Glacier National Park’s name will outlive its glaciers – “It’s just kind of sad to see”

By Doug Struck

18 June 2019

GLACIER NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA (The Christian Science Monitor) – Maria Clemens took time off from her post-college summer job on a Montana ranch to hike into this national park to see a glacier. “I don’t like it,” she pronounced on the trail as she returned. “It’s just kind of sad to see.”

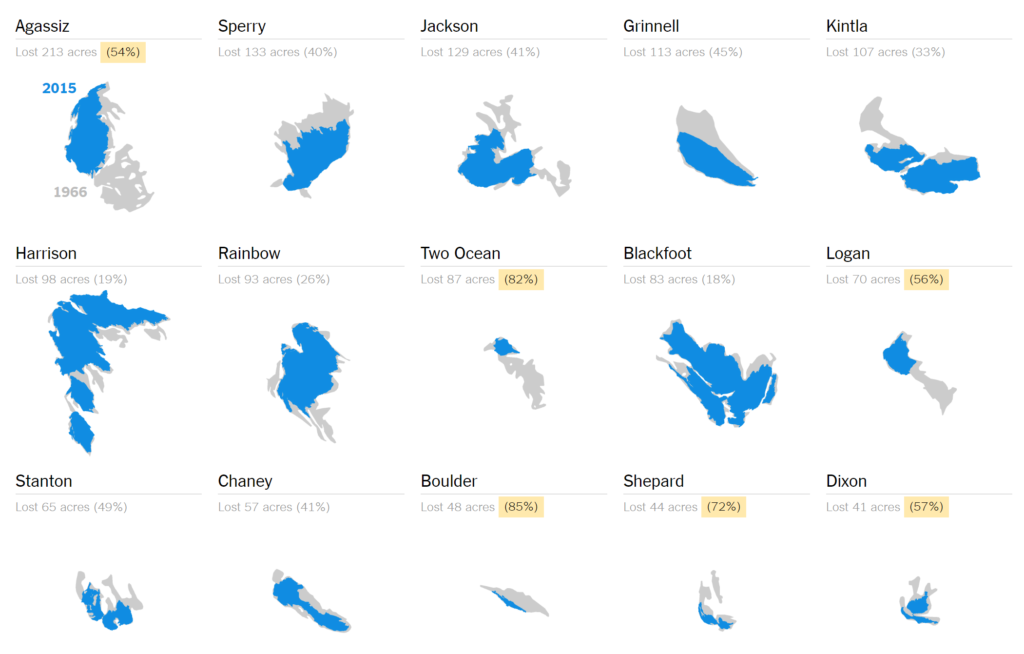

Her displeasure is over the ever-shrinking glaciers that gave this park its name. There were about 150 of them in 1850, now there are about 25, and they are projected to be gone before Ms. Clemens reaches her 40s.

The looming ice rivers have been ravaged by the changing climate. Glaciologists have penciled in 2030 for the glaciers’ obituary, though some ice may linger a bit. As the last surviving glaciers shrivel into shaded folds of the mountains, snow whipping over the Continental Divide may give them “a little lease on life just at the very end,” says Dan Fagre, a glacier expert at the United States Geological Survey. But, he says, “it won’t change the ultimate prognosis.”

What, then, is the future of a million-acre national park that draws 3 million visitors each year when its marquee lure is gone?

Officially, of course, the park will carry on.“Ninety percent of visitors won’t notice a difference,“ predicts the park superintendent, Jeff Mow. “There will always be white and snow on the mountains in Glacier. It’s just how much of that is actually a glacier.” […]

A small surge of visitors is coming to pay last respects to the cold colossi that once ruled and shaped the Earth. And they are ready to lay blame for the glaciers’ fate.

“We should do a better job of protecting this Earth,” says Britney Herbert, who came from Los Angeles to see the glaciers because “we should see them before they go.”

“It’s surreal,” adds her hiking companion, Patrick Yarbrough, as a cloud tumbled over the mountains and spattered the trail with drops. “We take the land so much for granted.”

Above them, three glaciers – Grinnell, Salamander, and Gem – seemed weary with age, and slumped toward the valley. Their threadbare skirts of ice were tattered, revealing the hard black mountain underneath. [more]