In southern France, drought, rising seas threaten traditions – “The sea level rises on our coast and takes more and more of our land”

By Daniel Cole

30 October 2022

SAINTES-MARIE DE LA MER, France (AP) – In a makeshift arena in the French coastal village Aigues-Mortes, young men in dazzling collared shirts come face-to-face with a raging bull. Surrounded by the city’s medieval walls, the men dodge and duck the animal’s charges while spectators let out collective gasps. Part ritual and part spectacle, the tradition is deeply woven into the culture of the country’s southern wetlands, known as the Camargue.

For centuries people from across the region have observed Camarguaise bull festivities in the Rhone delta, where the Rhone river and the Mediterranean Sea meet. But now the tradition is under threat by rising sea levels, heat waves and droughts which are making water sources salty and lands infertile. At the same time, there are efforts by authorities to preserve more land, leaving less for bulls to graze.

“Here in Camargue the bull is God, like a king,” said Aigues-Mortes resident Jean-Pierre Grimaldi as he cheered on from the private arena stands, where he’s watched competitions for decades. “We live to serve these animals … some of the most brilliant bulls even have their own tombs built for them to be buried in.”

Generations of “manadiers,” or ranchers, like Frederic Raynaud, have dedicated their lives to raising the bulls that are indigenous to the region. Wilder bulls that can win prestigious fighting events are the most prized.

Raynaud, a fifth-generation manadier, has raised many such bulls on his “manade” — a term for ranches in the region — just east of Aigues-Mortes. His ranch currently looks after around 250 Camargue bulls and 15 horses that graze in semi-wild pastures along the coast. He fears that soon his much-celebrated cattle will not have lands to feed on.

“The sea level rises on our coast and takes more and more of our land,” Raynaud said.

A temporary dike constructed by local authorities to stop the growing sea has sunk in on itself, the water passing right through it and into the manade’s pastures. The edge of the ranch is slipping into the sea. Land that hasn’t been swallowed up is becoming unusable as encroaching waters make the wetlands more and more salty. Heat waves and drought, exacerbated by climate change, are also depriving the land of fresh water, allowing sea water to take over.

“We used to have the salt rising up on just on our land” nearer the coast, Raynaud said. “But now the salt rises up through the soil five or six kilometers (3 to 4 miles) beyond the shoreline where you can see salt encrusting over the vegetation.”

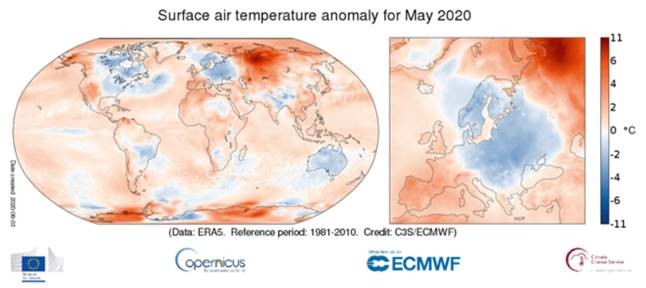

The sea level around the town of Saintes-Marie de la Mer in Camargue has risen by a steady 3.7 millimeters (0.15 inches) per year from 2001 to 2019, almost twice the global average sea level rise measured throughout the 20th century, according to the local Tour du Valat research institute. Warming, expanding oceans and the melting of ice over land, both a result of climate change, are contributing to higher sea levels.

Researchers added that the advance of salt into the soil would leave the land barren and uninhabitable long before the sea engulfs it. Some affected pastures have already become bare with little vegetation and the abnormally high salt content poses health risks to organisms not able to tolerate it. …

The Rhone river has long served as the Camargue’s lifeline, bringing fresh water from the Alps and dampening salt levels in the Camargue. As rain and snowfall decrease, it’s becoming a less reliable fresh water source, with researchers estimating the river’s flow has reduced by 30% in the last 50 years and is expected to only worsen.

“Glaciers which are in the process of melting at an incredibly high rate have already passed the point of no return, so probably in the years to come, the 40% of river flow that arrives in Camarague will be reduced to a much smaller percentage,” said Jean Jalbert of Tour du Valat.

During summers plagued by high temperatures and diminished rainfall, the sea water can reach up to 20 kilometers (12 miles) into the Rhone River. During a heat wave in August this year, the Raynaud family’s water pump in the Petite Rhone, an offshoot of the main river, began pumping salt water. They were forced to move the pump farther up the river outside the perimeters of their own ranch to irrigate their land and feed their animals. [more]

In southern France, drought, rising seas threaten traditions