Why are Alaska’s rivers turning orange? “It was a famous, pristine river ecosystem, and it feels like it’s completely collapsing now”

By Alec Luhn

24 December 2023

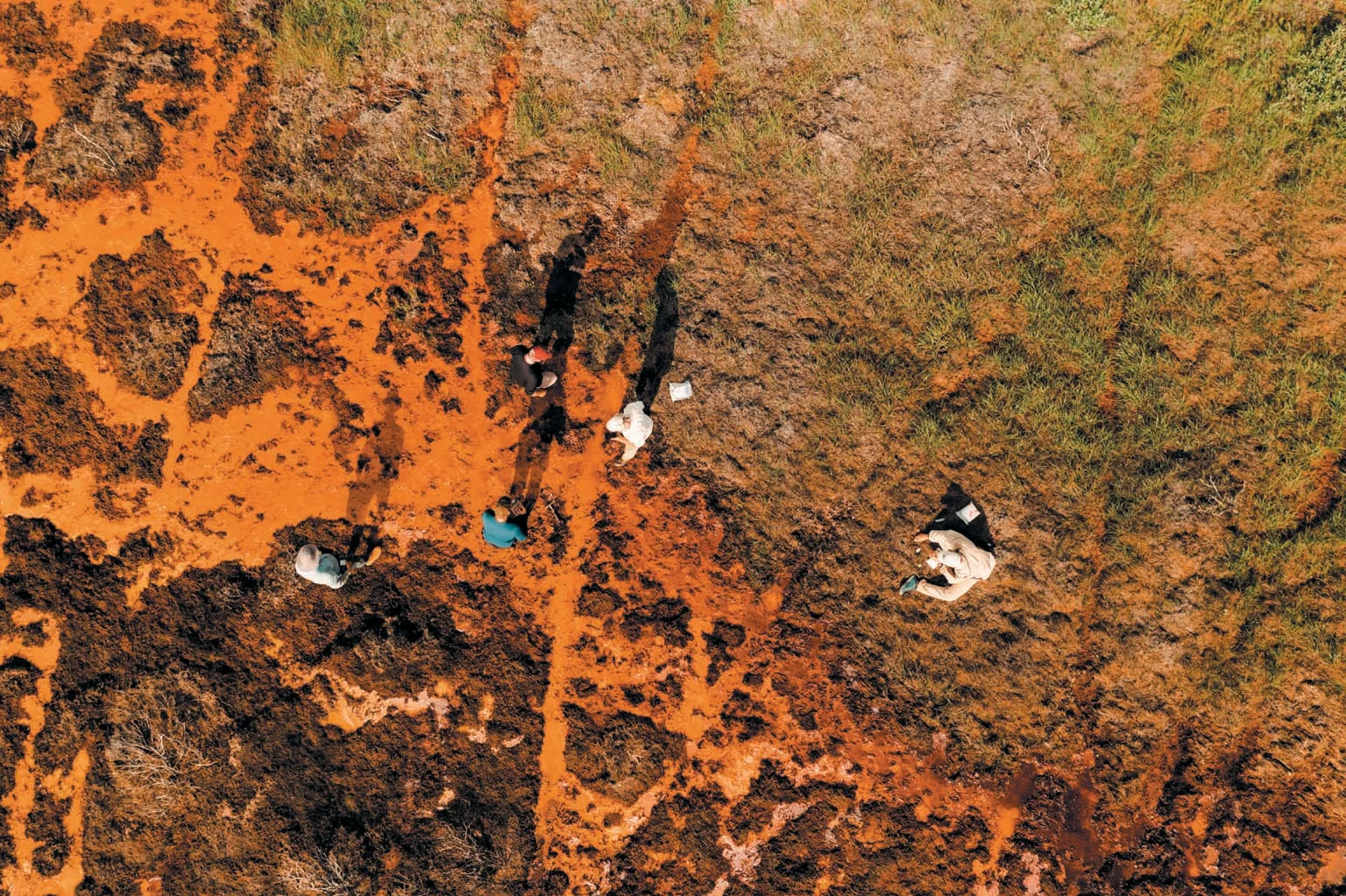

(Scientific American) – It was a cloudy July afternoon in Alaska’s Kobuk Valley National Park, part of the biggest stretch of protected wilderness in the U.S. We were 95 kilometers (60 miles) from the nearest village and 400 kilometers from the road system. Nature doesn’t get any more unspoiled. But the stream flowing past our feet looked polluted. The streambed was orange, as if the rocks had been stained with carrot juice. The surface glistened with a gasolinelike rainbow sheen. “This is bad stuff,” said Patrick Sullivan, an ecologist at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

Sullivan, a short, bearded man with a Glock pistol strapped to his chest for protection against Grizzly Bears, was looking at the screen of a sensor he had dipped into the water. He read measurements from the screen to Roman Dial, a biology and mathematics professor at Alaska Pacific University. Dissolved oxygen was extremely low, and the pH was 6.4, about 100 times more acidic than the somewhat alkaline river into which the stream was flowing. The electrical conductivity, an indicator of dissolved metals or minerals, was closer to that of industrial wastewater than the average mountain stream. “Don’t drink this water,” Sullivan said.

Less than a dozen meters away the stream flowed into the Salmon River, a ribbon of swift channels and shimmering rapids that winds south from the snow-dimpled dun peaks of the Brooks Range. This is the last frontier in the state known as “the last frontier,” a 1,000-kilometer line of pyramidlike slopes that wall off the northern portion of Alaska from the gray, wind-raked Arctic Coast.

One of the most remote and undisturbed rivers in America, the Salmon has long been renowned for its unspoiled nature. When author John McPhee paddled the Salmon in 1975, it contained “the clearest, purest water I have ever seen flowing over rocks,” he wrote in Coming into the Country, an Alaska classic. A landmark 1980 conservation act designated it a wild and scenic river for what the government called “water of exceptional clarity,” deep, luminescent blue-green pools and “large runs of chum and pink salmon.”

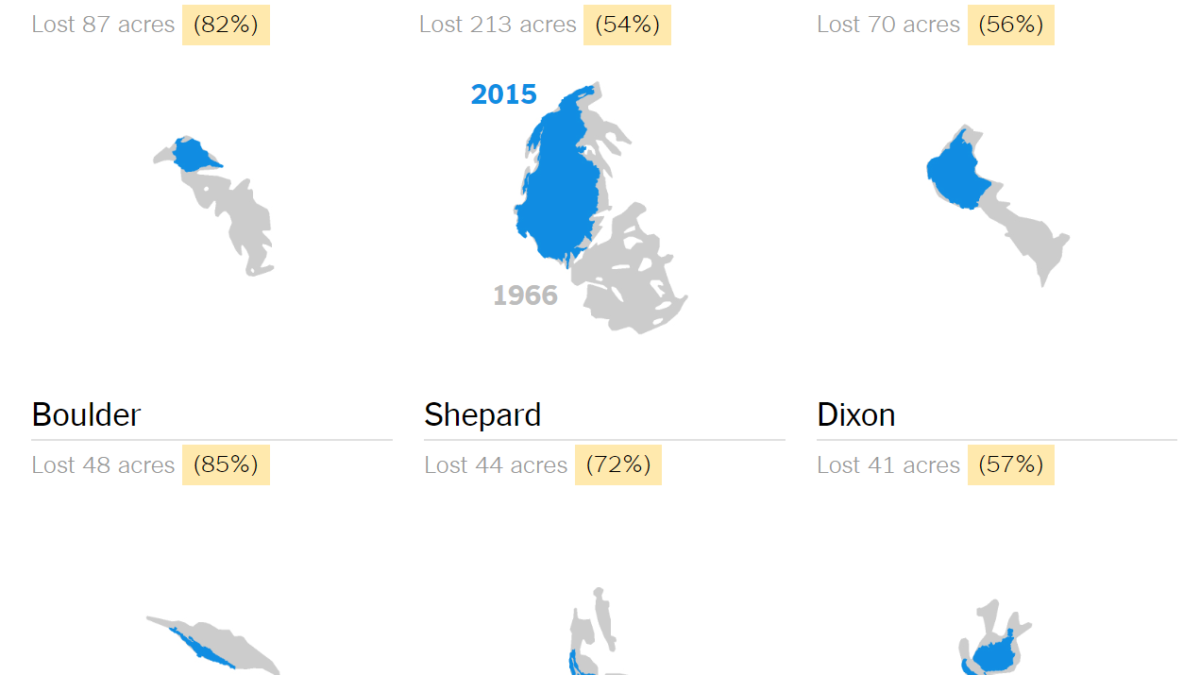

Now, however, the Salmon is quite literally rusting. Tributary streams along one third of the 110-kilometer river are full of oxidized iron minerals and, in many cases, acid. “It was a famous, pristine river ecosystem,” Sullivan said, “and it feels like it’s completely collapsing now.” The same thing is happening to rivers and streams throughout the Brooks Range—at least 75 of them in the past five to 10 years—and probably in Russia and Canada as well. This past summer a researcher spotted two orange streams while flying from British Columbia to the Northwest Territories. “Almost certainly it is happening in other parts of the Arctic,” said Timothy Lyons, a geochemist at the University of California, Riverside, who’s been working with Dial and Sullivan.

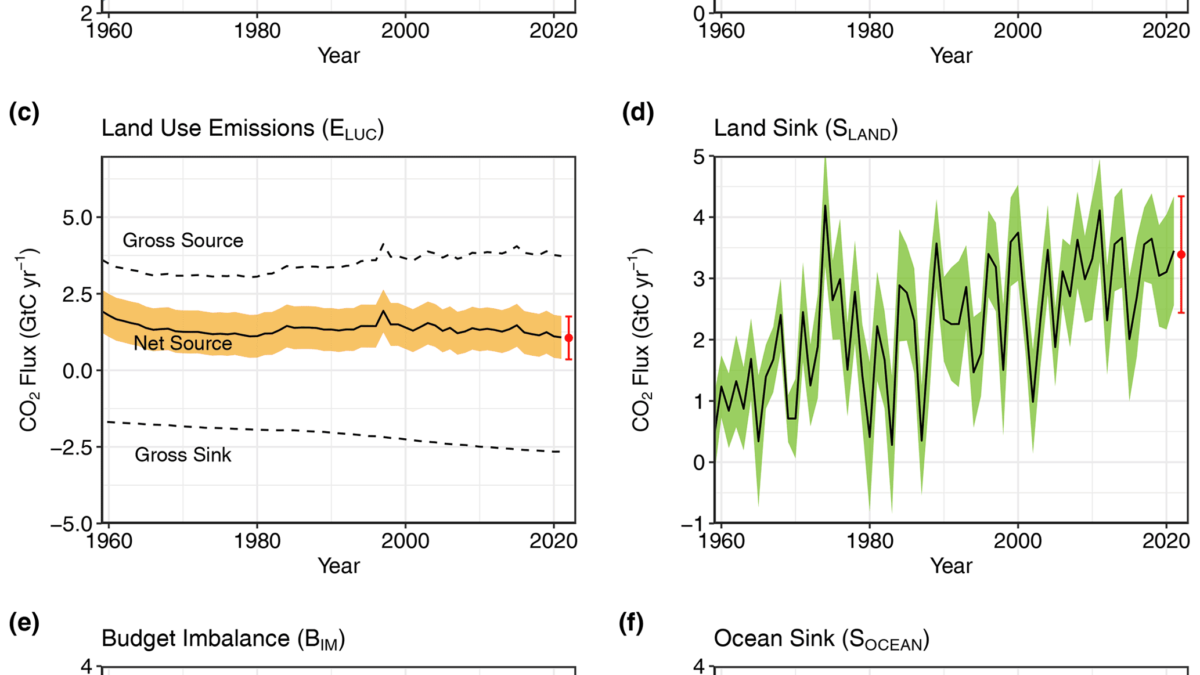

Scientists who have studied these rusting rivers agree that the ultimate cause is climate change. Kobuk Valley National Park has warmed by 2.4 degrees Celsius (4.32 degrees Fahrenheit) since 2006 and could get another 10.2 degrees C hotter by 2100, a greater increase than projected for any other national park. The heat may already have begun to thaw 40 percent of the park’s permafrost, the layer of earth just under the topsoil that normally remains frozen year-round. McPhee wanted to protect the Salmon River because humans had “not yet begun to change it.” Now, less than 50 years later, we have done just that. The last great wilderness in America, which by law is supposed to be “untrammeled by man,” is being trammeled from afar by our global emissions.

But how, exactly, permafrost thaw is turning these rivers orange has been a mystery. Solving it is crucial for understanding what the sweeping ecological impact could be and to help communities adapt, such as the eight Alaska Native villages that depend on rivers in the western Brooks Range for fish and drinking water. Some researchers think acid from minerals is leaching iron out of bedrock that has been exposed to water for the first time in millennia. Others think bacteria are mobilizing iron from the soil in thawing wetlands. […]

The first investigators to document the rusting rivers were U.S. Geological Survey and National Park Service personnel studying how permafrost changes in the Brooks Range are affecting fish such as the Dolly Varden, a big, silvery green char with red spots that local villages prize above all others. In August 2018, when biologist Mike Carey flew by helicopter to retrieve a water sensor he had left in a clean stream east of the Salmon, he saw that the bottom was blanketed in orange slime. He couldn’t find any fish or insects. “Biodiversity just crashed,” he recalled.

Carey thought the weird situation was a one-off until the following July, Alaska’s hottest month on record. The Agashashok River, 96 kilometers west of the Salmon, turned from turquoise to orange-brown along part of its course. In the winter of 2019 the snowpack was abnormally high; that can insulate the ground, further encouraging permafrost thaw. Then came another hot summer and another snowy winter, and the rusting spread. [more]