UN: Inadequate progress on climate action makes rapid transformation of societies only option – “It is a tall, and some would say impossible, order to reform the global economy and almost halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, but we must try”

NAIROBI, 27 October 2022 – As intensifying climate impacts across the globe hammer home the message that greenhouse gas emissions must fall rapidly, a new UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report finds that the international community is still falling far short of the Paris goals, with no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place.

However, the Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window – Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies [pdf] finds that urgent sector and system-wide transformations – in the electricity supply, industry, transport and buildings sectors, and the food and financial systems – would help to avoid climate disaster.

“This report tells us in cold scientific terms what nature has been telling us, all year, through deadly floods, storms and raging fires: we have to stop filling our atmosphere with greenhouse gases, and stop doing it fast,” said Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP. “We had our chance to make incremental changes, but that time is over. Only a root-and-branch transformation of our economies and societies can save us from accelerating climate disaster.”

- Climate pledges leave the world on track for a temperature rise of 2.4-2.6°C by the end of this century

- Updated pledges since COP26 in Glasgow take less than one per cent off projected 2030 greenhouse gas emissions; 45 per cent is needed for limiting global warming to 1.5°C

- Transforming the electricity supply, industry, transport and buildings sectors, and the food and financial systems would help put world on a path to success

A wasted year

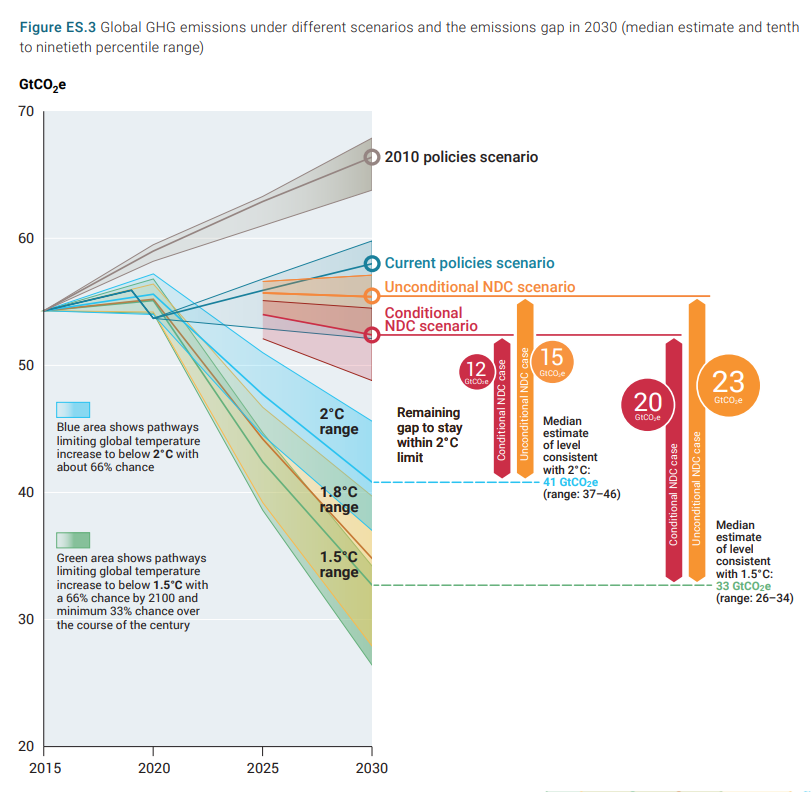

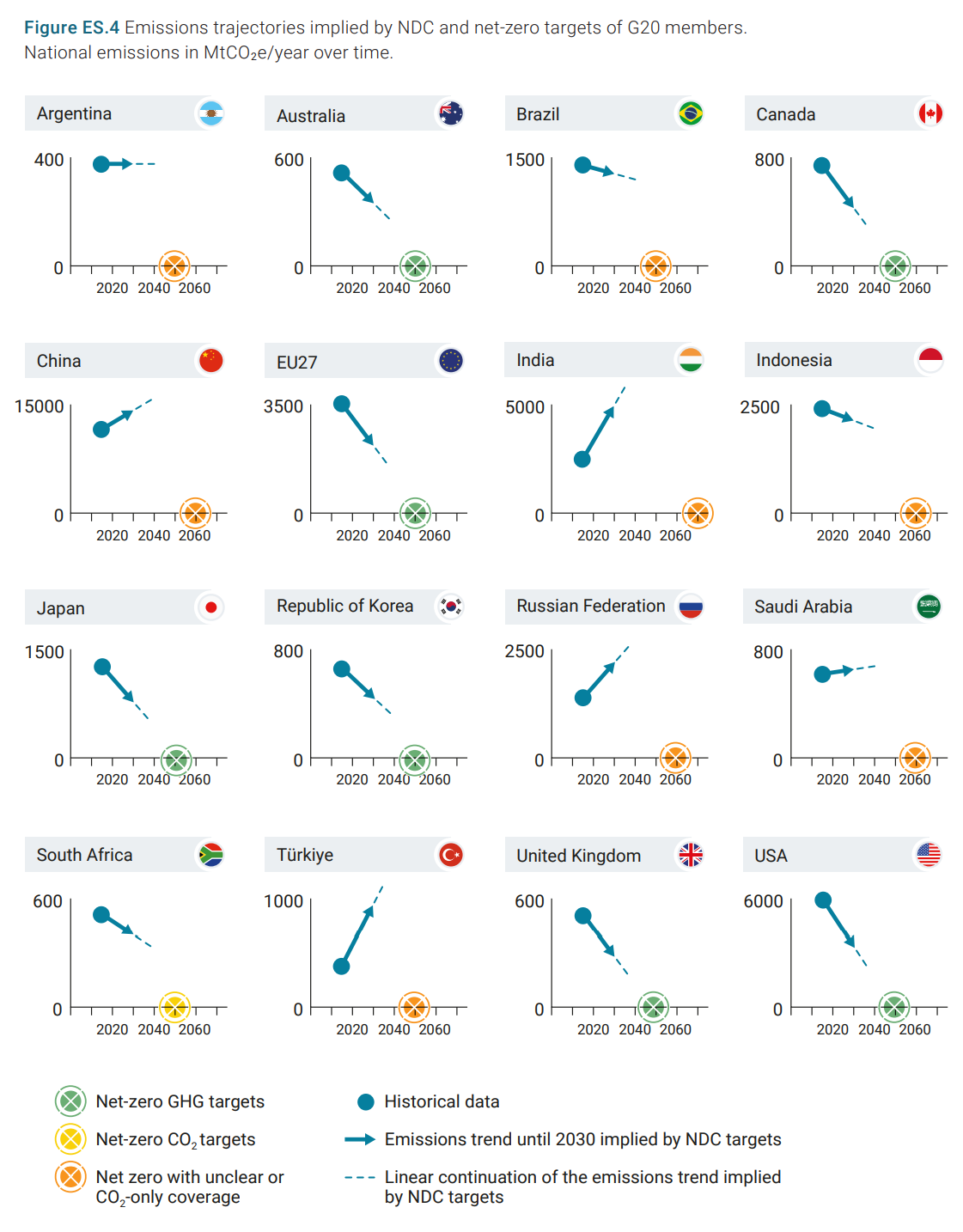

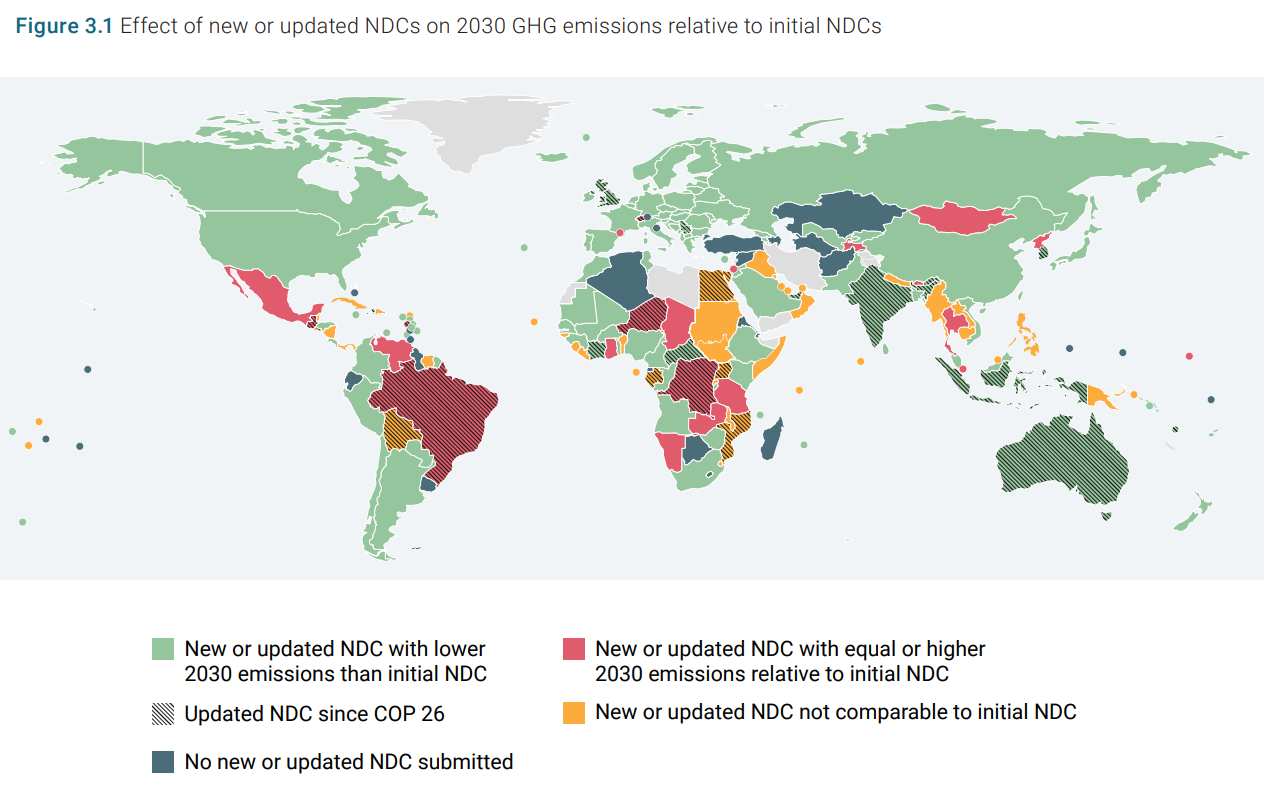

The report finds that, despite a decision by all countries at the 2021 climate summit in Glasgow, UK (COP26) to strengthen Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and some updates from nations, progress has been woefully inadequate. NDCs submitted this year take only 0.5 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent, less than one per cent, off projected global emissions in 2030.

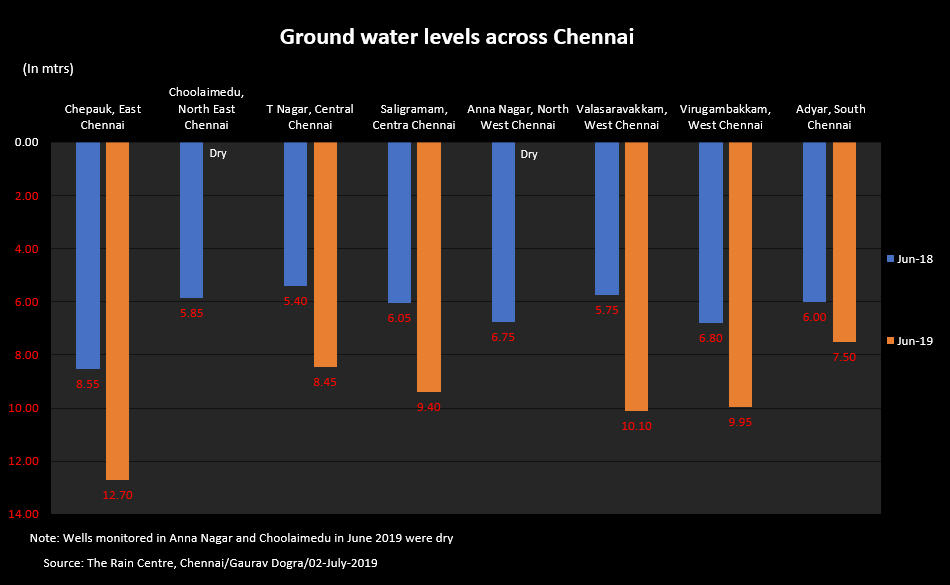

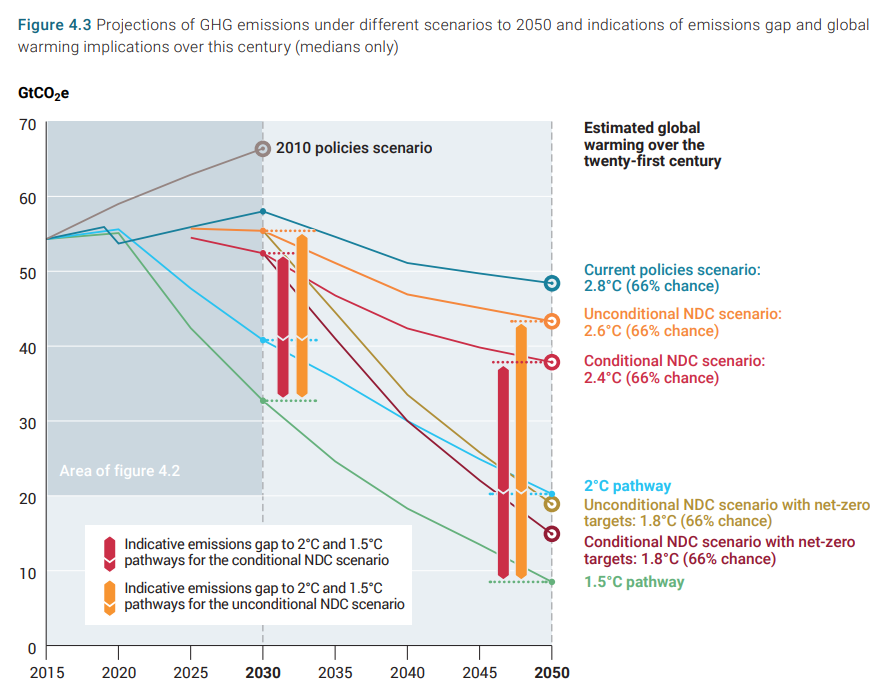

This lack of progress leaves the world hurtling towards a temperature rise far above the Paris Agreement goal of well below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C. Unconditional NDCs are estimated to give a 66 per cent chance of limiting global warming to about 2.6°C over the century. For conditional NDCs, those that are dependent on external support, this figure is reduced to 2.4°C. Current policies alone would lead to a 2.8°C hike, highlighting the temperature implications of the gap between promises and action.

In the best-case scenario, full implementation of unconditional NDCs and additional net-zero emissions commitments point to only a 1.8°C increase, so there is hope. However, this scenario is not currently credible based on the discrepancy between current emissions, short-term NDC targets and long-term net-zero targets.

Unprecedented cuts needed

To meet the Paris Agreement goals, the world needs to reduce greenhouse gases by unprecedented levels over the next eight years.

Unconditional and conditional NDCs are estimated to reduce global emissions in 2030 by 5 and 10 per cent respectively, compared with emissions based on policies currently in place. To get on a least-cost pathway to holding global warming to 1.5°C, emissions must fall by 45 per cent over those envisaged under current policies by 2030. For the 2°C target, a 30 per cent cut is needed.

Such massive cuts mean that we need a large-scale, rapid and systemic transformation. The report explores how to deliver part of this transformation in key sectors and systems.

“It is a tall, and some would say impossible, order to reform the global economy and almost halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, but we must try,” said Andersen. “Every fraction of a degree matters: to vulnerable communities, to species and ecosystems, and to every one of us.”

“Even if we don’t meet our 2030 goals, we must strive to get as close as possible to 1.5°C. This means setting up the foundations of a net-zero future: one that will allow us to bring down temperature overshoots and deliver many other social and environmental benefits, like clean air, green jobs and universal energy access.”

Electricity, industry, transport, and buildings

The report finds that the transformation towards net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in electricity supply, industry, transportation and buildings is underway, but needs to move much faster. Electricity supply is most advanced, as the costs of renewable electricity have reduced dramatically. However, the pace of change must increase alongside measures to ensure a just transition and universal energy access.

For buildings, the best available technologies need to be rapidly applied. For industry and transport, zero emission technology needs to be further developed and deployed. To advance the transformation, all sectors need to avoid lock in of new fossil fuel-intensive infrastructure, advance zero-carbon technology and apply it, and pursue behavioural changes.

Food systems can reform to deliver rapid and lasting cuts

Focus areas for food systems, which account for about a third of greenhouse gas emissions, include protection of natural ecosystems, demand-side dietary changes, improvements in food production at the farm level and decarbonization of food supply chains. Action in these four areas can reduce projected 2050 food system emissions to around a third of current levels, as opposed to emissions almost doubling if current practices are continued.

Governments can facilitate transformation by reforming subsidies and tax schemes. The private sector can reduce food loss and waste, use renewable energy and develop novel foods that cut down carbon emissions. Individual citizens can change their lifestyles to consume food for environmental sustainability and carbon reduction, which will also bring many health benefits.

The financial system must enable the transformation

A global transformation to a low-emissions economy is expected to require investments of at least USD 4-6 trillion a year. This is a relatively small (1.5-2 per cent) share of total financial assets managed, but significant (20-28 per cent) in terms of additional annual resources to be allocated.

Most financial actors, despite stated intentions, have shown limited action on climate mitigation because of short-term interests, conflicting objectives and not recognizing climate risks adequately.

Governments and key financial actors will need to steer credibly in one direction: a transformation of the financial system and its structures and processes, engaging governments, central banks, commercial banks, institutional investors and other financial actors.

The report recommends six approaches to financial sector reform, which must be carried out simultaneously:

- Make financial markets more efficient, including through taxonomies and transparency.

- Introduce carbon pricing, such as taxes or cap-and-trade systems.

- Nudge financial behaviour, through public policy interventions, taxes, spending and regulations.

- Create markets for low-carbon technology, through shifting financial flows, stimulating innovation and helping to set standards.

- Mobilize central banks: central banks are increasingly interested in addressing the climate crisis, but more concrete action on regulations is needed.

- Set up climate “clubs” of cooperating countries, cross-border finance initiatives and just transformation partnerships, which can alter policy norms and change the course of finance through credible financial commitment devices, such as sovereign guarantees.

Contact

- Keisha Rukikaire, Head of News & Media, UN Environment Programme

Inadequate progress on climate action makes rapid transformation of societies only option – UN