Facing “dead pool” risk, California braces for painful water cuts from Colorado River – “It’s very scary. If there’s no river, then you have no community.”

By Ian James

4 September 2022

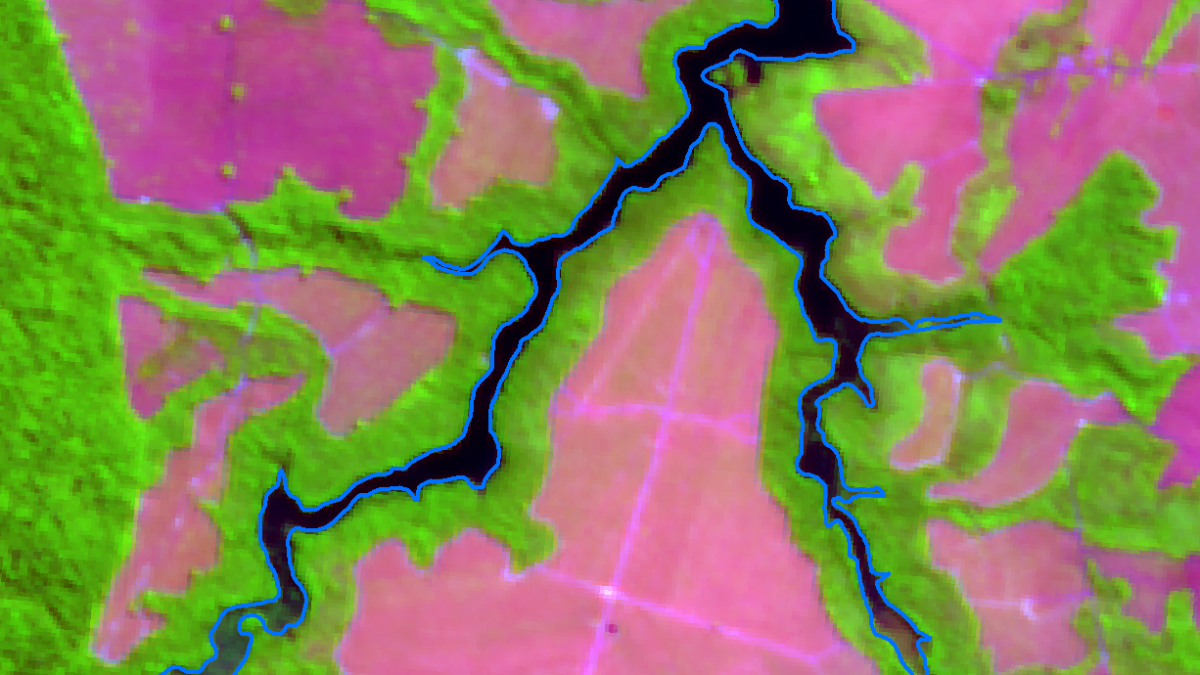

(Los Angeles Times) – California water districts are under growing pressure to shoulder substantial water cutbacks as the federal government pushes for urgent solutions to prevent the Colorado River’s badly depleted reservoirs from reaching dangerously low levels.

California has the largest water entitlement of any state on the Colorado River, totaling 4.4 million acre-feet. The water flows to farmlands in the Imperial and Coachella valleys, and to cities from La Quinta to Los Angeles. Reducing the state’s use of the river could involve expanding drought restrictions in cities, increasing incentives for property owners to remove grass, and paying farmers to cut the amount of water they use to irrigate their fields.

Managers of districts that rely on the Colorado River have been talking about how much water they may forgo. So far, they haven’t publicly revealed how much they may commit to shore up the declining levels of Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir. But state and local water officials say there is widespread agreement on the need to reduce water use next year to address the shortfall.

Without major reductions, the latest federal projections show growing risks of Lake Mead and Lake Powell approaching “dead pool” levels, where water would no longer pass downstream through the dams. Though the states haven’t agreed on how to meet federal officials’ goal of drastically reducing the annual water take by 2 million to 4 million acre-feet, the looming risks of near-empty reservoirs are prompting more talks among those who lead water agencies.

“Everyone agrees that we have to work together to take action to stabilize the Colorado River system,” California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot said. “The status quo is simply untenable. We are looking at these reservoirs dipping below dead pool in coming years if we don’t come together to take extraordinary actions.”

Federal officials from the Interior Department and the Bureau of Reclamation recently met in Salt Lake City with water managers from the seven states that rely on the Colorado River. Some who attended the closed-door meeting on Aug. 26 said that the discussion was productive, and that Assistant Interior Secretary Tanya Trujillo and Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton expressed willingness to work with the states to develop plans for water reductions.

Though Trujillo and Touton have stressed their interest in collaborating on solutions, they have also laid out plans that could bring additional federal leverage to bear. Their plan to reexamine and possibly redefine what constitutes “beneficial use” of water in the three Lower Basin states — California, Arizona and Nevada — could open an avenue to a critical look at how water is used in farming areas and cities.

How the government might wield that authority, or tighten requirements on water use, hasn’t been spelled out. The prospect of some type of federal intervention, though, has become one more factor pushing the states to deliver plans to take less from the river.

The Colorado River, long overused to supply farms and cities, has shrunk during a 23-year megadrought that research shows is being intensified by the hotter temperatures unleashed by the burning of fossil fuels.

Farmers in parts of Arizona are already dealing with major water cutbacks under a 2019 agreement, and Nevada has also taken cuts. But California, which has more senior water rights, has yet to see reductions under that deal.

Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said in a letter to the federal government this week that Arizona supports various proposals put forth by Nevada. They include improving water efficiency in agriculture, creating a regional program to help people with the costs of removing grass, and redefining “beneficial use” to eliminate “wasteful and antiquated water use practices.”

It’s difficult to say what might qualify as “wasteful” or “antiquated” in any reexamination, but “beneficial use” is a foundational principle in Western water law, with accepted uses enshrined in state laws including categories such as municipal, industrial, irrigation, recreation and mining, among other things, said Rhett Larson, a professor of water law at Arizona State University.

Because most water rights fall under state law, developing a new definition of “beneficial” would be complicated and could lead to lawsuits, Larson said. What might qualify as “waste” would also be hard to pin down, he said, because “one person’s waste is another person’s job.”

For centuries, Native Americans have visited Avi Kwa Ame, or Spirit Mountain, to seek religious visions and give thanks for the bounty of the Earth.

“I think the average voter probably thinks of water waste as things like water-slide parks and golf courses and grassy medians in the road,” Larson said. “While I agree that we need to remove nonproductive turf … when I think of waste, I think about it more in the sense of agriculture, since that’s where we could get the most savings.”

Others are also looking to agriculture. Leading Nevada water manager John Entsminger has pointed out that roughly 80% of the river’s flow is used for farming, and much of that is for thirsty crops like alfalfa, which is mainly grown for cattle.

Larson said he expects the focus to be on requiring more efficient water use, such as shifting away from flood irrigation toward drip and center-pivot irrigation systems. In some areas, water seeps into the ground along unlined dirt canals and evaporates from open canals. Larson said lining these canals with concrete would make sense, as would eventually covering canals with solar panels to reduce losses to evaporation.

Arizona and Nevada are calling for a look at “wasteful” water use as a way of prodding large California agencies like the Imperial Irrigation District to agree to substantial cutbacks, Larson said. It’s an indirect way, he said, for the two states to send a message that “California, your agriculture needs to be more efficient.”

For the next two or three years, we’re going to be right on the edge of dead pool in both of our major reservoirs.

Bart Fisher, vice president of the Palo Verde Irrigation District’s board

In June, Touton called for the states to come up with plans for major reductions within two months. But negotiations grew tense and acrimonious, and the talks didn’t produce a deal.

As wildfires become more extreme, some worry California will near a tipping point in which its forests emit more carbon dioxide than they absorb.

After the failure to reach an agreement, Entsminger criticized what he called the “unreasonable expectations of water users” and “drought profiteering proposals.” Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.) called for other states throughout the Colorado River Basin to “step up and do their part.”

The meeting in Salt Lake City apparently helped smooth over some of those tensions.

“By the end of the meeting, it was pretty warm and fuzzy,” said Bart Fisher, vice president of the Palo Verde Irrigation District’s board. “I thought it was Reclamation’s intent to try to really hit the reset button and get people working together again.”

The meeting helped create “some goodwill” among the parties, Fisher said, and “sets the stage for future discussions.”

Lake Mead now sits 28% full, while Lake Powell has declined to 25% of full capacity. Hot and dry conditions are forecast to continue across the watershed at least through the fall, and the reservoirs are projected to continue declining.

“For the next two or three years, we’re going to be right on the edge of dead pool in both of our major reservoirs,” Fisher said.

Years ago, scientists said climate change would bring a Colorado River crisis. Their warnings, which largely went unheeded, are now playing out.

The Palo Verde Irrigation District supplies water to farmers around the town of Blythe, next to the river.

Fisher, a third-generation farmer who grows broccoli, melons, wheat, and hay, said the risk that his community could entirely lose its water supply underscores the need for action.

“It’s very scary,” Fisher said. “If there’s no river, then you have no community.” [More]

Facing ‘dead pool’ risk, California braces for painful water cuts from Colorado River