EIU Democracy Index 2022: Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine – “Overall the story is one of stagnation. This is a dismal result given that in 2022 the world started to move on from the pandemic-related suppression of individual liberties that persisted through 2020 and 2021”

1 February 2023 (EIU) – The Democracy Index, which began in 2006, provides a snapshot of the state of democracy worldwide in 165 independent states and two territories. This covers almost the entire population of the world and the vast majority of the world’s states (microstates are excluded). The Democracy Index is based on five categories: electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties. Based on its scores on a range of indicators within these categories, each country is then classified as one of four types of regime: “full democracy”, “flawed democracy”, “hybrid regime” or “authoritarian regime”. A full methodology and explanations can be found in the Appendix.

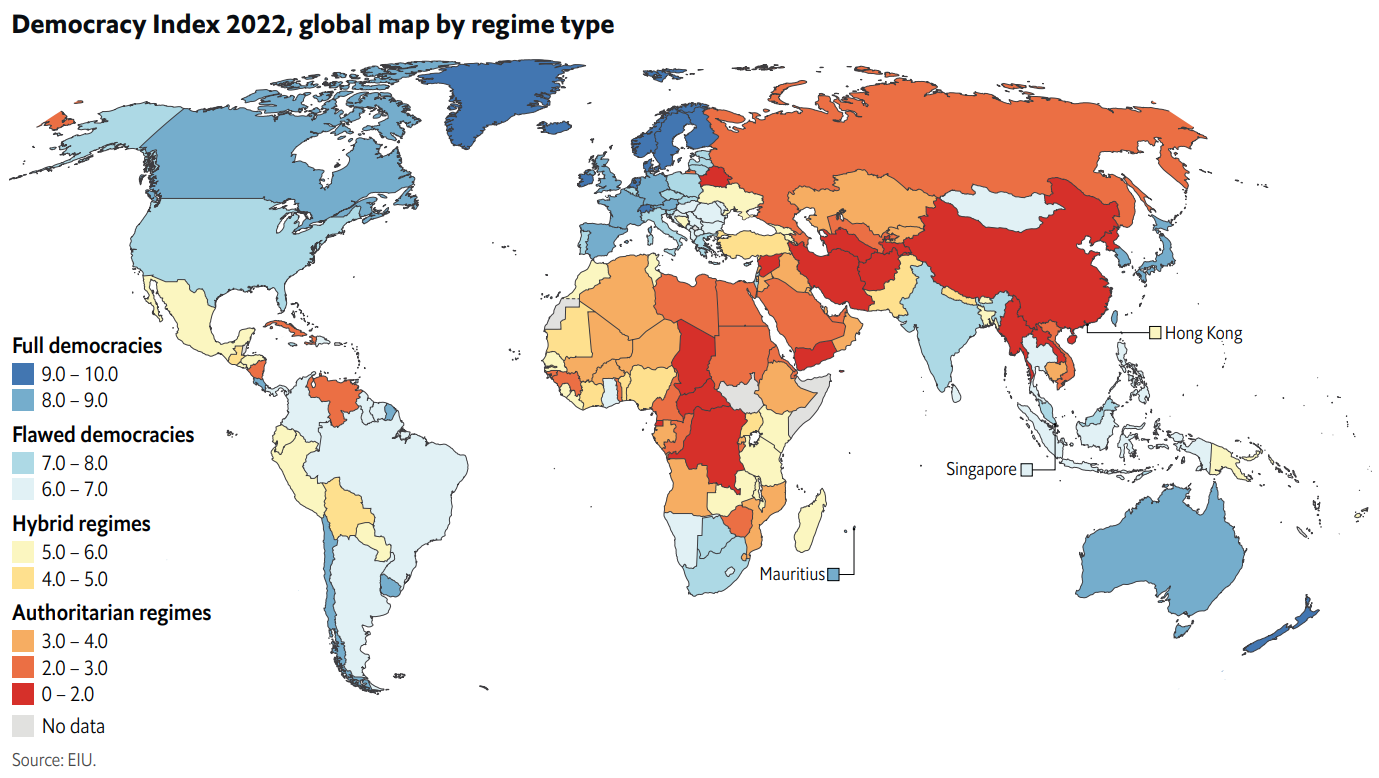

This edition of the Democracy Index examines the state of global democracy in 2022. The global results are discussed in this introduction, and the results by region are analysed in greater detail in the section entitled “Democracy around the regions in 2022” (see page 30). According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s measure of democracy, almost half of the world’s population live in a democracy of some sort (45.3%). Only 8% reside in a “full democracy”, compared with 8.9% in 2015, before the US was demoted from a “full democracy” to a “flawed democracy” in 2016. More than one-third of the world’s population live under authoritarian rule (36.9%), with a large share of them being in China and Russia.

According to the 2022 Democracy Index, 72 of the 167 countries and territories covered by the model, or 43.1% of the total, can be considered to be democracies. The number of “full democracies” increased to 24 in 2022, up from 21 in 2021, as Chile, France, and Spain re-joined the top-ranked countries (those scoring more than 8.00 out of 10). The number of “flawed democracies” fell by five to 48 in 2022. Of the remaining 95 countries in our index, 59 are “authoritarian regimes”, the same as in 2021, and 36 are classified as “hybrid regimes”, up from 34 the previous year. (For a full explanation of the index methodology and categories, see pp 66-68.)

From regression to stagnation: no post-lockdown revival

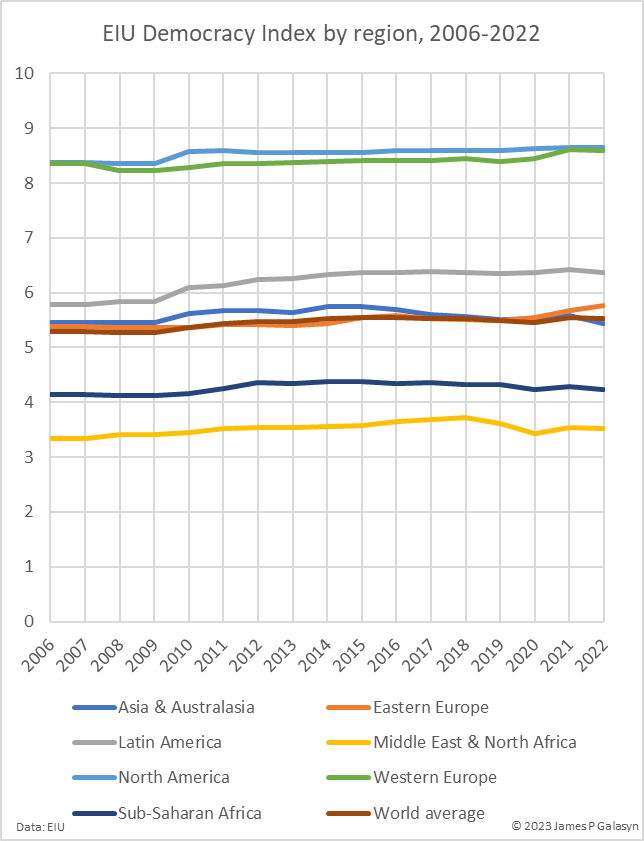

Overall, the story is one of stagnation, with the global average score remaining essentially unchanged at 5.29 (on a 0-10 scale), compared with 5.28 in 2021. This is a dismal result given that in 2022 the world started to move on from the pandemic-related suppression of individual liberties that persisted through 2020 and 2021. More countries managed to improve their score in 2022 than in 2021 (75 compared with 47), but more than half of the countries measured by the index (92) either stagnated or declined in terms of their average index score. With the exception of western Europe, which improved its average index score decisively, the scores for every other region of the world did not budge much, either upwards or downwards.

This picture of stagnation in the state of global democracy hides darker developments. Strikingly, the situation in two countries that are home to more than 20% of the world’s population, China and Russia, took a decisive turn for the worse in 2022. Russia recorded the biggest decline in score of any country in the world in 2022. Its invasion of Ukraine was accompanied by all-out repression and censorship at home. Russia has been on a trajectory away from democracy for a long time and is now acquiring many of the features of a dictatorship. Meanwhile, until the end of 2022, China doubled down on its zero-covid policy, using the most draconian methods to stop the spread of the virus, locking up tens of millions of people for prolonged periods until protests erupted towards the end of the year. Fearing the spread of mass protests more than the spread of the disease, the Chinese authorities abandoned their zero-covid policy in December 2022. However, the state’s repressive approach to all manifestations of dissent has not been jettisoned, resulting in a further decline in China’s already low score in the Democracy Index in 2022.

Sovereignty, democracy and the battle for Ukraine

By far the biggest event of the year was Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, a flagrant violation of Ukrainian sovereignty that sent shockwaves around the world. Russia’s actions have brought home to many the vital importance of defending national sovereignty, without which real freedom and democracy are unattainable. We examine the relationship between sovereignty and democracy in the context of Ukraine’s fight for self-determination in a special essay in the second section of the report (see page 19). This suggests that Ukraine’s defence of its national sovereignty is inseparable from the task of building a democratic nation state.

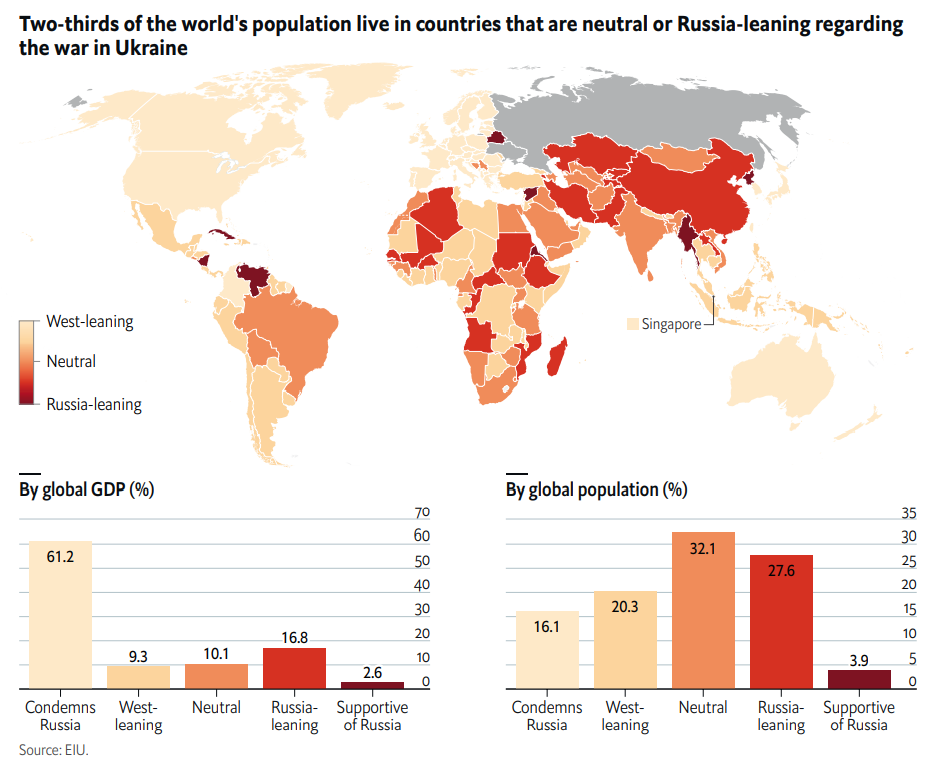

We also consider why many countries in the global south have not followed the US, UK, the EU and others in taking sides against Russia. Their reluctance to line up behind Western countries reflects, variously, frustration with the established international order; resentment of perceived Western hypocrisy in the context of past Western meddling and intervention in their affairs; and dependency on Russian minerals and other resources. The principle of national sovereignty is too important to be sacrificed on the altar of anti-Westernism, but the inconsistent application of the principle by Western powers has bred cynicism that is now making it more difficult for Western countries to attract support from the global south. Our special essay argues that national sovereignty is the bedrock of freedom, democracy and citizenship and is a principle that needs to be rehabilitated.

Democracy in the doldrums

From a global perspective the year 2022 was a disappointing one for democracy, given expectations that there might be a rebound in the overall index score as pandemic-related prohibitions were lifted over the course of the year. Instead, the average global score stagnated. At 5.29, it scarcely improved from the 5.28 recorded in 2021. This leaves the index score well below the pre-pandemic global average of 5.44, and even further below the historical high of 5.55 recorded in 2014 and 2015 (and also in 2008, just before the global financial crisis).

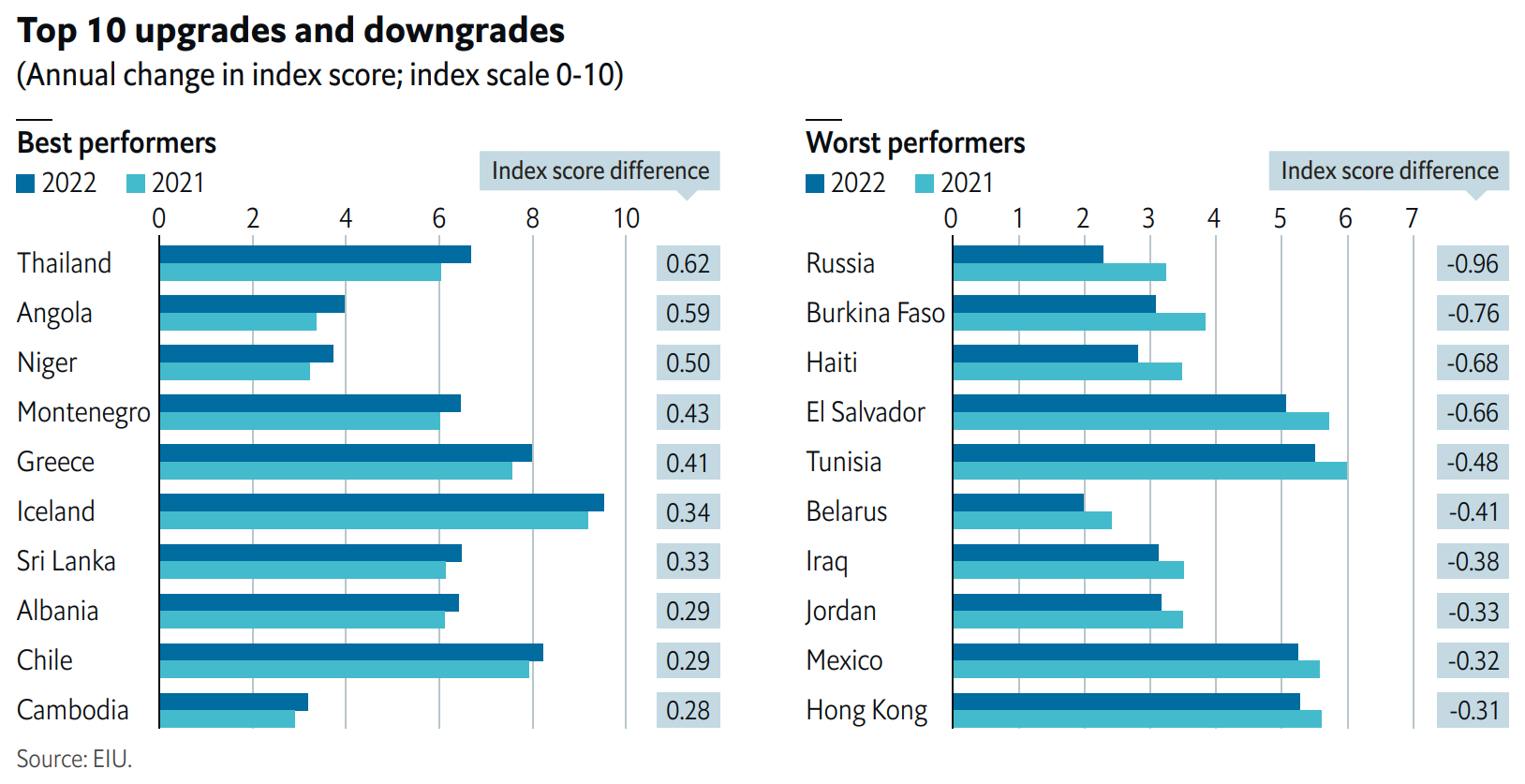

Governments around the world lifted many pandemic-related restrictions in 2022, resulting in improvements to several indicator scores across many countries, so it is striking that there was not a rebound in the index total score. The positive effect of the restoration of individual freedoms that had been temporarily curtailed by the covid-19 pandemic was cancelled out by other negative developments globally, as discussed in detail in the in-depth regional review at the back of the report. To illustrate the point, the chart on page 6 shows that the ten greatest country downgrades more than cancelled out the combined ten biggest upgrades. Overall, the positive and negative score changes globally cancelled each other out, resulting in an essentially unchanged global average score in 2022 compared with 2021. However, in the context of the rollback of pandemic-driven restrictions on individual rights in 2022, the stagnation in the global score is a disappointment.

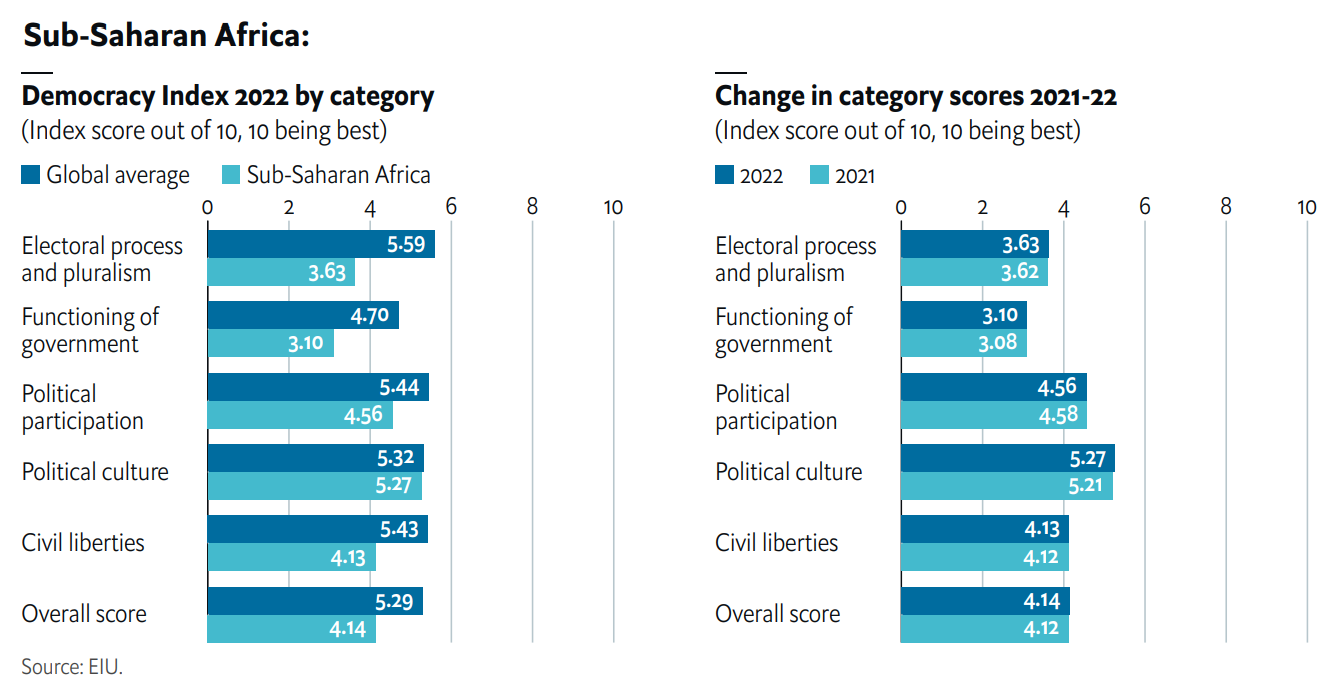

The view from the regions

The stagnation in the global score in 2022 is mirrored, as one would expect, in the regional results. The regional average score for Asia and Australasia in 2022 remains the same as in the previous year, at 5.46. The regional averages for North America (8.37), Sub-Saharan Africa (4.14) and eastern Europe (5.39) have scarcely changed either compared with 2021, when they were 8.36, 4.12 and 5.36 respectively. Only the Middle East and North Africa records a notable overall deterioration, with its average score falling from 3.41 in 2021 to 3.34 in 2022, while Latin America and the Caribbean continues its recent decline, but at a slower pace than last year: its score falls from 5.83 in 2021 to 5.79 in 2022. Only western Europe records an emphatic improvement in its average score, which recovered from an all-time low of 8.22 in 2021 to reach 8.36 in 2022. This returns western Europe to where it was in 2019, prior to the pandemic, when it recorded a score of 8.35. However, the region, which is home to the majority of the world’s most developed democracies, continues to underperform compared with its peak score of 8.61 in 2008.

The good news is that the number of countries recording an improvement in their score (75) has risen compared with 2021, when only 47 managed to do so. However, the index scores for the other 92 countries have either stagnated (48) or declined (44) in 2022. This is a poor outcome given the scale of the upgrades to several indicators related to the restoration of individual freedoms after pandemic lockdowns and other measures were lifted in 2022. The results suggest that the rollback of these measures did not always mean a return to the status quo ante.

The biggest improvers and the worst downgrades

There were impressive democratic gains in some countries, but also some dramatic declines. Thailand recorded the biggest overall score improvement in 2022, increasing its total from 6.04 in 2021 to 6.67. Other big improvers were Angola and Niger, from a low base in the “authoritarian regime” category, and Montenegro and Greece, which are both classified as “flawed democracies”. Having improved its score by 0.41 points, Greece is now close to being reclassified as a “full democracy”.

Foremost among the countries that performed poorly in 2022 was Russia, which had the biggest deterioration in score of any country in the world. Russia’s score dropped by 0.96 points to 2.28 from 3.24 in 2021 and its global ranking fell from 124th (out of 167) to 146th, close to the bottom of the global rankings. Belarus, whose president Alyaksandar Lukashenka is closely allied with his Russian counterpart, also suffered a sharp fall in its Democracy Index score. Other countries that registered a sharp decline in their index scores, also from a low base, included Burkina Faso in west Africa, where an Islamist insurgency has resulted in the state losing control of vast swathes of territory, the displacement of about 1.7m people and the deaths of thousands. Haiti, the poorest country in the western hemisphere, appears to be in a state of internal dissolution, as the authorities have lost control completely. Several countries in Latin America, including El Salvador and Mexico, register big negative changes in their scores in 2022. In the Middle East and North Africa, the worst-performing region in terms of its absolute score and its year-on-year score change, Tunisia, Iraq and Jordan all register sharp declines in their scores.

In keeping with the overall theme of inertia and stagnation, there are only five changes of regime category in the 2022 Democracy Index, three positive and two negative. In terms of upgrades, Chile, France and Spain return to the “full democracy” category, mainly because of a reversal of pandemic measures that had infringed citizens’ freedoms in 2020-21. Two countries, Papua New Guinea and Peru, have been downgraded, both from a “flawed democracy” classification to that of a “hybrid regime”. As a consequence of these changes, the number of “full democracies” increases from 21 in 2021 to 24 in 2022, while the number of “flawed democracies” falls from 53 to 48 and the number of “hybrid regimes” increases from 34 to 36. The number of “authoritarian regimes” remains the same, at 59.

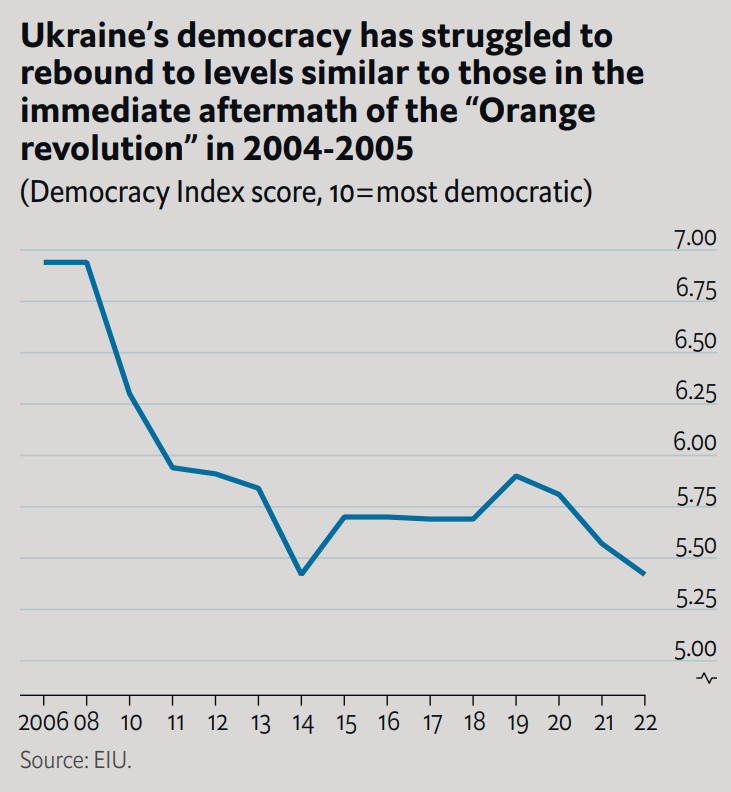

Ukraine’s example for democracy

A focus of this year’s Democracy Index report is Russia’s war in Ukraine and its importance for the future of democracy in Europe and globally. The commitment of the Ukrainian people to fight for the right to decide their own future is inspiring. It shows the power of democratic ideas and principles to bind together a nation and its people in the pursuit of democracy. If it was not immediately possible to identify a coherent Ukrainian national identity at the time of the Maidan protests in 2014, when the country was still divided between west and east, in 2022 Ukraine’s fightback against Russian domination has strengthened national sentiment and demonstrated the incontrovertibility of Ukrainian nationhood. We consider the links between national sovereignty and democracy in our special essay in section two of the report.

Russia: the biggest loser in 2022

If Ukraine’s fight to defend its borders is a demonstration of democracy in action, Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty is the product of an imperial mindset (an “empire state of mind”). Vladimir Putin’s dream of restoring Russia’s position as an imperial power is foundering. After more than ten months of fighting in Ukraine, it was clear by the end of 2022 that Russia was not only losing on the battlefield, but also struggling to win the propaganda war at home and abroad. Its bungled military campaign was provoking criticism from diehard nationalists, while the high death toll and the regime’s clumsy mobilisation were bringing the war home to ordinary Russians and unsettling them. A corollary of the war has been a pronounced increase in state repression against all forms of dissent and a further personalisation of power, pushing Russia towards outright dictatorship. Russia recorded the biggest annual fall in its index score of any country in the world in 2022 and dropped further down the global rankings.

Room at the top: the Nordics and Europe dominate

The Nordics (Norway, Finland, Sweden, Iceland and Denmark) dominate the top tier of the Democracy Index rankings, taking five of the top six spots, with New Zealand claiming second place. Norway remains the top-ranked country in the Democracy Index, thanks to its high scores across all five categories of the index, especially electoral process and pluralism, political culture, and political participation. Countries in western Europe account for eight of the top ten places in the global democracy rankings and more than half (14) of the 24 nations classified as “full democracies”. Western Europe was also the best-performing region in 2022 in terms of the increase in its index score, which rebounded to pre-pandemic levels after the lifting of coronavirus-related restrictions.

The best and the worst of 2022: upgrades, downgrades, and regime changes

Unsurprisingly in a year characterised by inertia in the Democracy Index global score, there are few changes in regime classification in 2022—five, compared with 13 in 2021. Chile, France, and Spain move up to the “full democracy” category, while Papua New Guinea and Peru have been downgraded from “flawed democracies” to “hybrid regimes”. These countries are not the best and worst performers in terms of their score changes, however. Thailand tops the world for the biggest score increase (+0.62), as the space for the political opposition opened up and the insurgency threat to the country receded. At the opposite end of the spectrum, close behind Russia (-0.96) in terms of score regressions, are Burkina Faso (-0.76), Haiti (-0.68) and El Salvador (-0.66). The African country experienced a coup at the start of the year as the democratically-elected president was overthrown as a result of growing dissatisfaction with the regime’s inability to contain an Islamist insurgency, and nine months later the coup leader was himself overthrown in another coup, for similar reasons. Meanwhile, Haiti descended into chaos in 2022. The government’s authority ebbed away as it ceded ground to armed gangs, many linked to drug trafficking networks. The prime minister’s plea for foreign intervention to re-establish order symbolised the loss of state control over the country. A failure to call elections led to significant score downgrades. In El Salvador, democratic backsliding under the president, Nayib Bukele, has led to a big downgrade in the country’s index score. The president undermined checks and balances, flouted constitutional limits by saying he will run for consecutive re-election, and introduced a State of Emergency that curbed civil liberties and criminal measures that threaten media freedoms.

Drug traffickers, insurgents, warlords, cyber hackers and other threats to sovereignty and democracy

Threats to national sovereignty come not only from invading armies such as Russia’s, but also from non-state actors such as drug-trafficking groups, private armies, Islamist and other insurgencies, and hackers committing cyber-attacks. Powerful drug cartels in Latin America and the Caribbean challenge state control over territory and are corrosive of national institutions, as well as threatening the security of ordinary citizens. This problem has exacerbated already high levels of corruption in the region and is eroding democratic norms in many countries. In many parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, especially the Sahel and west Africa, the writ of the state no longer runs across the country as militant Islamist groups establish control over territory and terrorise the inhabitants. This power vacuum has sometimes resulted in outside powers, often former colonial powers, providing military and other assistance to governments. It has also resulted in private armies, whether indigenous or external such as the Russian Wagner Group, becoming involved in the country’s internal affairs. Another increasing threat to state sovereignty and control is the proliferation of cyberattacks, either by private criminal enterprises or individuals or by hostile state actors. There were many examples of all these forms of subversion in 2022. [more]