Sri Lanka is the first domino to fall in the face of a global debt crisis – Will Bangladesh be next? – “I’m deeply concerned about developing countries”

By Larry Elliott

9 May 2022

(The Guardian) – The departure of Sri Lanka’s prime minister, Mahinda Rajapaksa, follows weeks of protest and a deepening crisis. There is no bankruptcy system for states but if there was then the south Asian country – down to its last $50m (£40m) of reserves – would be first in line to use it.

A team from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) this week started work with officials in Colombo over a bailout that will include a tough package of reforms as well as financial support. But as the IMF and its sister organisation, the World Bank, know full well, this is about more than the mismanagement of an individual country. They fear Sri Lanka is the canary in the coalmine.

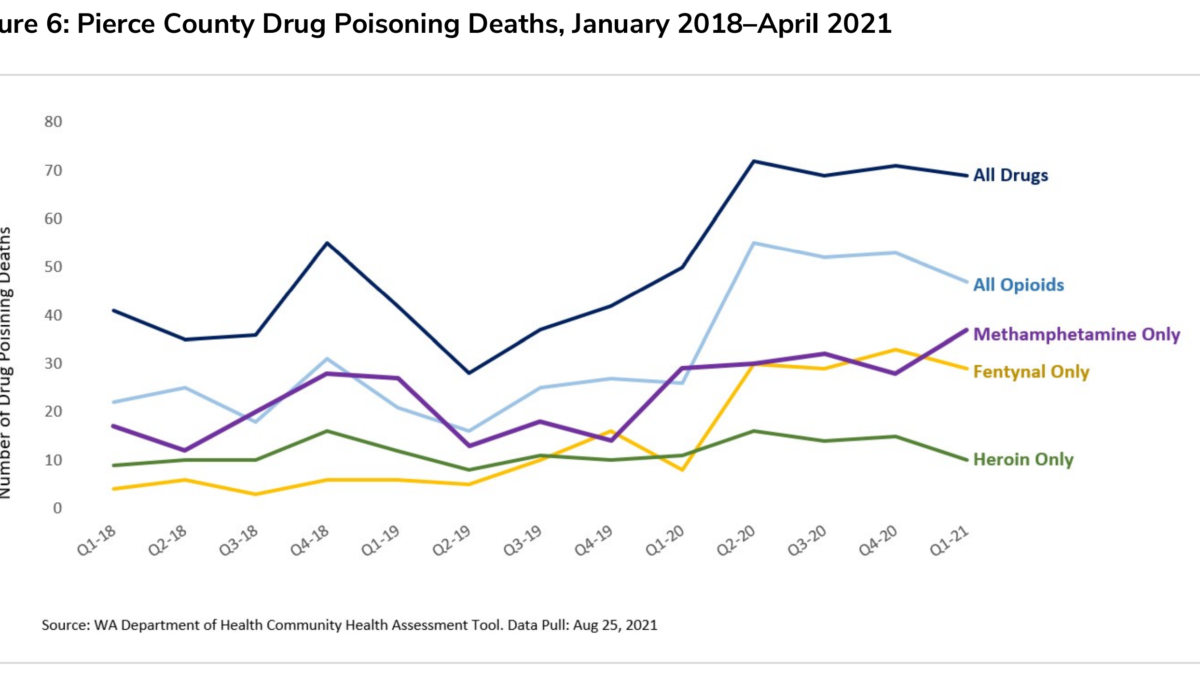

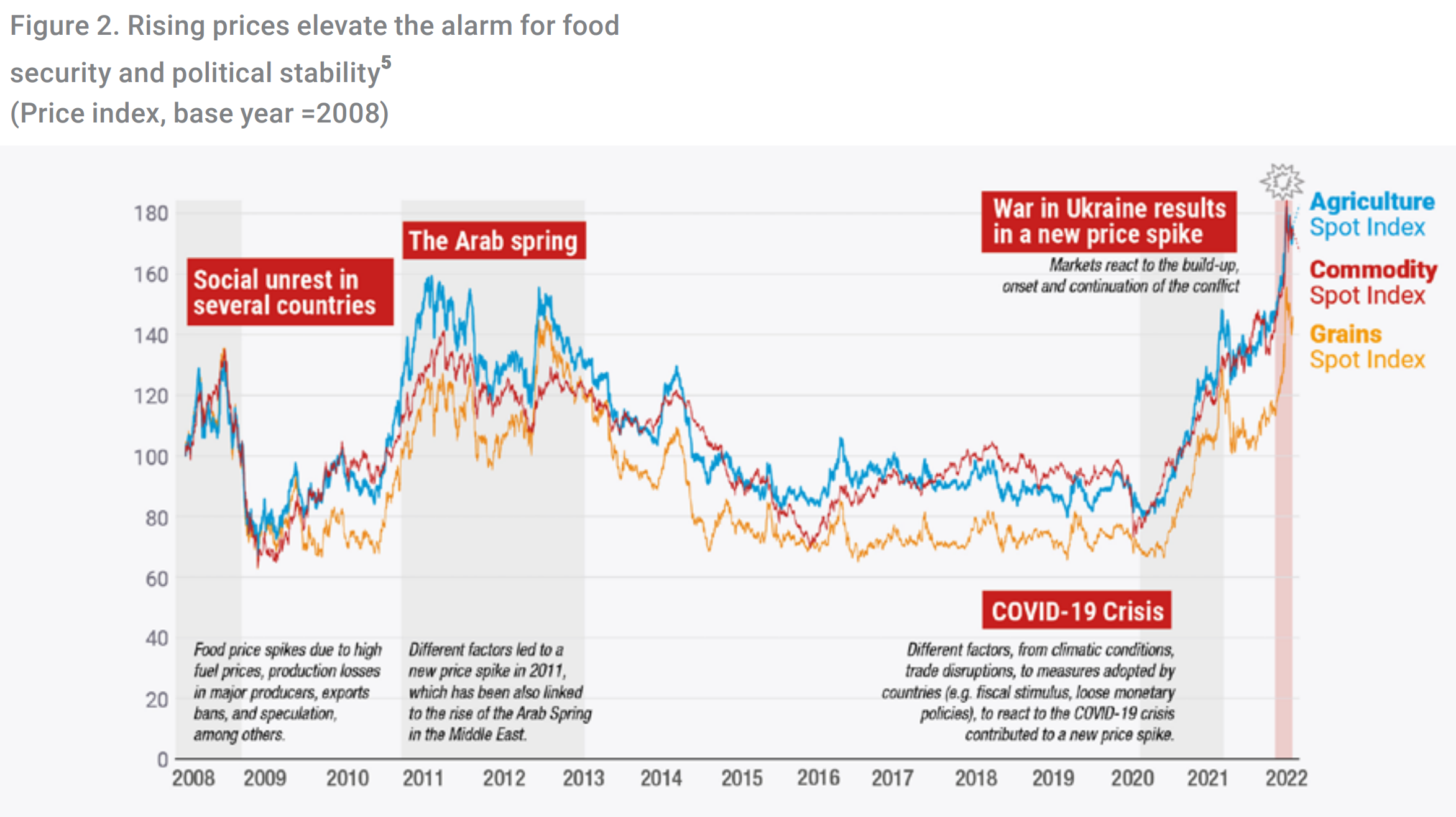

Across the world, low- and middle-income countries are struggling with a three-pronged crisis: the pandemic, the rising cost of their debt, and the increase in food and fuel prices caused by Russia’s invasion of neighbouring Ukraine.

David Malpass, the World Bank’s president, explained his concerns at the organisation’s spring meeting last month. “I’m deeply concerned about developing countries,” Malpass said. “They are facing sudden price increases for energy, fertiliser and food, and the likelihood of interest rate increases. Each one hits them hard.”

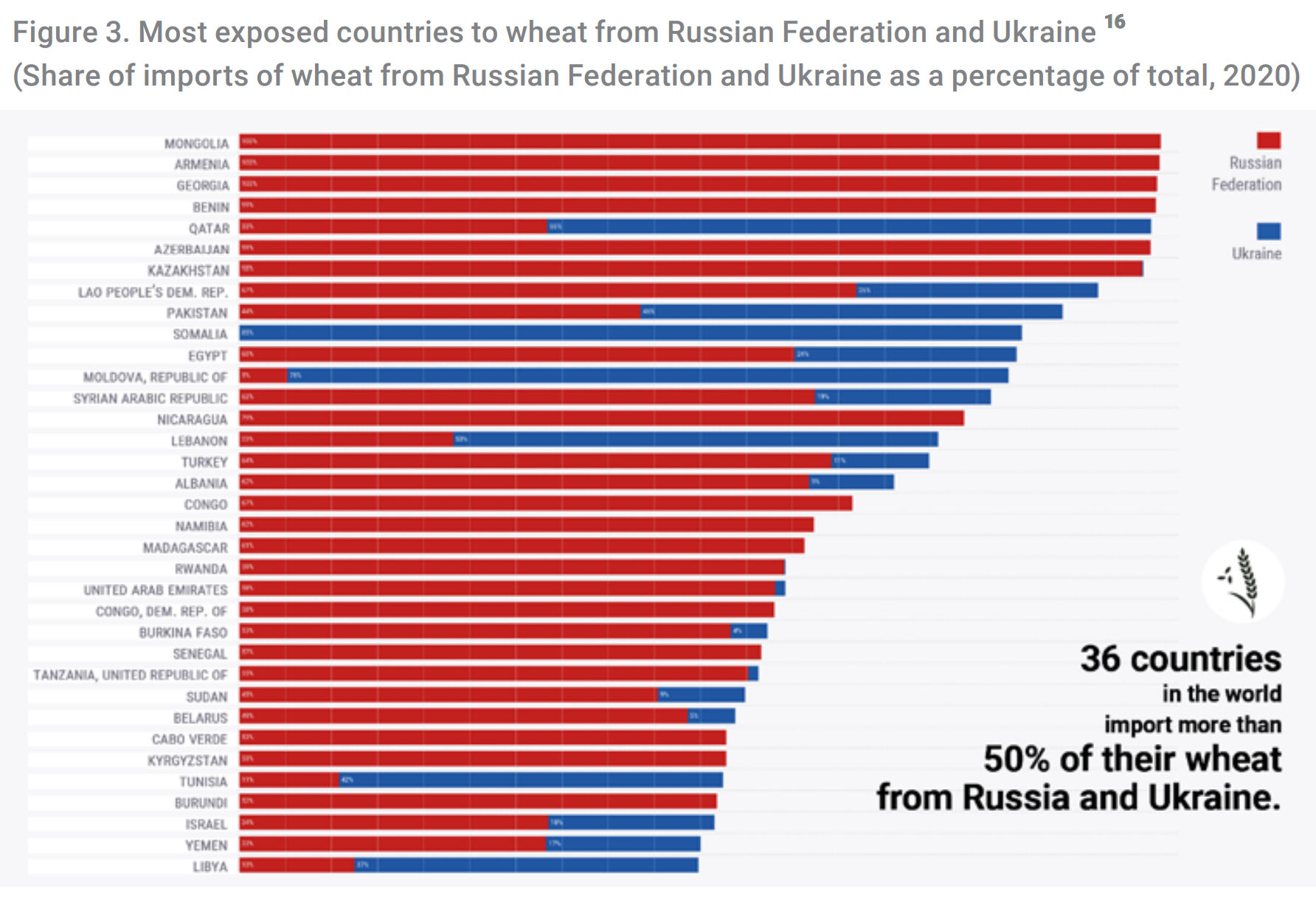

The UN has sought to quantify the problem. Its trade and development arm, UNCTAD, said in a recent report that there were 107 countries facing at least one of three shocks: rising food prices, rising energy prices or tighter financial conditions. All three shocks were being faced by 69 countries – 25 in Africa, 25 in Asia and the Pacific, and 19 in Latin America and the Pacific.

The list of countries that look vulnerable is long and varied. The IMF has opened rescue talks with Egypt and Tunisia – both big wheat importers from Russia and Ukraine – and with Pakistan, which has imposed power cuts because of the high cost of imported energy. Sub-Saharan African countries being carefully watched include Ghana, Kenya, South Africa and Ethiopia. Argentina recently signed a $45bn debt deal with the IMF, but other Latin American countries at risk include El Salvador and Peru.

For months there has been speculation that Turkey would be the first domino to fall, but despite an annual inflation rate of 70% and an unconventional approach to economic management, it is still standing. Unlike some other countries under threat, Turkey is able to feed its own people.

Richard Kozul-Wright, director of the globalisation and development strategies division at UNCTAD, said: “Countries have domestic problems but most of the shocks have nothing to do with those. The pandemic and the war had nothing to do with these countries, but have led to a huge increase in borrowing.”

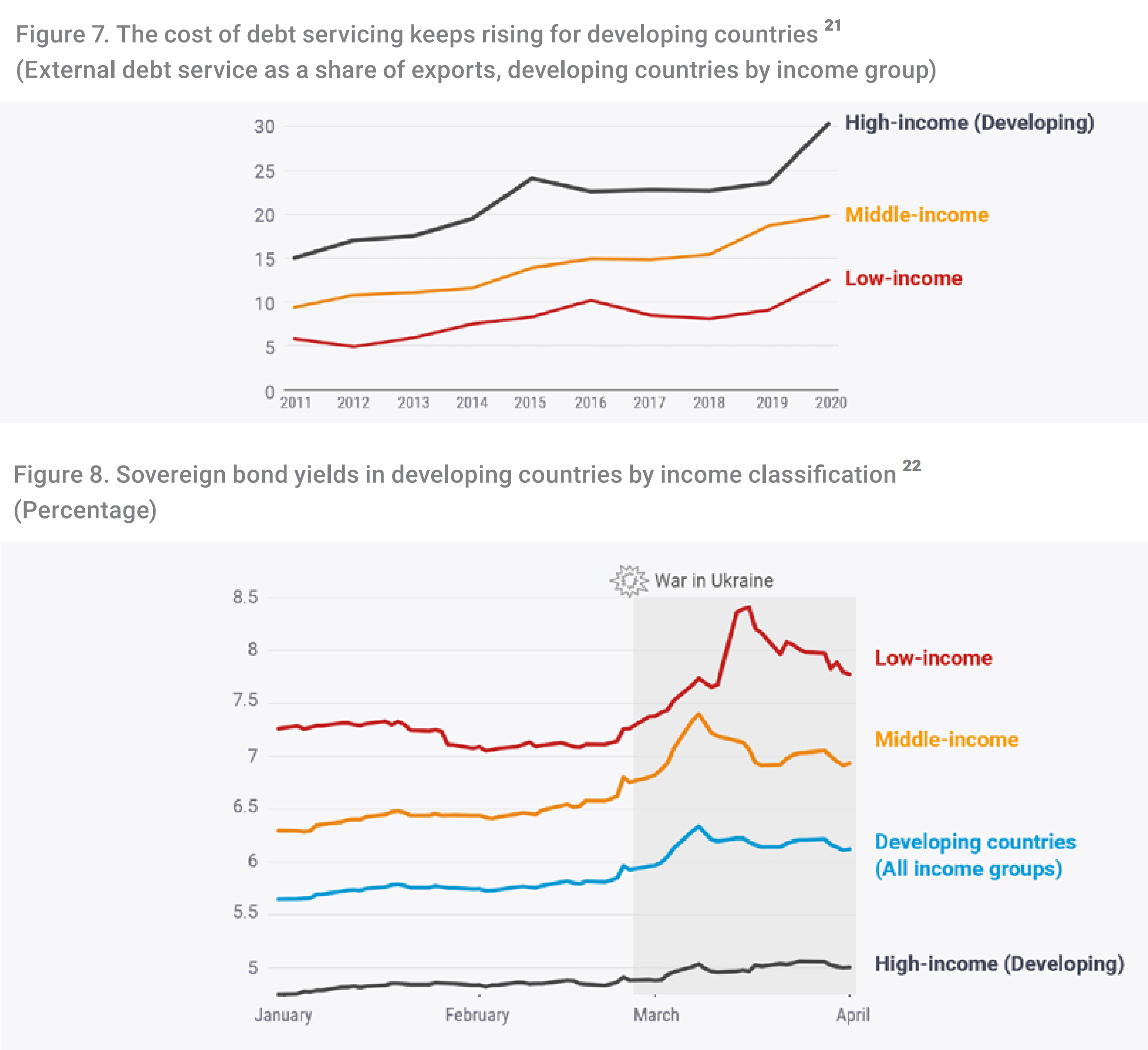

The World Bank said almost 60% of the lowest-income countries were in debt distress or at high risk of it before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while the cost of servicing borrowing is rising steeply, particularly for those countries that have amassed debts in foreign currencies. The war in Ukraine has led to investors seeking out the haven of the US dollar, pushing down the value of emerging market currencies. Higher interest rates from the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, have compounded the problem. [more]

Sri Lanka is the first domino to fall in the face of a global debt crisis

Is Bangladesh heading toward a Sri Lanka-like crisis?

By Arafatul Islam

18 May 2022

(DW) – Sri Lanka has been mired in economic turmoil over the past few months, with the country battling severe shortages of essential items and running out of petrol, medicines and foreign reserves amid an acute balance of payments crisis.

The resulting public fury targeting the government triggered mass street protests and political upheaval, forcing the resignation of Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa and his Cabinet, and the appointment of a new prime minister.

Many in Bangladesh fear that their country could face a similar situation, given the rising trade deficit and foreign debt burden.

Bangladesh imported goods worth $61.52 billion (€58.48 billion) in the first nine months of the 2021-2022 fiscal year, a rise of 43.9% compared to the same period last year.

Exports, however, rose at a slower pace of 32.9% while remittances from Bangladeshis living abroad — a key source of foreign exchange — dropped about 20% in the first four months of 2022 from the year before, to $7 billion.

“Foreign reserves will go down to a dangerous level”

Muinul Islam, a Bangladeshi economist and former professor at Chittagong University, fears that the trade deficit could grow in the coming years as imports are increasing at a faster pace than exports.

“Our imports are set to reach $85 billion by this year, while exports won’t be more than $50 billion. And, the trade deficit of $35 billion can’t be bridged by remittances alone,” Islam told DW, adding: “We will have to live with around a $10 billion shortfall this year.”

The expert also pointed out that Bangladesh’s foreign exchange reserves have fallen from $48 billion to $42 billion over the past eight months. He is worried that they may drop further in the coming months, likely down another $4 billion.

“If the trend of more imports against exports continues and we fail to minimize the gap with the remittances, our foreign reserves will go down to a dangerous level in the next three to four years,” he stressed, underlining that this would lead to a significant devaluation of the nation’s currency against the US dollar.

Massive loans for “white elephant” projects?

Bangladesh, like Sri Lanka, has also taken on foreign loans in recent years to fund what critics call “white elephant” projects, which are expensive but totally unprofitable.

These “unnecessary projects” could cause trouble when the time comes to repay the debts, Islam said.

“We have taken a loan of $12 billion from Russia for a nuclear power plant which has a production capacity of just 2,400 megawatts. We can repay the debt in 20 years but the installments will be $565 million per year from 2025,” he pointed out. “It’s the worst kind of a white elephant project.”

In total, the country will likely have to repay $4 billion per year from 2024, as installments for foreign loans, Islam estimated.

“I fear Bangladesh won’t be able to repay those loans at that time because of the shortage of income from the mega projects,” he stressed. [more]

Is Bangladesh heading toward a Sri Lanka-like crisis?

World on brink of “perfect storm” of crises, warns un chief calling for immediate action to avert cascading impacts of war in Ukraine – Dire consequences of the war on global food, energy, and financial markets could upend millions of lives

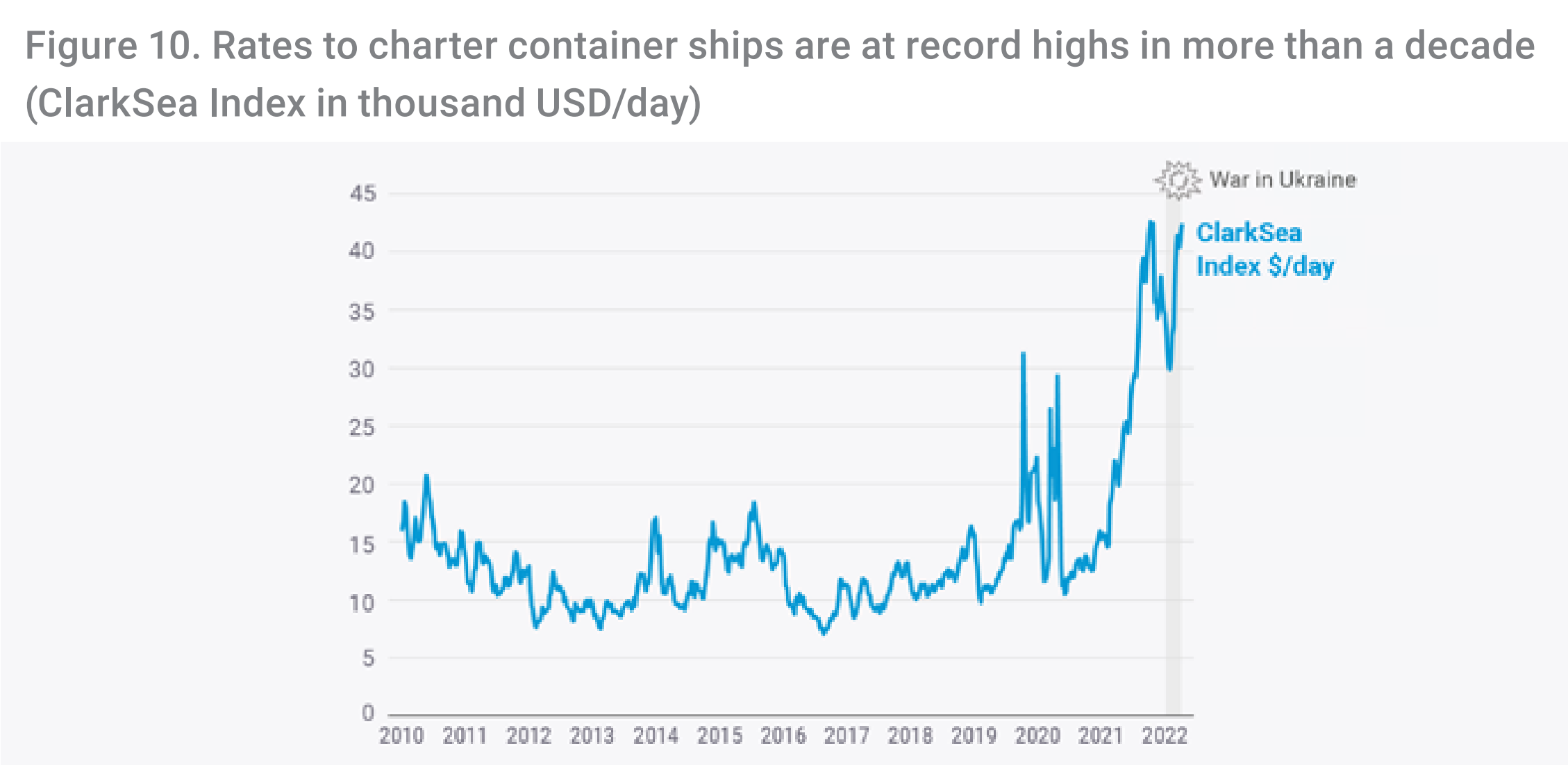

NEW YORK, United States of America, 13 April 2022 (UNCTAD) – The war in Ukraine is setting in motion a three-dimensional crisis – on food, energy and finance – that is producing alarming cascading effects to a world economy already battered by COVID-19 and climate change, according to the new findings of the Global Crisis Response Group (GCRG).

“We are now facing a perfect storm that threatens to devastate the economies of developing countries,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres. “The people of Ukraine cannot bear the violence being inflicted on them. And the most vulnerable people around the globe cannot become collateral damage in yet another disaster for which they bear no responsibility.”

“Our world cannot afford this. We need to act now,” stressed the Secretary-General calling for urgent, concrete and coordinated action to help countries and communities most at risk avert the interlinked crises. “We can do something about this three-dimensional crisis. We have the capacity to cushion the blow.”

On the brink of a perfect storm

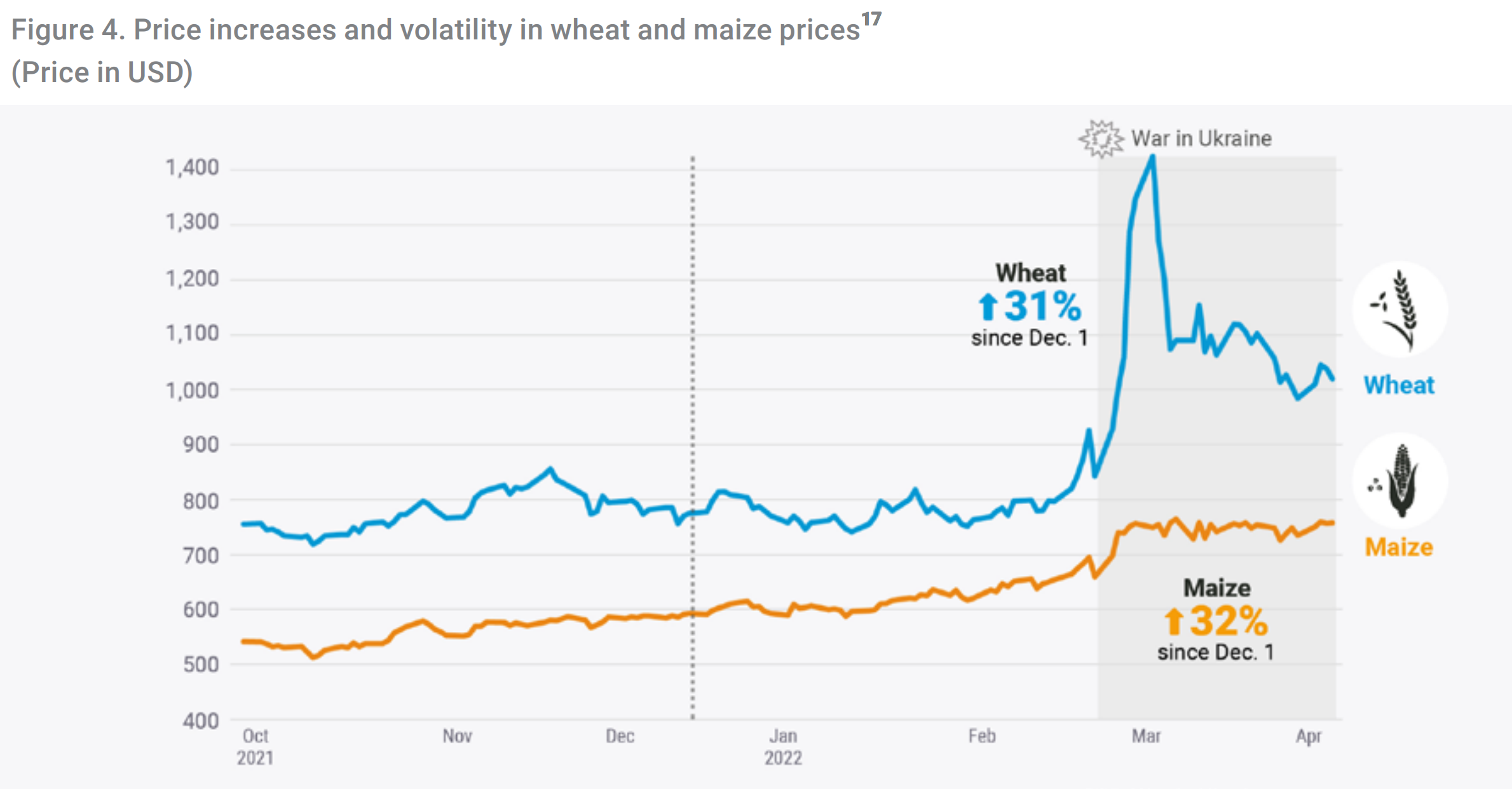

As two of the world’s breadbaskets, Russia and Ukraine provide around 30% of the wheat and barley we consume. Russia remains the world’s top natural gas exporter, second-largest oil exporter and a significant producer of fertilizers. The war has severely affected food, energy and financial markets, sending commodity prices to soar record high. Global economic growth is forecast to decrease by 1% in 2022.

Preliminary analysis suggests that as many as 1.7 billion people in 107 economies are exposed to at least one of three risks, mostly in Africa, Asia and the Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean. When combined with the already devastating impacts of the COVID-19 crisis and climate change, the exposure to just one risk is dire enough to cause debt distress, food shortages and blackouts.

Established by the Secretary-General, the GCRG aims to develop coordinated solutions to the interlinked crises in collaboration with governments, the multilateral system and sectors. The Steering Committee of the GCRG is chaired by UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed.

The goal is to help vulnerable countries avert large-scale crises through high-level coordination and partnerships, urgent action, and access to critical data, analysis and policy recommendations. The development of today’s brief, the first in a series, was coordinated by the Secretary-General of the UN Conference on Trade and Development, Rebeca Grynspan.

The world needs to act with urgency

The brief proposes a series of immediate to longer-term recommendations to avert and respond to the triple crisis, including the need to keep markets and trade open to ensure the availability of food, agricultural inputs such as fertilizer and energy. It also calls for international financial institutions to urgently release funding for the most at-risk countries while making sure there are enough resources to build long-term resilience to such shocks.

On food, beyond keeping markets open and ensuring that food is not subjected to export restrictions, the brief urges the prompt provision of funds for humanitarian food assistance. Food producers, who face higher input and transport costs, urgently need support for the next growing season.

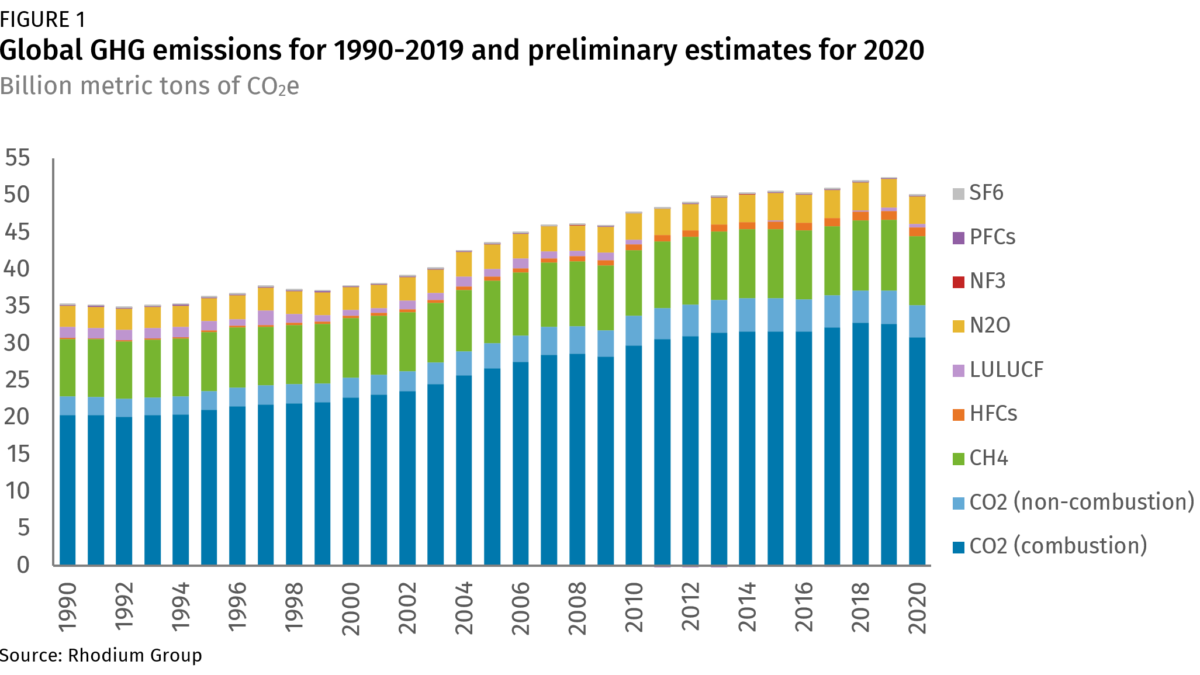

On energy, it calls on governments to use strategic stockpiles and additional reserves to help to ease this energy crisis in the short term. More importantly, the world needs to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy, which is not impacted by market fluctuations, to phase-out coal and all other fossil fuels.

“Now is also the time to turn this crisis into an opportunity. We must work towards progressively phasing-out coal and other fossil fuels, and accelerating the deployment of renewable energy and a just transition,” added the Secretary-General.

On finance, the brief asks the international financial system, including G20 countries and development banks, to provide flexible, urgent, and sufficient funding for particularly least developed countries, and relief from debt servicing under current conditions.

“We need to pull developing countries back from the financial brink. The international financial system has deep pockets,” said the Secretary-General asking for funds to be made available to “economies that need them most so that governments can avoid default, provide social safety nets for the poorest and most vulnerable, and continue to make critical investments in sustainable development.”

“Above all, this war must end. We need to silence the guns and accelerate negotiations towards peace, now. For the people of Ukraine. For the people of the region. And for the people of the world,” he added.

The launch of the findings comes ahead of the 2022 Spring Meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group (18 to 24 April 2022).

Contact

- UN Department of Global Communications | Devi Palanivelu | palanivelu@un.org

- UN Conference on Trade and Development | Dan Teng’o | dan.tengo@unctad.org