How an atmospheric river hit Sydney – “We’re seeing these events which we call one-in-1000 year events or one-in-100 year events now becoming one-in-one year events”

By Ben Cubby, Laura Chung, and Nigel Gladstone

8 July 2022

(The Sydney Morning Herald) – Every disaster movie starts with a scientist being ignored, so the saying goes. In the Hollywood version, the lone researcher stares at a screen, eyes widening as the ominous data comes through, and leaps for a phone to try to alert the world.

The flood disaster that enveloped large swaths of the state this week showed that the same patterns play out in real life, albeit in the more gradual, mundane form of council hydrological studies and government reports. There is a vast body of evidence, ranging from the accounts of Indigenous Australians and early colonists right up to present-day scientific journals, showing that in the conditions we have seen this week, the great curves of the Nepean and Hawkesbury rivers would flood. We have been repeatedly warned.

“I get frustrated with the way the can is kicked down the road,” said Ian Wright, a water expert at the School of Science at Western Sydney University. “This really has happened again and again. But the new suburbs, the infrastructure, keep going up on the floodplain.”

One of those suburbs is Shanes Park, which straddles Penrith and Blacktown about 50 kilometres west of the Sydney CBD. Suzette Turner was scraping the mud out of her property there this week – the fourth time her extended family has been forced from home by floods in two years.

“How many times do we have to go through this?” Turner said. “It is heartbreaking to put stuff in the back of a ute and on the side of the road. We were financially wiped out last time, we were still recovering and building until a few days ago – we were still in recovery mode. You get on top of things, but then get wiped out again, how much more can people take?”

Turner said her heart broke when she opened the door to her mother’s flat at the back of their property, and found the memories of 85 years – family photos, horse-riding trophies, and wooden furniture that had been there for generations – mud-soaked and destroyed.

“I don’t have the heart to bring her back,” Turner said. “I don’t have the words, it’s heartbreaking to see her whole life – just in piles of flood and rubbish, again.

“It is hard to be positive, it’s hard not to be dragged down, it’s hard to get up and fight every day and there are little kids watching you,” she told the Herald. “It is hard. You cry after they have gone to bed, you cry in the bathroom, and then you put a happy face on and walk out.”

“We are all in the same boat, we’ve got nothing together. We will [clean] this house and then the next house and then the next house.”

What hit the city and much of the state’s east coast this week has been described as an “atmospheric river” – a concentrated ribbon of water vapour moving about a kilometre above the Earth’s surface. Usually, these rivers of the sky bring beneficial rainfall to agricultural areas, but if they hit a nasty cold front, they can be quickly forced higher into the atmosphere where vapour condenses and falls as torrential rain.

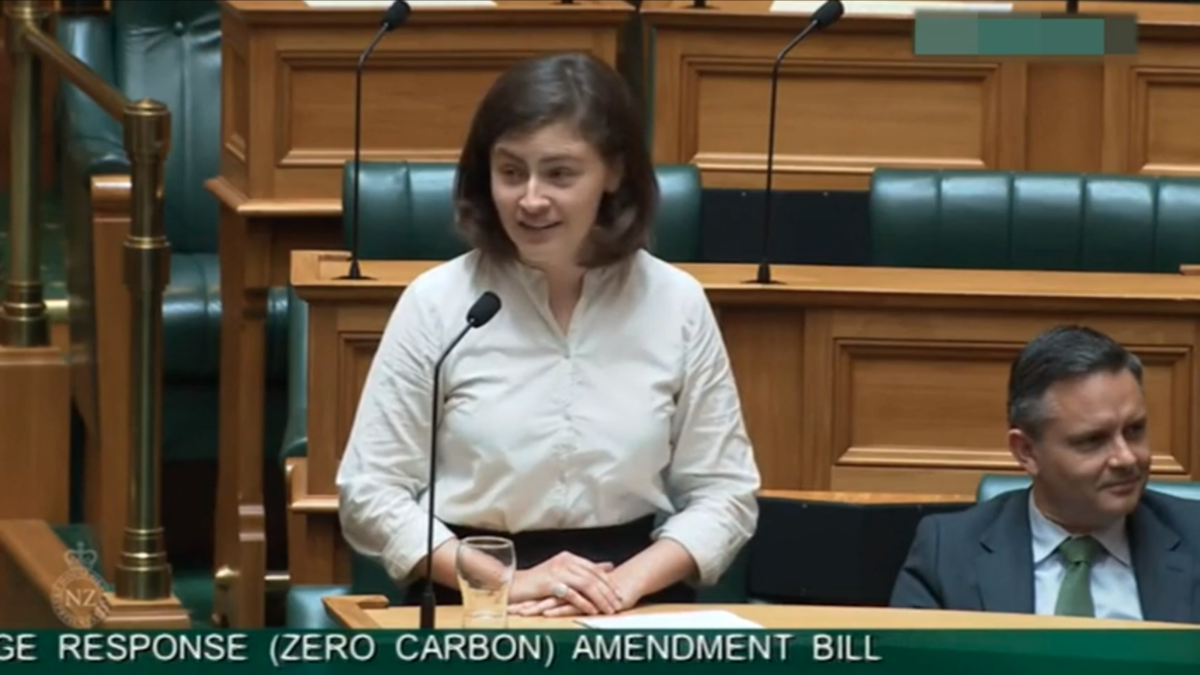

“When this river interacted with the low-pressure system off the east coast, the water vapour was converted from a gas to a liquid,” said Kimberley Reid, an atmospheric scientist from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes at Monash University.

The effect on the ground was shattering. Camden in Sydney’s south-west, had over 15 centimetres of rain in one day. Parts of the Illawarra had an astonishing 35 centimetres.

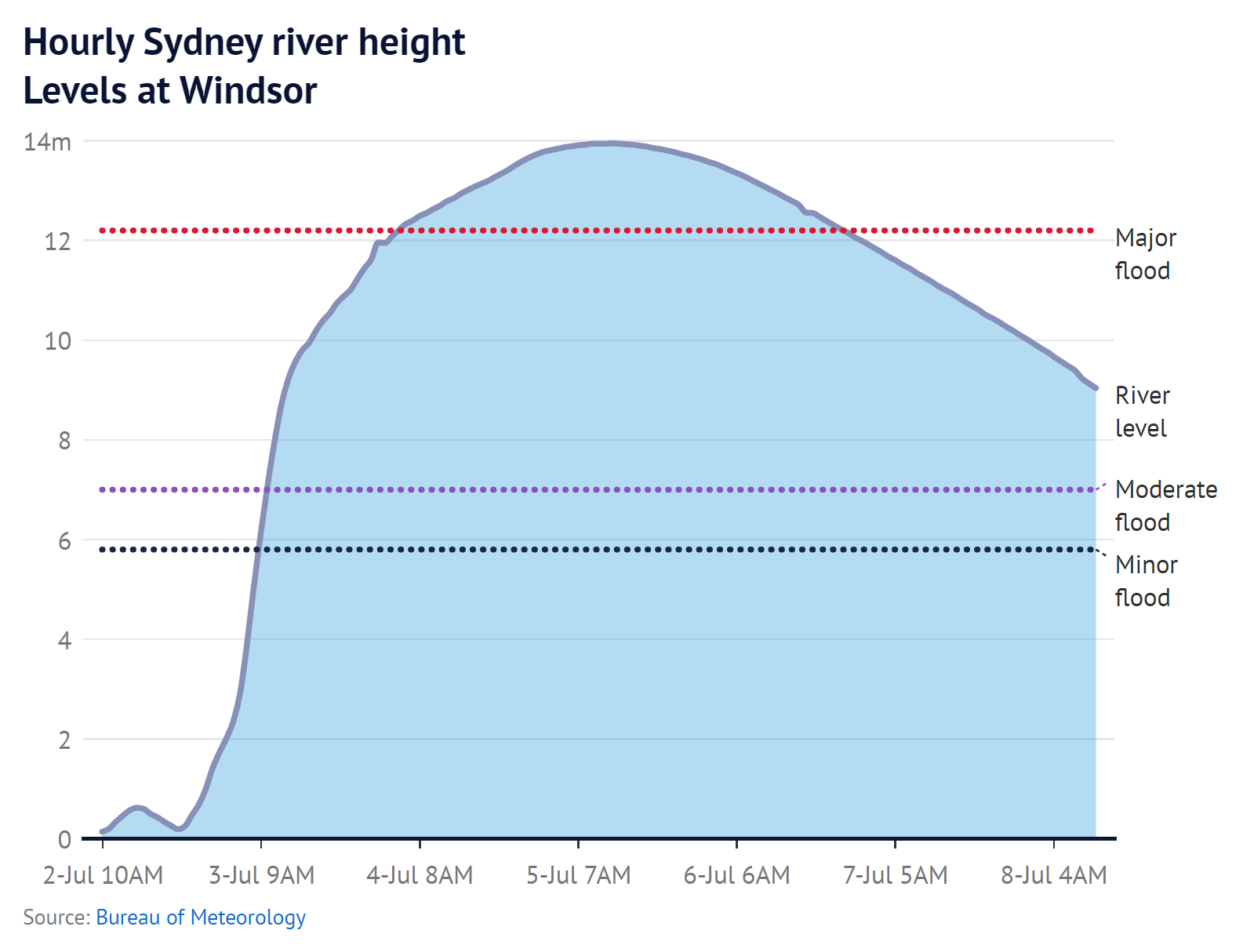

The warnings were timely: the Bureau of Meteorology had been watching the low-pressure system develop. On Wednesday, June 29, it flashed out its first warning of heavy rainfall for the weekend of July 2-3, and the update was rapidly circulated to emergency agencies, and to the general public via the media. The first flood watch was issued by the bureau on Thursday, June 30.

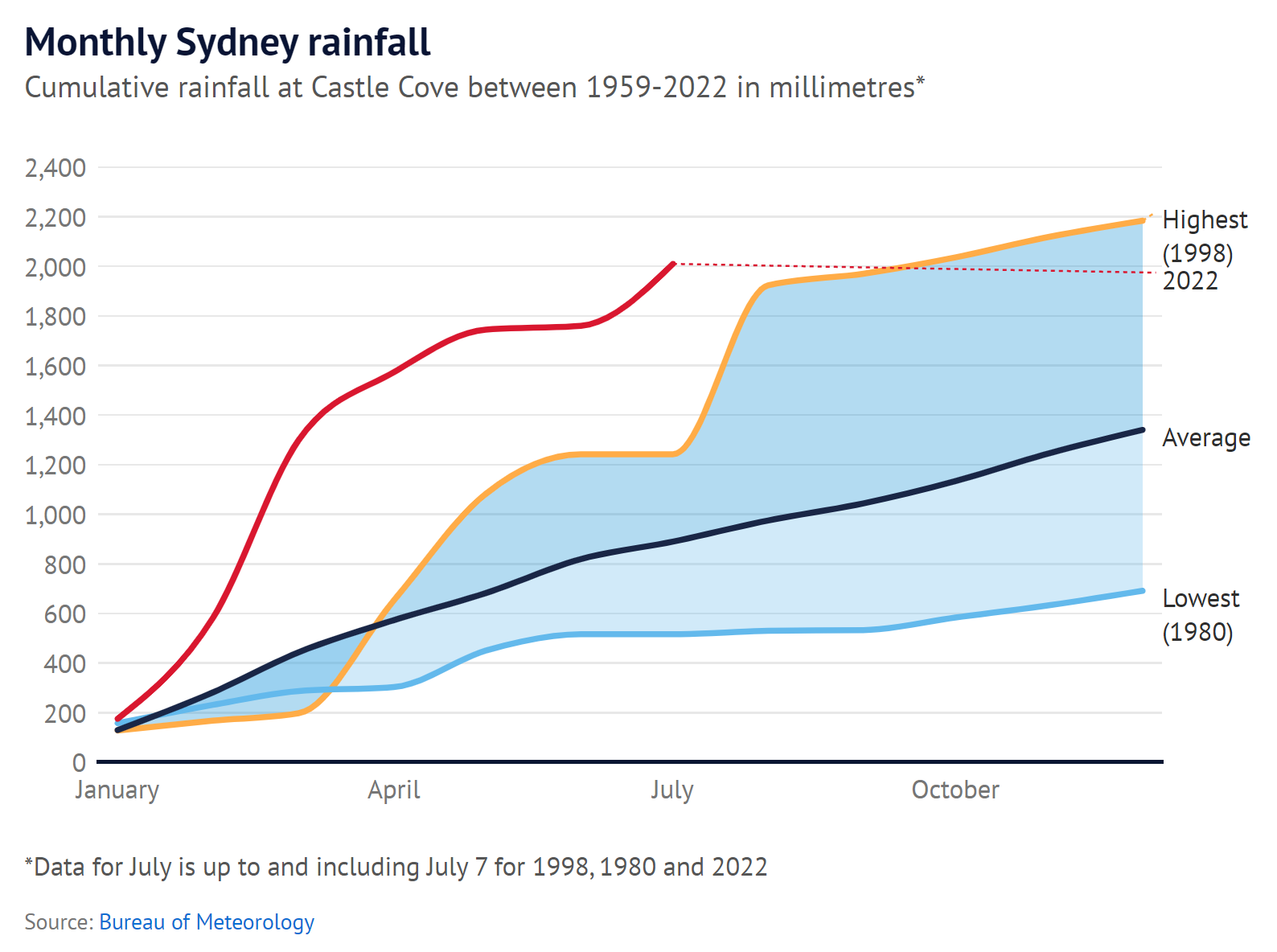

Soon, dozens of local rainfall records were being smashed. In the first week of the month, it is already Sydney’s eighth-wettest July in over a century of records – with three weeks still to come. Around the state, more than 85,000 people were displaced from their homes or warned they may have to leave. Many are yet to return.

It wasn’t just the intensity of the cloudburst that caused so much damage, but the fact that it fell on ground already thoroughly saturated after months of unseasonably heavy rainfall. The double-dip La Nina that has kept much of eastern Australia drenched for the past two years ensured that there was nowhere for the water to go but into rivers that then spilled out onto land.

Human-induced climate change is already playing its part in making these weather patterns more intense, Reid says, but her research suggests much more is to come. In a study of the downpour that caused major floods in Sydney in March 2021, Reid found that similar rain events would be 80 per cent more likely in coming decades.

“We looked at the high emissions scenarios, with business-as-usual leading to a four-degree temperature rise by the end of the century, and scenarios where there was just a two-degree temperature rise, and we’re seeing a very similar rise in probability for these events – about 80 per cent,” Reid said.

So massive rainfall events for Sydney look set to increase at a high rate this century, even if the world slows down the pace of climate change with significant cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, Reid’s world-first study suggests. […]

This seems to have been accepted by the NSW premier, Dominic Perrottet, who said in relation to the floods this week that the impacts of climate change had made some current planning redundant.

“We’re seeing these events which we call one-in-1000 year events or one-in-100 year events now becoming one-in-one year events,” Perrottet said. [more]

‘How many times do we have to go through this?’ How an atmospheric river hit Sydney