Villagers accuse city of seizing water as drought parches “India’s Detroit” – “Private tankers have fitted more than eight bore wells in our village and are indiscriminately extracting thousands of liters of water every day”

By Sudarshan Varadhan

2 July 2019

CHENNAI (Reuters) – In the small village of Bangarampettai, 20 miles from India’s manufacturing capital Chennai, about 150 people last month “captured” a water tanker, breaking its windscreen and deflating its tires before handing it over to a nearby police station.

People living on the outskirts of this southern Indian metropolis are blocking roads and laying siege to tanker lorries because they fear their water reserves are being sacrificed so city dwellers, businesses and luxury hotels don’t run out.

“Private tankers have fitted more than eight bore wells in our village and are indiscriminately extracting thousands of liters of water every day,” the Bangarampettai villagers wrote in a letter to a government official in the region a day after they stopped the tanker.

Bad water management and a lack of rainfall mean that all four reservoirs that supply Chennai, a carmaking center dubbed “India’s Detroit”, have run virtually dry this summer. That has forced some schools to shut, companies to ask employees to work from home and hotels to ration water for guests.

Other Indian cities, including the capital New Delhi and technology hub Bengaluru, are also grappling with serious water shortages.

But the problem is most acute in Chennai, where local tensions have been inflamed by the Tamil Nadu state government tapping wells normally used for agriculture and villagers’ daily needs.

In their letter, the Bangarampettai residents said they had petitioned government officials, including the district’s top administrator, several times, but the tankers keep returning. “We don’t have water in one of the two water tanks in the village now because the private tankers have been extracting water day and night,” said S Arul, a local signboard painter.

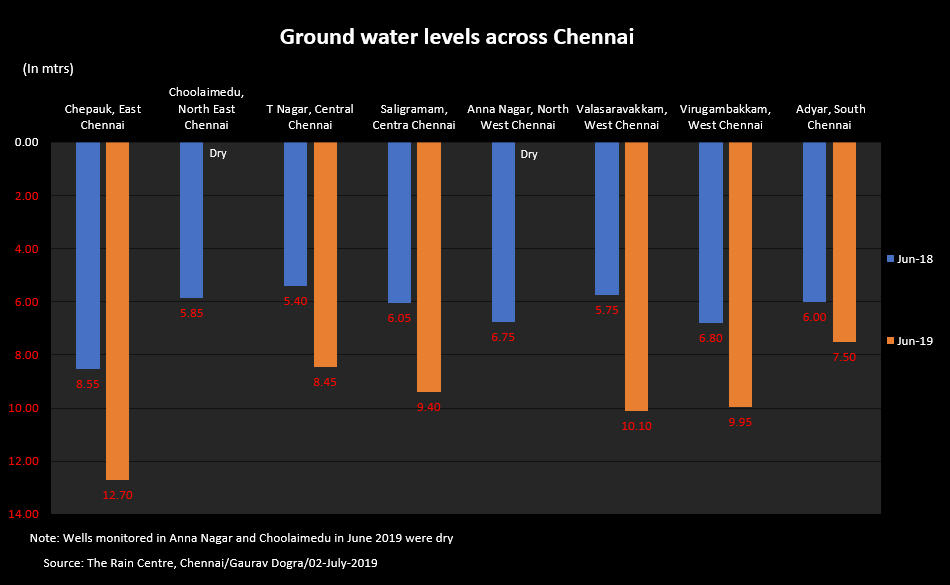

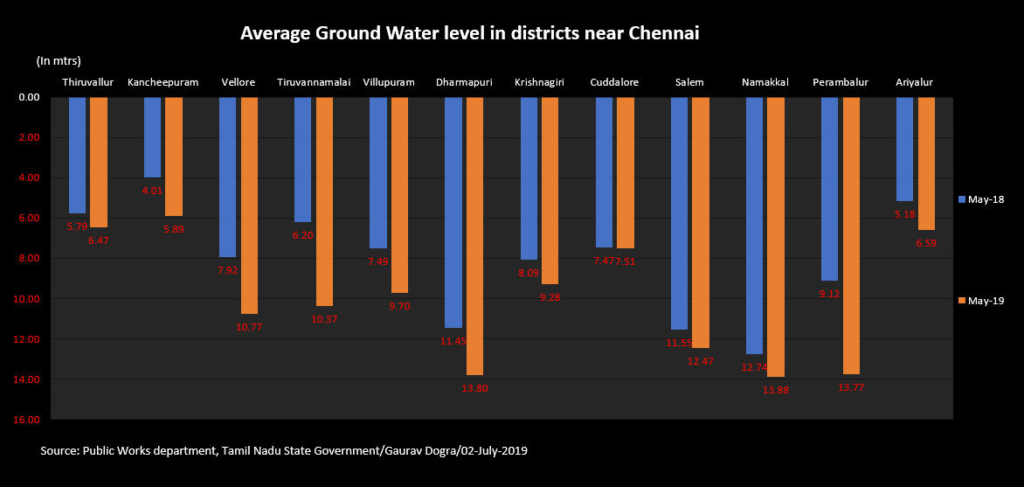

Groundwater levels in Chennai’s neighboring districts, Thiruvallur and Kancheepuram, fell at a faster rate in May than the state average in districts excluding Chennai, data from the state’s public works department showed. Data for Chennai district has not been made public. The Kancheepuram district to the southeast of the city, which includes the factories of many foreign automakers, saw groundwater levels deplete more than 6 ft (1.88 meters), or three times the state average, to about 20 ft during the year ended May 2019, the data showed.

There is no sign yet that the factories are having to reduce production because of the shortage.

M Jeeva, 27, who runs a hardware store near Bangarampettai, said he followed trucks taking the village’s water back into the city and found they mostly supply hotels and companies.

Two of the biggest lakes in Thiruninravur, the nearest town to Bangarampettai, are dry. When Reuters visited, a fishing boat could be seen grounded and abandoned while children played cricket in the middle of the dry lakebed. […]

Like many Indian cities, Chennai’s growth over the past 20 years has been rapid and haphazard. Its population will have likely more than doubled to 10.7 million by 2020, from 4.6 million in 2011, according to the United Nations. [more]

Villagers accuse city of seizing water as drought parches ‘India’s Detroit’