Russia’s war on global food security – Russia’s blockade of Ukraine grain exports may cause starvation of 47 million people – “It will result in famine and destabilization and mass migration around the world”

By Anders Åslund

1 June 2022

(Atlantic Council) – Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine is also a war on global food security. In February 2022, Russia blockaded all of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, through which all its bulk exports were being shipped. The ports remain closed, with no opening in sight. David Beasley, the executive director of the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), recently warned, “When a country like Ukraine that grows enough food for 400 million people is out of the market, it creates market volatility, which we are now seeing.”

Beasley made clear how grave the crisis is as Russian forces preventing Ukraine’s exports from getting to market threaten to plunge vulnerable populations into peril. “Truly, failure to open those ports in Odesa region will be a declaration of war on global food security,” said Beasley. “And it will result in famine and destabilization and mass migration around the world.”

In recent years, Ukraine’s export revenues from both goods and services have surged, thanks to booming agricultural production and rising commodity prices. They soared from $124 billion in 2020 to a record of $166 billion in 2021, while Ukraine’s gross domestic product (GDP) was $200 billion. Meanwhile, the share of agriculture in Ukraine’s export revenues from goods increased from 26 percent in 2012 to 45 percent in 2020.

Russia has further aggravated this food crisis by bombing and burning grain storage in the south and east of Ukraine, by stealing hundreds of thousands of tons of grain, and by exporting it on its own ships, primarily to its ally Syria.

Russia’s war on Ukraine’s grain exports should not be allowed to continue. The collective West needs to open Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, primarily the major ports in Odesa, to mitigate the ongoing crisis in countries suffering from food insecurity, as well as enabling Ukraine to sell the twenty-eight million tons of grain it has in storage.

Ukraine is a global granary

Before communism, Ukraine was the granary of the world; since the privatization of agricultural land in 2000, it has become so again. Its grain production has skyrocketed, and Ukraine is now focusing on modern grains—corn, wheat, soy, canola, and sunflower oil.

Ukraine is a major producer of many grains. In 2021, it produced some eighty-six million tons of grain. The latest reliable statistics are for 2019 from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. In 2019, Ukraine produced 35.9 million tons of corn. It was the fifth-biggest grower of corn after the United States, China, Brazil, and Argentina, producing 3.1 percent of all corn in the world. Ukraine produced 28.4 million tons of wheat, or 3.7 percent of global production, ranking seventh in the world, after China, India, Russia, the United States, France, and Canada.

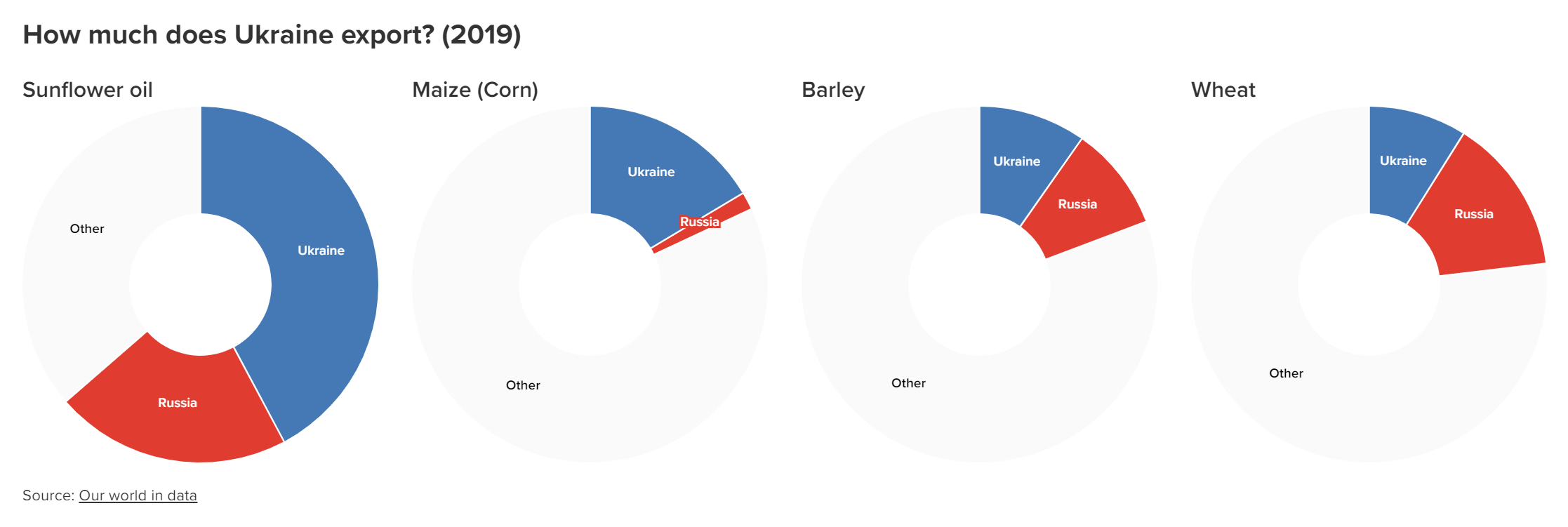

Ukraine’s role as an exporter of grain is much greater, because most of the other major producers are very large countries, such as China, India, the United States, Indonesia, and Brazil, which consume much of their produce themselves. In 2019, 42 percent of all global sunflower-oil exports came from Ukraine, as did 16 percent of all corn exports, 8.9 percent of all wheat exports, and 9.7 percent of all barley exports. Because of Ukraine’s swiftly expanding agriculture, the country’s role as a grain exporter has risen fast.

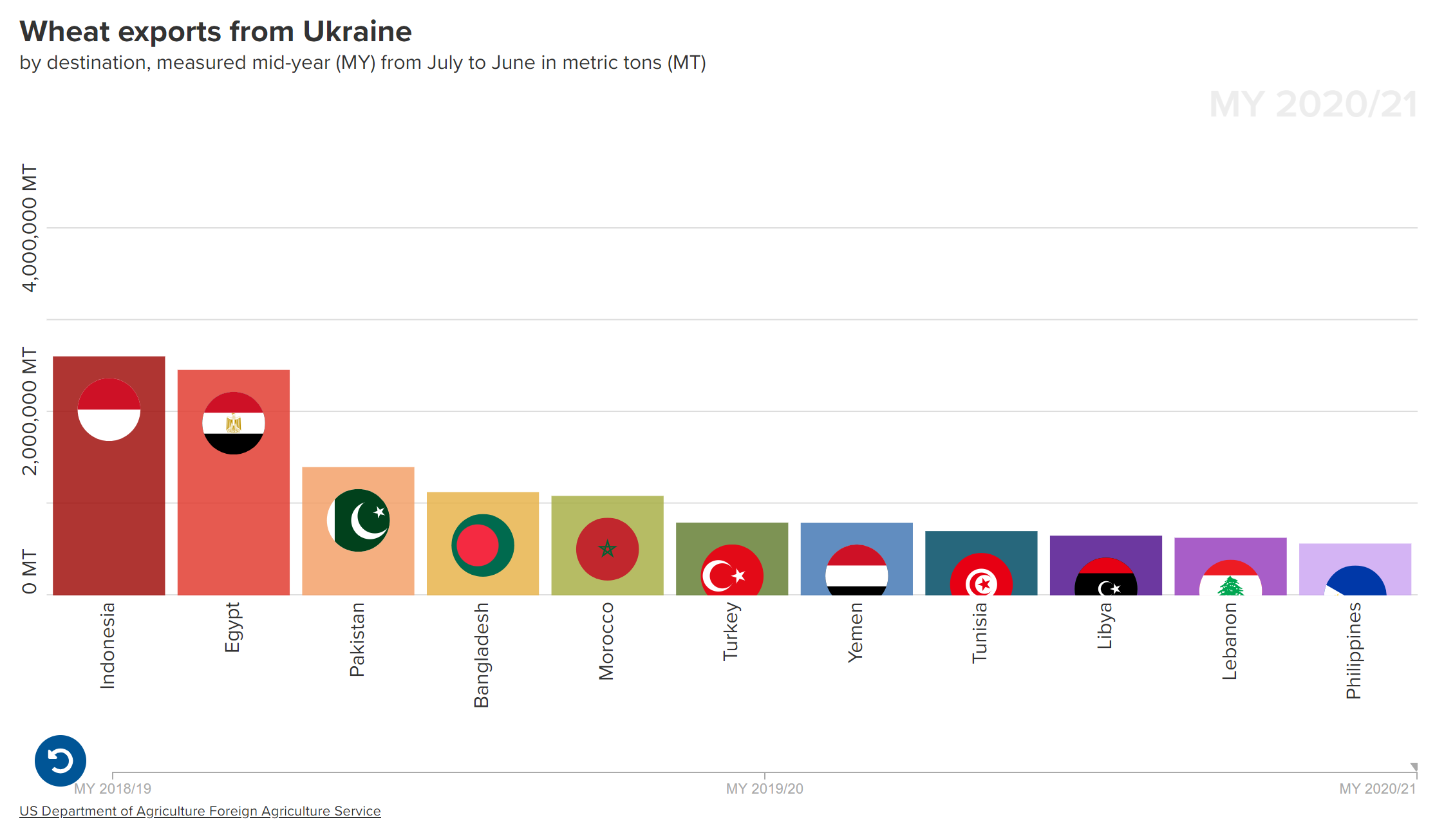

Most attention is being devoted to wheat because it is crucial for economically developing countries’ supplies of bread, a basic staple. With its steadily improving agriculture, Ukraine’s exports have risen in turn. For the year until July 2021, the US Department of Agriculture assessed Ukrainian exports of wheat at 23.5 million tons. These wheat exports were spread to many countries in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. The main recipients by quantity were Indonesia, Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Morocco, Turkey, Yemen, Tunisia, Libya, Lebanon, and the Philippines. These countries are most likely to suffer from a new shortfall of wheat.

Corn is the second important grain export. Ukraine has nearly perfect conditions for growing corn, similar to those of the US states of Iowa and Illinois, and corn production has grown exponentially. For the year until July 2021, the US Department of Agriculture assessed Ukrainian exports of corn at thirty-four million tons. The corn exports went in quite different directions from the wheat exports, going to somewhat wealthier countries, because corn is mainly used for animal feed. In recent years, Ukraine’s main market has been China, which bought no less than 8.4 million tons of Ukraine’s corn exports in 2020–2021. Other major purchasers were Spain, the Netherlands, Egypt, and Iran.

Officially, Russia closed vast expanses of the Black and the Azov Seas for civilian maritime traffic, under the pretext of naval exercises, for the period from February 13–19. It had no legal basis for this decision. Thus, Russia closed the access to all Ukraine’s ports from the Black Sea, and the ports have remained shut ever since. Russia has also mined them. Russian naval ships have hit at least ten commercial ships since Russia launched its assault, according to the International Maritime Organization. They sank one Estonian commercial ship. About eighty commercial ships have been caught in the Black Sea or the Sea of Azov for months. The risk to commercial shipping in the area has soared, and the cost of marine insurance in the Black Sea has skyrocketed as a result. […]

Accusations of Russian destruction and plunder

The Kremlin has by no means ignored the global food crisis. To the contrary, it has decided to aggravate and exploit it. Ample Ukrainian sources report that the Russian military has intentionally bombed and burnt Ukrainian grain elevators, fertilizer stores, farming areas, and infrastructure.

Russians have stolen grain on an industrial scale. Ukraine’s Deputy Agriculture Minister Taras Vysotskiy stated in early May that Russians had exported 441,000 tons of grain from the four occupied regions of Zaporizhia, Kherson, Donetsk, and Luhansk. They transported the stolen grain on trucks to Novorossiisk, the main Russian port on the Black Sea, or Sevastopol, the top Crimean port. Then, they ship the grain through the Bosporus to Mediterranean ports. Ports in Cyprus and Lebanon have reportedly turned down delivery of stolen grain, while Russia’s ally Syria accepts it. However, Vysotskiy states that only 1.5 million tons of grain was stored on newly occupied territory.

Putin has a long history of personal involvement in major graft operations and is reportedly micromanaging elements of the war on Ukraine. Businessman and human-rights leader Bill Browder showed how such business is done in his investigation of the Sergei Magnitsky affair. Of the $230 million stolen from the Russian tax office, the Panama Papers showed that $800,000 had gone to President Putin himself, and Putin fought tooth and nail to defend the theft from his own government. Given Putin’s history and the big business of stealing and selling Ukraine’s grain, it is likely that these new operations are being organized at the highest level.

Similarly, since 2014, Russian government-supported business has exported coal from illegally confiscated coal mines in occupied Donbas to Russia, Belarus, Poland, and Turkey, leading to legal cases in Poland and Turkey. This is part of the Putin government’s close cooperation with organized crime, which has been deeply detailed in recent books by Karen Dawisha, Bill Browder, Catherine Belton, and this author. [more]

One Response

Comments are closed.