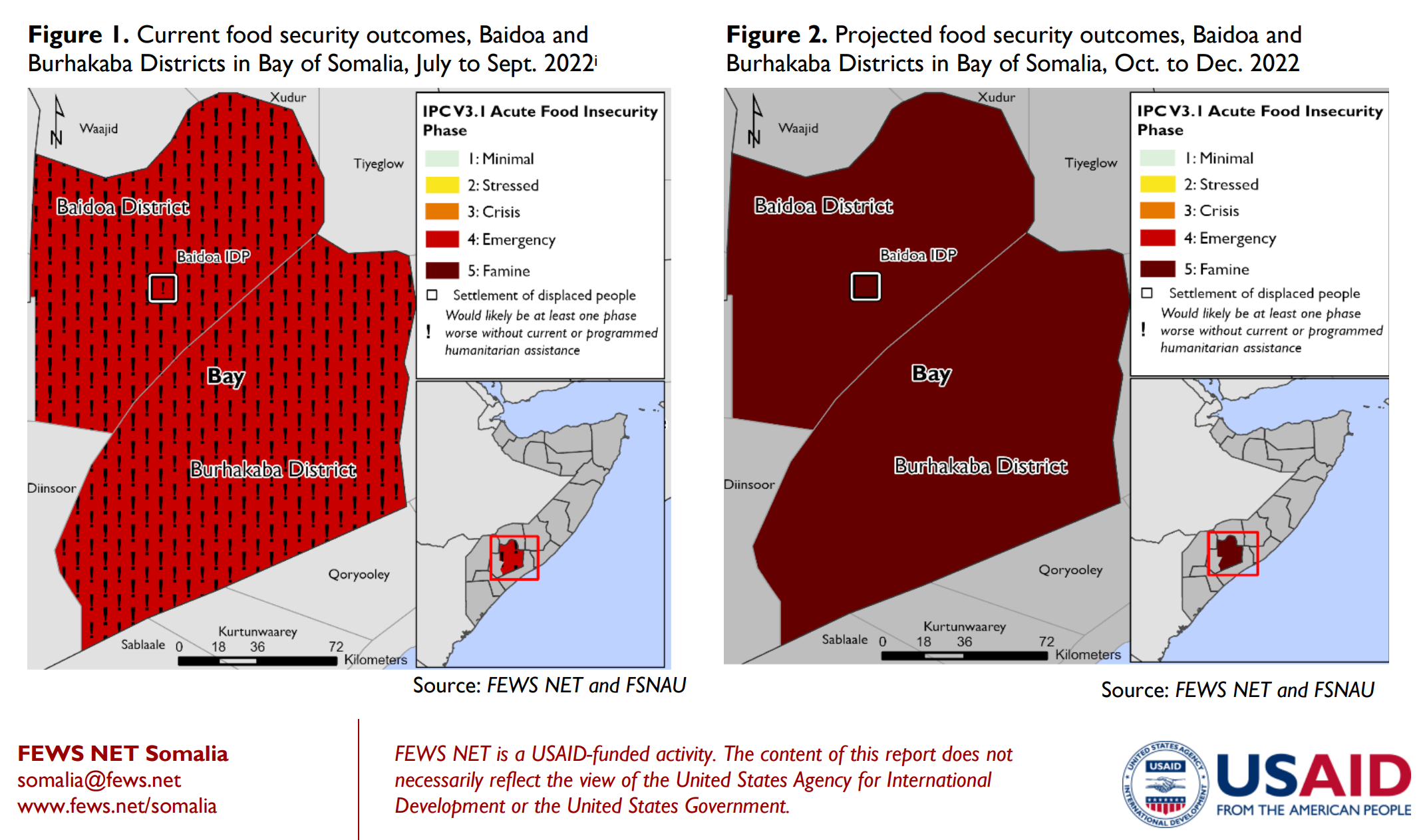

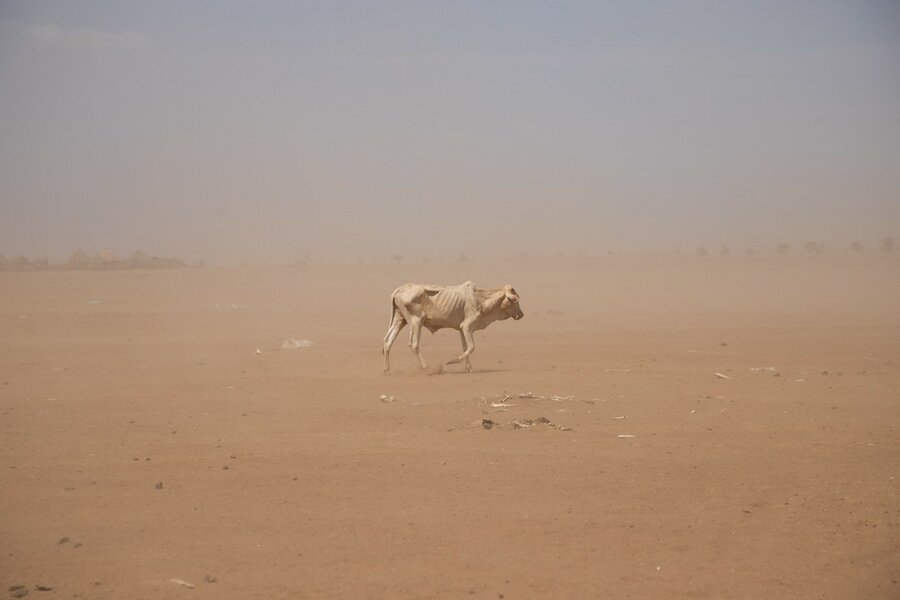

In the Horn of Africa, the fifth consecutive rainy season failed in 2022, deepening the misery of millions in Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia. More than 20 million children face starvation. More than 9.5 million livestock have died already, and more are expected to perish in the months ahead, including at least 30 million weakened and emaciated livestock in Ethiopia alone. The toll on wildlife is unknown but undoubtedly enormous.

Flooding

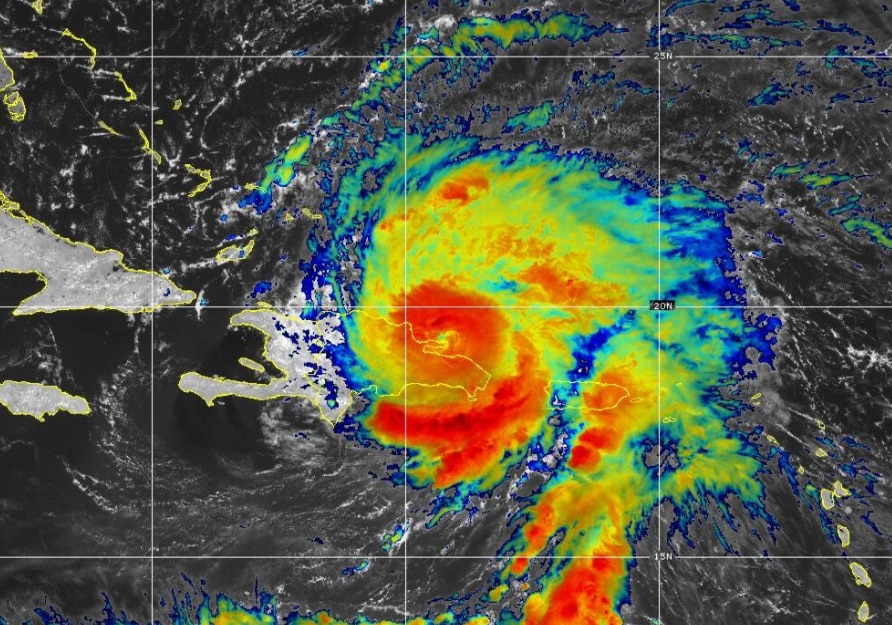

Global warming doesn’t just cause more frequent and longer heatwaves and droughts – it drives increased evaporation from the oceans and increases atmospheric water vapor, which is why it’s often said that “a warmer world is a wetter world.”

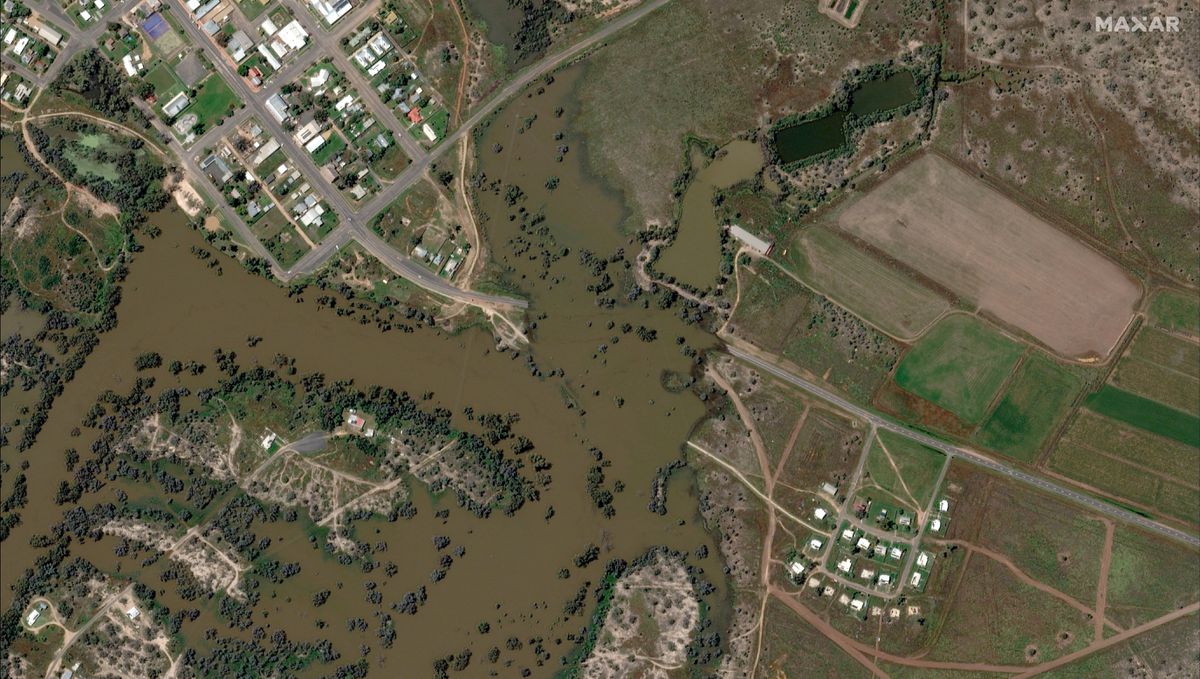

In 2022, much of the world experienced record-breaking floods. Disastrous inundations occurred in Australia in March and October, causing serious discussion about the previously unthinkable mitigation strategy of “managed retreat” from increasingly flood-prone areas that are essentially becoming uninhabitable.

Historic floods struck South Sudan for the fourth consecutive year. Nigeria saw its worst floods in a decade, displacing 1.3 million people. “Unprecedented” floods struck Bangladesh and northeastern India. Record rains in China’s southern provinces forced millions of people to relocate even as the country’s north experienced abnormally high temperatures. The heaviest rains and flooding in 60 years killed at least 443 people in South Africa.

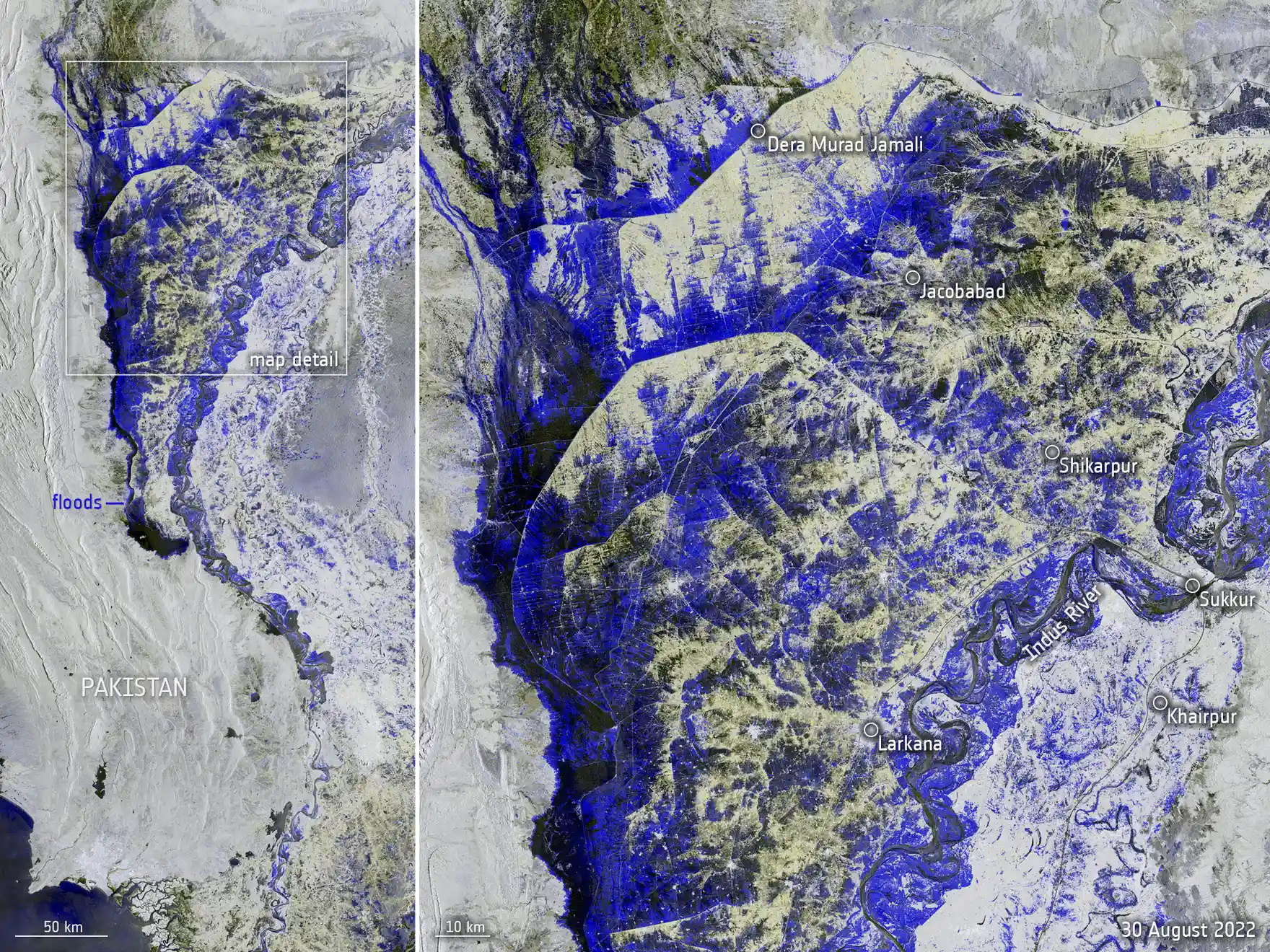

But no single flooding event matched the catastrophic rainfall that struck Pakistan from June to October 2022, inundating one-third of the country.

Waseem Ahmad, CEO of Islamic Relief Worldwide, spoke from the northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, saying he had been in the country for the 2010 floods, which killed nearly 2,000 people, but this was worse.

“The situation … is absolutely chaos everywhere. People are on the roadside, waiting for humanitarian assistance, like water, food, shelter, and this is unprecedented in the history of Pakistan. In 22 years of my experience as a humanitarian aid worker, I never saw such destruction caused by floods.”

By October, it was clear that a massive reconstruction effort was necessary, with more than 33 million people affected by the calamity, costing the nation $30 billion in damages as the torrential rains had destroyed bridges, crops, highways, and other infrastructure. The World Bank estimated the cost to rebuild to be greater than $16 billion. In December, Pakistan’s prime minister said his country desperately needed aid for 20 million flood victims to survive the harsh winter.

Desperate measures

Humanity’s desperate attempts to reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels are driving the development of immensely destructive rare earth mines that are frequently unregulated and illegal. In Myanmar, the rush to power “green technologies” has caused the rapid expansion of illegal mining of heavy rare earth minerals, fueling human rights abuses, environmental destruction, and local militias linked to the brutal military regime.

In the Amazon River basin, illegal gold mines destroy the rainforest and pollute the waters with extractive chemicals like mercury. Wildcat miners easily evade supply-chain restrictions like the Responsible Minerals Initiative, with the help of corrupt local governments.

David Soud, head of research at I.R. Consilium, who has researched illegal gold flows in South America, remarked, “In Brazil, as in so many gold-producing countries, illegality enters into the supply chain very early on, so it’s essential to get better visibility on what happens upstream. Refiners are often culpable for failures in due diligence and need to be held to strict standards so that questionably sourced gold doesn’t get laundered into the legitimate supply chain.”

In spite of the rush to build out the renewable energy infrastructure, high energy prices in 2022 caused a sudden resurgence in the use of coal, the worst of the climate-damaging fuels. In India, heatwaves drove the annual power demand to grow at the fastest rate in at least 38 years, causing a coal shortage. The government planned to reopen more than 100 coal mines that were previously considered financially unsustainable. In the Czech Republic, demand for brown coal – the cheapest and most energy inefficient form – jumped by almost 35 percent in the first nine months of 2022 over the previous year. In Pennsylvania, a company planned to burn coal waste to power bitcoin mining.

Testing the humanitarian response system “to its limits”

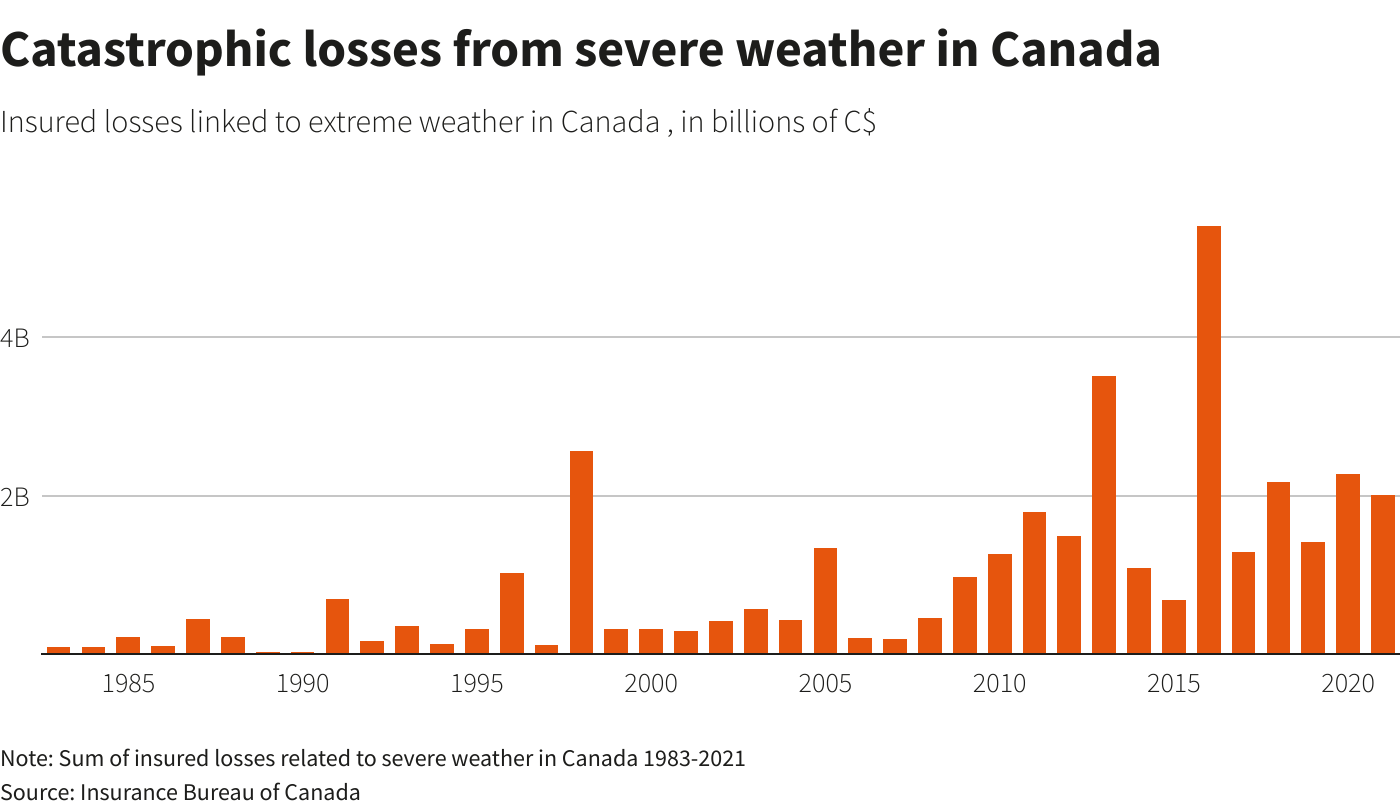

By December 2022, it was clear that this was a year like no other. The United Nations appealed for a record $51.5 billion in aid money for 2023, with tens of millions of additional people expected to need assistance, testing the humanitarian response system “to its limits”.

For the first time ever, ten countries had individual appeals of more than $1 billion: Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

U.N. Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffiths remarked, “Humanitarian needs are shockingly high, as this year’s extreme events are spilling into 2023,” citing Russia’s war on Ukraine and drought in the Horn of Africa.

The Diva of Doom

Des posted a lot of photos in 2022, but there were a few that hold a special place in Desdemona’s heart: selfies taken by the late “Themist“, Gail Zawacki, who died in 2022 at the age of 67. Gail was a prolific blogger and a fierce defender of ecosystems, focusing specifically on the plight of trees and the effects of industrial pollution on them. She was such an inspiration that Des wrote an obituary about her, The Diva of Doom: Remembering the late, great Gail Zawacki. If she had lived just two months longer, she would have seen a study that vindicated her years of struggle to alert humans to the danger of the ongoing mass tree die-off: At least one-third of Earth’s trees face extinction. Gail was never shy about engaging scientists, and Des has no doubt that she would have had some great discussions with the authors of this paper.

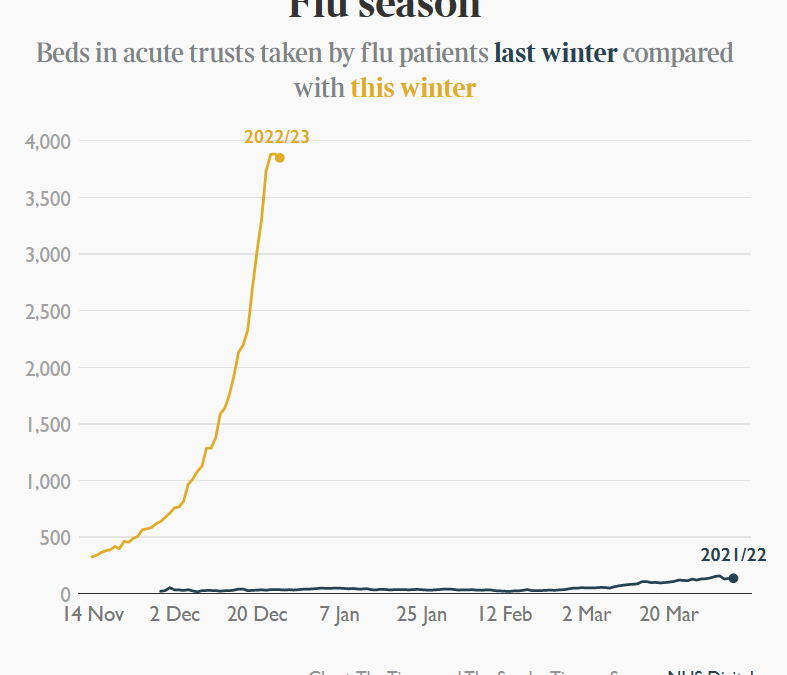

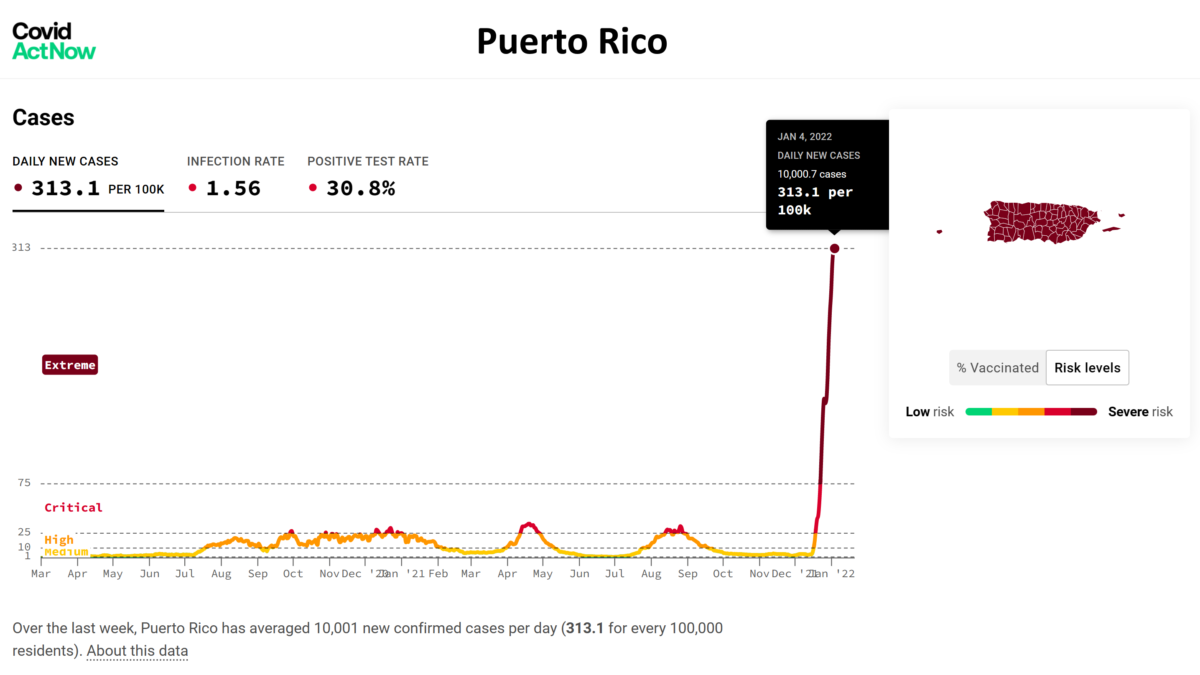

- Don’t miss the doomiest graphs for 2022.

- For the doomiest content going back to 2010, check out the Doomiest Images and Graphs Index.