Tax breaks for the rich don’t boost the economy – “Our research shows that the economic case for keeping taxes on the rich low is weak”

16 December 2020 (LSE) – Major reforms reducing taxes on the rich lead to higher income inequality but do not have any significant effect on economic growth or unemployment, according to new research by LSE and King’s College London.

Researchers say governments seeking to restore public finances following the COVID-19 crisis should therefore not be concerned about the economic consequences of higher taxes on the rich.

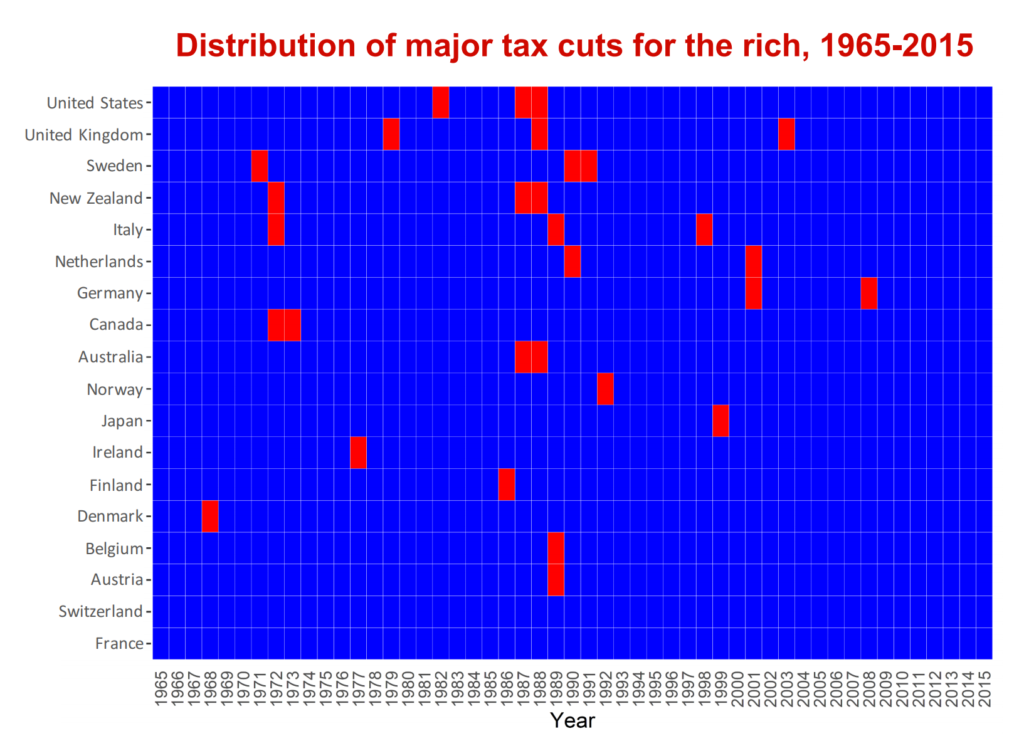

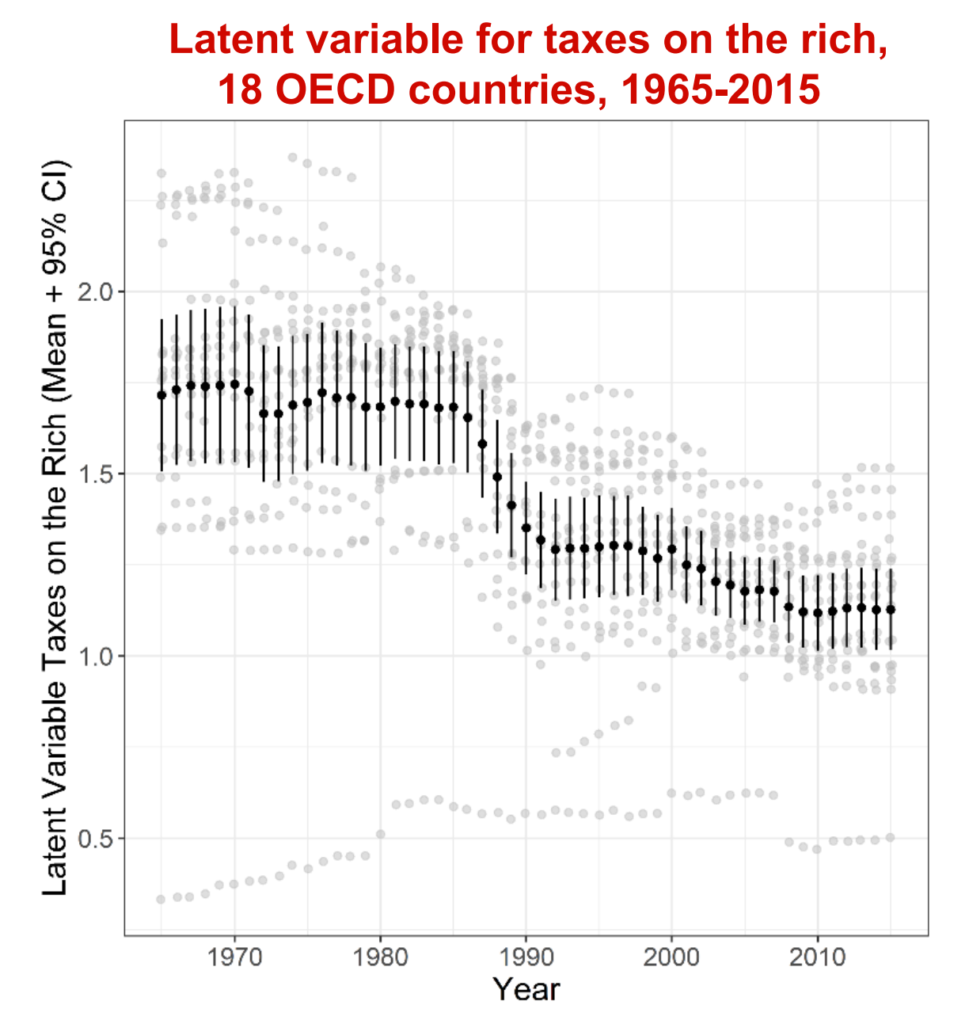

The paper, published by LSE’s International Inequalities Institute, uses data from 18 OECD countries, including the UK and the US, over the last five decades. The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich, by David Hope and Julian Limberg, shows that the last 50 years were a period of falling taxes on the rich in the advanced economies. Major tax cuts were spread across countries and throughout the observation period but were particularly clustered in the late 1980s.

Our results might be welcome news for governments as they seek to repair the public finances after the COVID-19 crisis, as they imply that they should not be unduly concerned about the economic consequences of higher taxes on the rich.

Dr. Julian Limberg, Lecturer in Public Policy at King’s College London

It states: “Our results show that…major tax cuts for the rich increase the top 1% share of pre-tax national income in the years following the reform. The magnitude of the effect is sizeable; on average, each major reform leads to a rise in top 1% share of pre-tax national income of 0.8 percentage points. The results also show that economic performance, as measured by real GDP per capita and the unemployment rate, is not significantly affected by major tax cuts for the rich. The estimated effects for these variables are statistically indistinguishable from zero.”

It continues: “Our findings on the effects of growth and unemployment provide evidence against supply side theories that suggest lower taxes on the rich will induce labour supply responses from high-income individuals (more hours of work, more effort etc.) that boost economic activity. They are, in fact, more in line with recent empirical research showing that income tax holidays and windfall gains do not lead individuals to significantly alter the amount they work.”

The authors conclude: “Our results have important implications for current debates around the economic consequences of taxing the rich, as they provide causal evidence that supports the growing pool of evidence from correlational studies that cutting taxes on the rich increases top income shares, but has little effect on economic performance.”

Dr Hope, Visiting Fellow at LSE’s International Inequalities Institute and Lecturer in Political Economy at King’s College London, said: “Our research shows that the economic case for keeping taxes on the rich low is weak. Major tax cuts for the rich since the 1980s have increased income inequality, with all the problems that brings, without any offsetting gains in economic performance.”

Dr Limberg, Lecturer in Public Policy at King’s College London, said: “Our results might be welcome news for governments as they seek to repair the public finances after the COVID-19 crisis, as they imply that they should not be unduly concerned about the economic consequences of higher taxes on the rich.”

The countries studied in the paper are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.