After the Australia floods, the distressing but necessary case for managed retreat – “Is it fair for taxpayers to carry the huge burden of paying for future rescue and relief costs?”

By Antonia Settle

13 March 2022

(The Conversation) – From Brisbane to Sydney, many thousands of Australians have been reliving a devastating experience they hoped – in 2021, 2020, 2017, 2015, 2013, 2012 or 2010/11 – would never happen to them again.

For some suburbs built on the flood plains of the Nepean River in western Sydney, for example, these floods are their third in two years.

Flooding is a part of life in parts of Australia. But as climate change intensifies the frequency and severity of floods, fires and other disasters, and recovery costs soar, two big questions arise.

As a society, should we be setting up individuals and families for ruin by allowing them to build back in areas where they can’t afford insurance? And is it fair for taxpayers to carry the huge burden of paying for future rescue and relief costs?

Considering ‘managed retreat’

Doing something about escalating disaster risks require multiple responses. One is making insurance as cheap as possible. Another is investing in mitigation infrastructure, such as flood levees. Yet another is about making buildings more disaster-resistant.

The most controversial response is the policy of “managed retreat” – abandoning buildings in high-risk areas.

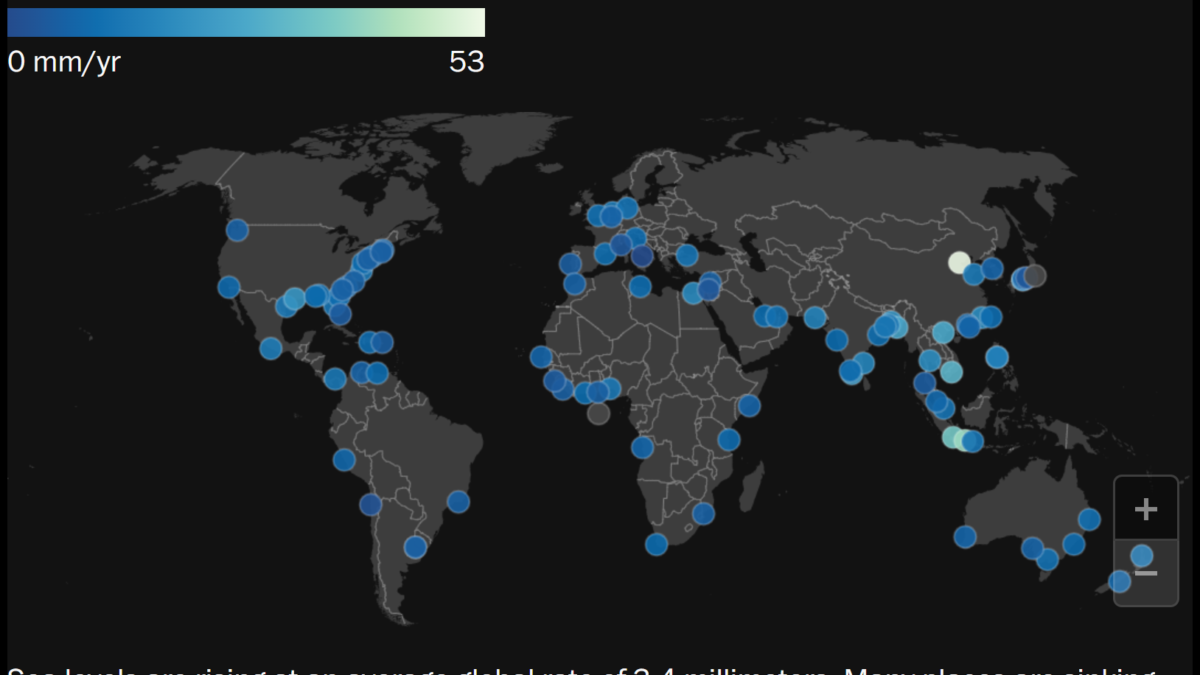

In Australia this policy has been mostly discussed as something to consider some time in the future, and mostly for coastal communities, for homes that can’t be saved from rising sea levels and storm surges.

It’s a sensitive subject because it uproots families, potentially hollows outs communities and also affects house prices – an unsettling prospect when economic security is tied to home ownership.

But managed retreat may also be better than the chaotic consequences of letting the market alone try to work out the risks to individuals and communities.

Grand Forks: a case study

The strategy is already being implemented in parts of western Europe and North America. An example from Canada is the town of Grand Forks, a community of about 4,000 people 300 kilometres east of Vancouver.

The town is located where two rivers meet. In May 2018 it experienced its worst flooding in seven decades, after days of extreme rain attributed to higher than normal winter snowfall melting quickly in hotter spring temperatures. Deforestation has been blamed for exacerbating the flood.

The flood damaged about 500 buildings in Grand Forks, with lowest-income neighbourhoods in low-lying areas the worst-affected.

In the aftermath the local council received C$53 million from the federal and provincial governments for flood mitigation. This included work to reinforce river banks and build dikes. About a quarter of the money was allocated to acquire about 80 homes in the most flood-prone areas.

The decision to demolish these homes – about 5% of the town’s housing – and return the area to flood plain has been contentious.

Some residents simply didn’t want to sell. Adding to the pain was owners being paid the post-flood market value of their homes (saving the council about C$6 million). There were also long delays, with residents stuck in limbo for more than year while authorities finalised transactions. [more]

After the floods, the distressing but necessary case for managed retreat