Nearly half of U.S. honeybee colonies died in the 2022-2023 season – “This is a very troubling loss number when we barely manage sufficient colonies to meet pollination demands in the U.S.”

By Seth Borenstein

22 June 2023

WASHINGTON (AP) – America’s honeybee hives just staggered through the second highest death rate on record, with beekeepers losing nearly half of their managed colonies, an annual bee survey found.

But using costly and Herculean measures to create new colonies, beekeepers are somehow keeping afloat. Thursday’s University of Maryland and Auburn University survey found that even though 48% of colonies were lost in the year that ended April 1, the number of United States honeybee colonies “remained relatively stable.”

Honeybees are crucial to the food supply, pollinating more than 100 of the crops we eat, including nuts, vegetables, berries, citrus and melons. Scientists said a combination of parasites, pesticides, starvation, and climate change keep causing large die-offs.

Last year’s 48% annual loss is up from the previous year’s loss of 39% and the 12-year average of 39.6%, but it’s not as high as 2020-2021’s 50.8% mortality rate, according to the survey funded and administered by the nonprofit research group Bee Informed Partnership. Beekeepers told the surveying scientists that 21% loss over the winter is acceptable and more than three-fifths of beekeepers surveyed said their losses were higher than that.

“This is a very troubling loss number when we barely manage sufficient colonies to meet pollination demands in the U.S.,” said former government bee scientist Jeff Pettis, president of the global beekeeper association Apimondia that wasn’t part of the study. “It also highlights the hard work that beekeepers must do to rebuild their colony numbers each year.”

The overall bee colony population is relatively steady because commercial beekeepers split and restock their hives, finding or buying new queens, or even starter packs for colonies, said University of Maryland bee researcher Nathalie Steinhauer, the survey’s lead author. It’s an expensive and time-consuming process.

The prognosis is not as bad as 15 years ago because beekeepers have learned how to rebound from big losses, she said.

“The situation is not really getting worse, but it’s also not really getting better,” Steinhauer said. “It is not a bee apocalypse.”

Despite big annual losses the situation is a far cry from 2007 when many bee experts expected an end to managed pollination said U.S. Department Agriculture research entomologist Jay Evans, who wasn’t part of the survey.

“There are threats certainly in the environment and honeybees have persisted,” Evans said. “I don’t think honeybees will go extinct but I think they will always have these sort of challenges.”

Some commercial beekeepers who have succeeded in the past lost as much as 80% of their colonies this past year, while other beekeepers did well, it varied so much, Evans said. Pettis, who has 150 colonies on Maryland’s Eastern shore, had less than 18% loss, saying he used organic acids for mite control. […]

Another problem is landscapes that have only one crop or homogenous landscapes which deprive bees of food, while pesticides and bouts of extreme weather also have caused problems.

For example, in the Washington, D.C. area unusual 80-degree warmth in January brought some bees out of their normal winter routine and then when it turned cool again, they had problems, Evans said.

“The impact of climate change on bee colony survival is real and can go undetected,” Pettis said in an email. [more]

Nearly half of US honeybee colonies died last year. Struggling beekeepers stabilize population

![Self-reported causes of colony loss over summer 2022 (1 April – 1 October, in yellow) and winter 2022-23 (1 October – 1 April, in blue), as reported by US beekeepers grouped by operation type: backyard (managing up to 50 colonies), sideline (managing 51-500), and commercial (managing >500 colonies). Number of respondents: backyard (summer: 1,495, winter: 2,070), sideline (summer: 64, winter: 97) and commercial (summer: 35, winter: 41) beekeepers. The arrow represents the proportion of beekeepers having selected the specific cause of loss in a list of multiple choices associated with the question: “What factors do you think were the most prominent cause(s) of colony death in your operation in [season]?”. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval obtained from a bootstrap resampling of the data (n-out-of-n, 1000 rep). Legend: Pesticides (Non-apicultural pesticides); Pollen (Nutritional stress (pollen deprivation)); Predators (e.g., bears); Queen issues; Starvation (honey/nectar/sugar water); Varroa (varroa mites and associated viruses); Weather (adverse weather (e.g., drought, cold snap)); DK (Don’t know). Answers selected by less than 10% of respondents in all three groups are not shown. Other multiple choices options not listed in the figure: Brood diseases (e.g., AFB, EFB), Natural disaster (e.g., hurricane, flood), Apicultural treatments (e.g., formic acid, amitraz), Shipping stress (e.g., overheating, truck issues), Equipment failure (e.g., moisture, ventilation), Failure of environmental controls in sheds, Scavenger pests (e.g., small hive beetle, wax moth). Graphic: Bee Informed Partnership](https://desdemonadespair.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/image-89.png)

United States honeybee colony losses 2022–2023: Preliminary results from the bee informed partnership

By Nathalie Steinhauer

22 June 2023

(Bee Informed Partnership) – […] The survey is a retrospective online questionnaire, which relies on voluntary participation of beekeepers across the country during the month of April. The 2023 survey covered the one-year period between April 2022 and April 2023. Small scale beekeepers (1-50 colonies) and large-scale beekeepers (>50 colonies) took slightly different versions of the survey (survey question previews can be found at https://beeinformed.org/citizen-science/loss-and-management-survey/).

This year, 3,006 beekeepers from across the United States provided valid survey responses. These beekeepers collectively managed 314,360 colonies on 1 October 2022, representing 12% of the estimated 2.70 million managed honey-producing colonies in the country in 2022 (USDA NASS, 2023).

Colony loss rates were calculated as the ratio of the number of colonies lost to the number of colonies managed over a defined period. Loss rates should not be interpreted as a change in population size, but are best interpreted as a mortality rate. High levels of losses do not necessarily result in a decrease in the total number of colonies managed in the United States because beekeepers can replace lost colonies throughout the year.

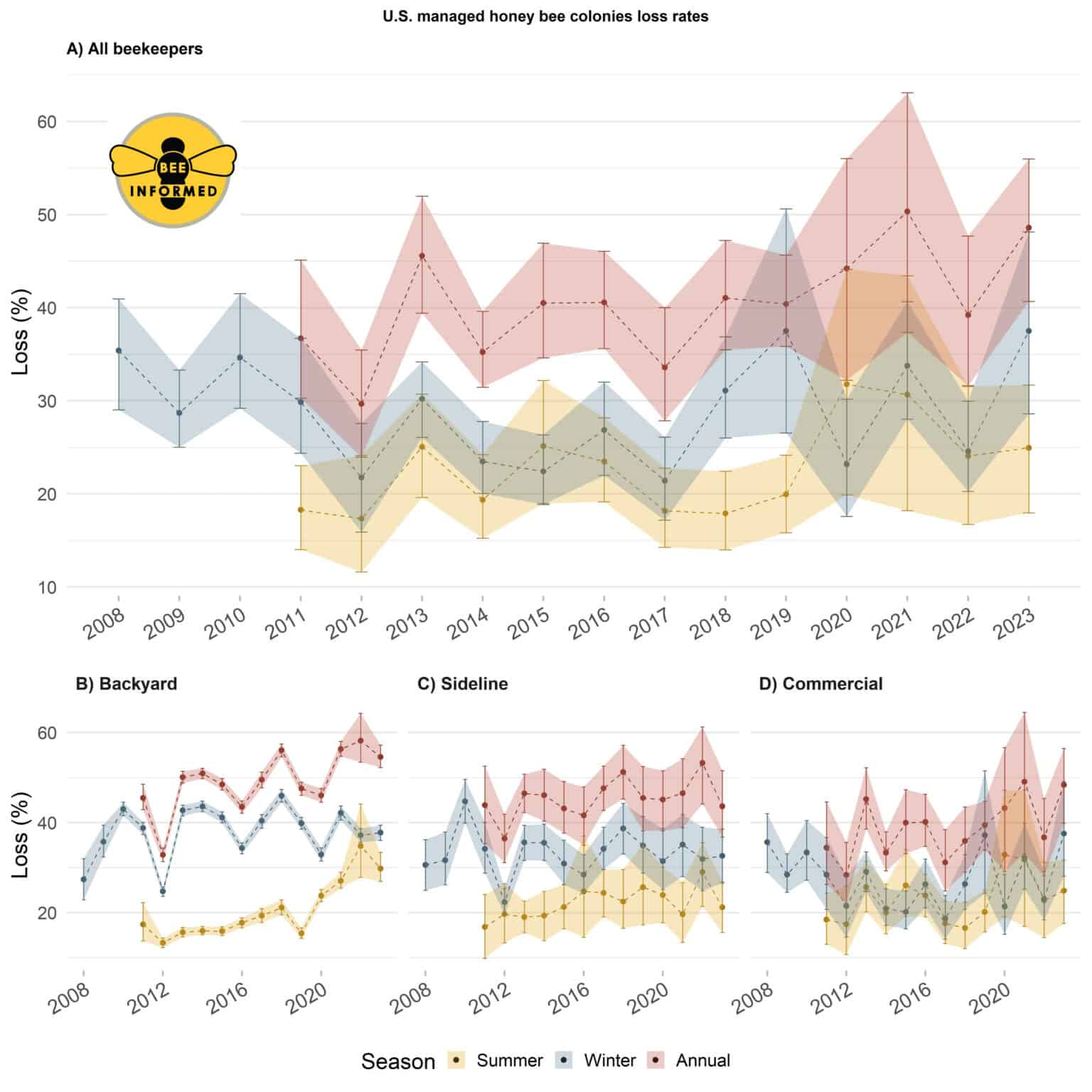

During summer 2022 (1 April 2022 – 1 October 2022), an estimated 24.9% [18.0 – 31.7, 95% bootstrapped confidence interval (CI)[1]] of managed colonies were lost in the United States (Fig. 1). This was on par with recent years. The summer loss rate was just 1.1 percentage point (pp) higher than last year’s estimated summer colony loss (23.8% [16.7 – 31.5 CI]), and 2.2 pp higher than the average summer loss reported by beekeepers since the summer of 2010 (22.6%, 12-year average), when summer losses were first monitored.

During winter 2022-2023 (1 October 2022 – 1 April 2023), an estimated 37.4% [28.6 – 48.1 CI] of managed colonies in the United States were lost (Fig. 1). This winter loss rate was 13.2 pp in excess of the previous winter loss rate (24.2% [20.3 – 29.9 CI]), and 9.1 pp higher than the average winter loss (28.2%, 15-year average) reported by beekeepers since the start of the survey in 2008, making 2022-2023 the second highest year of winter loss after 2018-2019 (37.7% [26.5 – 50.6 CI]). The percentage of colony loss over the winter deemed “acceptable” by beekeepers was on average 21.3% in 2022-2023, which was on par with the previous nine years during which the acceptable loss has hovered around 20%. In 2022-2023, over 60% of the surveyed beekeepers reported winter loss above this threshold.

Over the entire year (1 April 2022 – 1 April 2023), beekeepers in the United States lost an estimated 48.2% [40.7 – 56.0 CI] of their managed honeybee colonies (Fig. 1). This was 9.2 pp higher than last year’s estimated annual loss (39.0% [31.6 – 47.7 CI]), nearly as high as (2.6 pp lower than) the highest annual loss on record (2020-2021, 50.8% [37.4 – 63.1 CI]), and 8.5 pp higher than the average loss rate (39.6%, 12-year average) over the last 12 years.

The honeybee industry in the United States can be loosely divided into three groups of beekeepers − backyard (managing up to 50 colonies), sideline (managing 51-500), and commercial (managing >500 colonies), with the majority of colonies being managed by commercial operations, even though they are a small proportion of beekeepers (1.4% of the surveyed beekeepers, who collectively managed 89.7% of surveyed colonies in 2022-2023).

As in previous years, backyard beekeepers experienced a higher annual rate of loss than commercial beekeepers in 2022-2023 (54.6% [52.2 – 57.2 CI] for backyard vs 47.9% [39.9 – 56.4 CI] for commercial). This represented a higher loss year than average for both backyard beekeepers (5.8 pp more than their 12-year average of 48.8%) and commercial beekeepers (9.7 pp more than their 12-year average of 38.2%), but it seems issues occurred at different times of the year for the two groups.

Backyard beekeepers again experienced one of their highest summer losses on record (the last 4 years classified as the top 4, 3, 1 and 2, respectively, in the 13-year record), with 29.8% summer 2022 loss [26.9 – 33.4 CI], this was 10.0 pp over the previous 12-year average of 19.8%. Commercial beekeepers reported summer losses (24.7% [17.6 – 31.7 CI]) on par (1.8 pp over) with their average over the previous 12 years (22.8%).

Though the loss rates of both groups were comparable for the winter season (37.8% [36.0 – 39.4 CI] for backyard beekeepers, and 37.6% [28.1 – 49.1 CI] for commercial beekeepers), this represented a high loss season for the commercial group (10.7 pp over their 27.0% 15-year average), but an average season for backyard beekeepers (0.2 pp lower than their 38.0% 15-year average). Such high winter loss rates for commercial beekeepers have only been reported once before in this survey, in 2018-2019.

The most prominent cause of colony death reported by beekeepers over the winter 2022-23 was “varroa” (Varroa destructor, and its associated viruses), for all three operation types (Fig. 2). Backyard beekeepers then tended to cite “adverse weather” and “starvation” (meaning lack of honey, nectar, or sugar water) as the second and third most prominent causes of winter colony loss in their operations. Sideline beekeepers equally cited “queen issues” and “starvation” as their second most prominent cause of winter loss. Commercial beekeepers cited equally “queen issues” and “adverse weather”.

In the summer of 2022, the most prominent cause of colony death reported by beekeepers of all operation types was “queen issues” (Fig. 2). Both backyard and sideline beekeepers then listed “varroa” and “adverse weather”. Commercial beekeepers cited “varroa” as frequently as “queen issues” as their most prominent causes of loss over the summer, followed by “adverse weather”.

Although the total number of honeybee colonies in the country has remained relatively stable over the last 20 years (~2.6 million colonies according to the USDA NASS Honey Reports), loss rates remain high, indicating that beekeepers are under substantial pressure to recover from losses by creating new colonies every year. The Bee Informed Partnership’s annual Colony Loss and Management Survey offers an important record of such loss rates experienced by beekeepers across the United States each year. Until the survey was launched in 2007, there was no rigorous record of loss rates of managed honeybee colonies, making it difficult to compare losses against historic levels.

To obtain more information about Bee Informed Partnership’s annual national Colony Loss and Management Survey, visit: https://beeinformed.org/citizen-science/loss-and-management-survey/.

State-level estimates, including estimates for single-state and multi-state operations, will be published on https://research.beeinformed.org/loss-map/.

[1] Confidence intervals were obtained from the distribution of bootstrapped estimates for each group of respondents (n-out-of-n method, 1000 rep). Due to the stochastic nature of bootstrap analyses, 95% CI are expected to vary slightly at each computation.

Thank you to everyone who took the time to complete and share the survey! [more]

United states honey bee colony losses 2022–23: Preliminary results from the bee informed partnership