Gas flaring soars in Mexico, derailing its climate change pledges as it seeks to boost oil output – “It’s like hell”

By Stefanie Eschenbacher

23 February 2022

(Reuters) – It never gets completely dark in Colonia El Carmen, home to Mexico’s largest natural gas processing center, in the poor southern state of Chiapas.

After sunset, a red glare emanates from flares dotted around the Cactus gas processing center, run by state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

The complex is unable to process the vast volume of gas emitted as a byproduct of oil production and disposes of the excess by flaring it, a widespread industry practice that scientists said is detrimental to the environment.

Burning the excess gas is cheaper than investing in infrastructure to capture, process and transport it for other uses. But in addition to carbon dioxide, flaring releases methane, a more potent greenhouse gas.

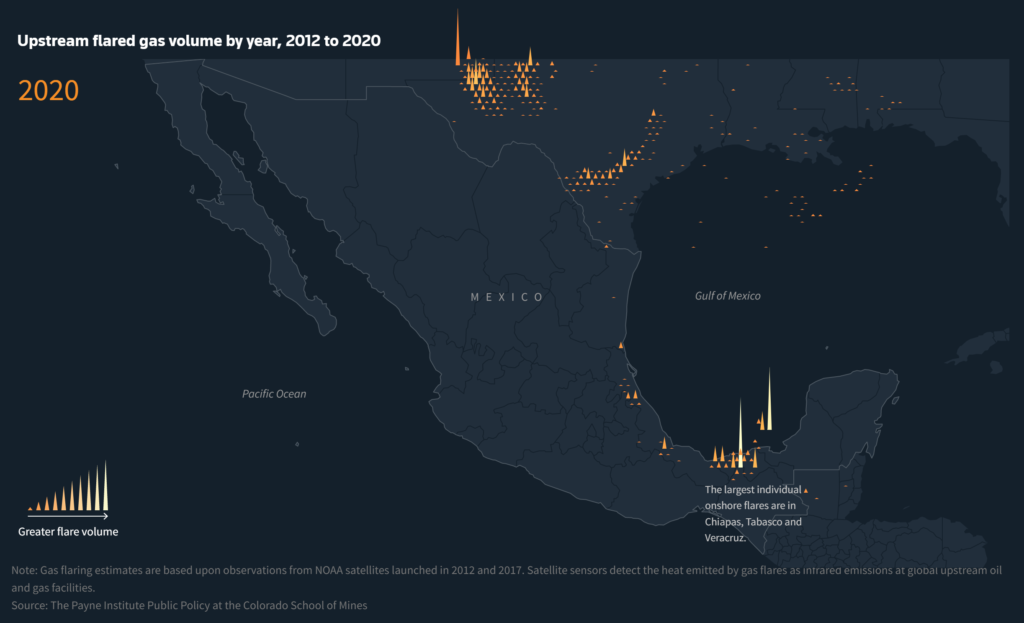

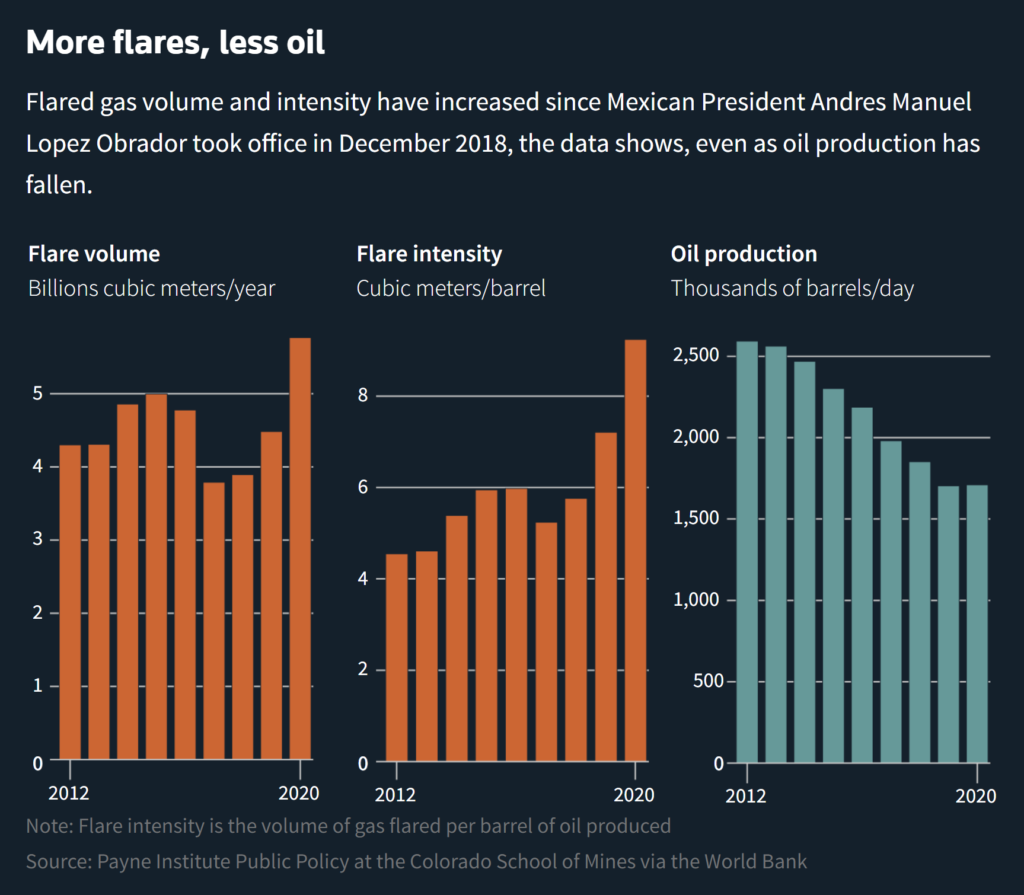

NASA satellite images of flare sites across Mexico, analyzed for Reuters by scientists at the Earth Observation Group of the Colorado School of Mines, showed that gas flaring has dramatically increased under Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

The volume of gas flared leapt by 50% from 3.9 billion cubic meters (bcm) when Lopez Obrador took office in 2018 to 5.8 bcm in 2020, the data showed, putting Mexico among the world’s top 10 flarers.

And preliminary data collected for the first 10 months of 2021 suggest Mexico is on track to break 2020’s record of flaring activity, the Colorado School of Mines team found, with February registering an all-time monthly high.

The new data suggests that in spite of signing an international pledge to reduce methane emissions, Mexico is moving in the opposite direction from a global push to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas production.

Pemex declined to comment. Mexico’s presidency, energy and environmental ministries, and environmental regulator did not respond to repeated requests for comment on this report.

Mexico is among 34 countries – as well as 51 oil companies – that have signed a World Bank-backed pledge to cut routine flaring to zero by 2030.

“There’s been a significant increase in both the number of individual flare sites and the volume of gas that is being flared in Mexico,” said Christopher Elvidge, the principal investigator of the Colorado School of Mines team.

The satellite data is the only daily global survey that collects information on the temperature, location and size of gas flares from the oil industry.

The 2021 preliminary data has not previously been reported and the analysis of the 2020 figures provided the first detailed picture of where flaring is taking place in Mexico.

This data showed that Chiapas and the neighboring states of Tabasco and Veracruz are the epicenter of a dramatic rise in gas flaring, close to several population centers. […]

Residents’ ‘Hell’

Residents of Colonia del Carmen – home to roughly 4,000 – listed six major environmental incidents linked to flaring since July 2021 in an official complaint to Pemex, stamped as received on 30 September 2021. Residents said they are awaiting Pemex’s reply.

Photographs in the complaint showed oil residue in a lagoon used for fishing, on streets and cars. Residents cited several flares so large they caused “panic” and heat so intense it led to the cancellation of an open air cinema for children.

Residents said in 15 separate interviews that they have suffered from headaches or coughing, and children complained of irritated eyes and itching skin.

Others pointed to a strong, lingering sulfur-like smell, ash rains, and contaminated soil.

“It’s like hell,” said Orbilio Garcia, whose family land was expropriated by the government to expand Pemex operations, but still lives nearby. “When our son was born, we got so concerned about his health that we moved a little further away. But we don’t have enough to leave the area and start over elsewhere.” […]

‘Highly insufficient’ policies

The lack of investment and maintenance is worsening the flaring as Lopez Obrador instead prioritizes exploration and production activities, five regulatory sources and two Pemex petroleum geologists told Reuters.

To meet Mexico’s international emission targets, the president is pinning his hopes on greater use of hydroelectric power and reforestation.

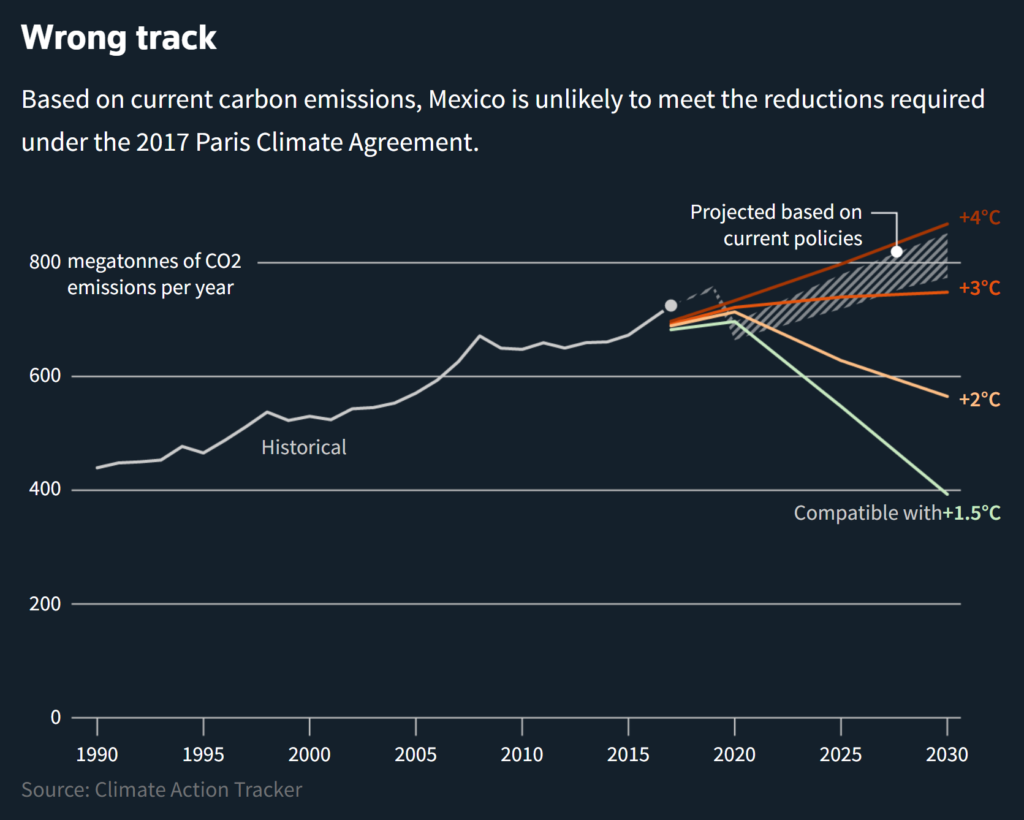

Climate Action Tracker, a site run by independent scientists, rates Mexico’s policies to be “highly insufficient” in meeting a goal of holding global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius – let alone the stricter target of 1.5 degrees agreed at a U.N. climate conference in Paris in 2015.

Lopez Obrador’s policies will lead to rising – rather than falling – emissions, it concluded.

The two Pemex geologists with access to reserves data, who asked not to be identified because the information is sensitive, said the challenges to reduce flaring are only going to get greater. [more]