Groundwater resources are drying up across the globe – “Climate variability and change can impact water supplies underground as well as above-ground”

By Matthew Rozsa

24 January 2024

(Salon) – Humans rely on groundwater for many things, but especially our food. Roughly 30 percent of all the planet’s available freshwater comes from groundwater, or water that is found underground in the spaces between rocks, soil and sand. It is primarily used for agriculture and billions of humans are dependent on it, facing severe food deprivation without it. A study published this month in Nature Water even details how aquifer depletion also makes it harder to resist historic droughts, such as the record-breaking dry spells unleashed by climate change.

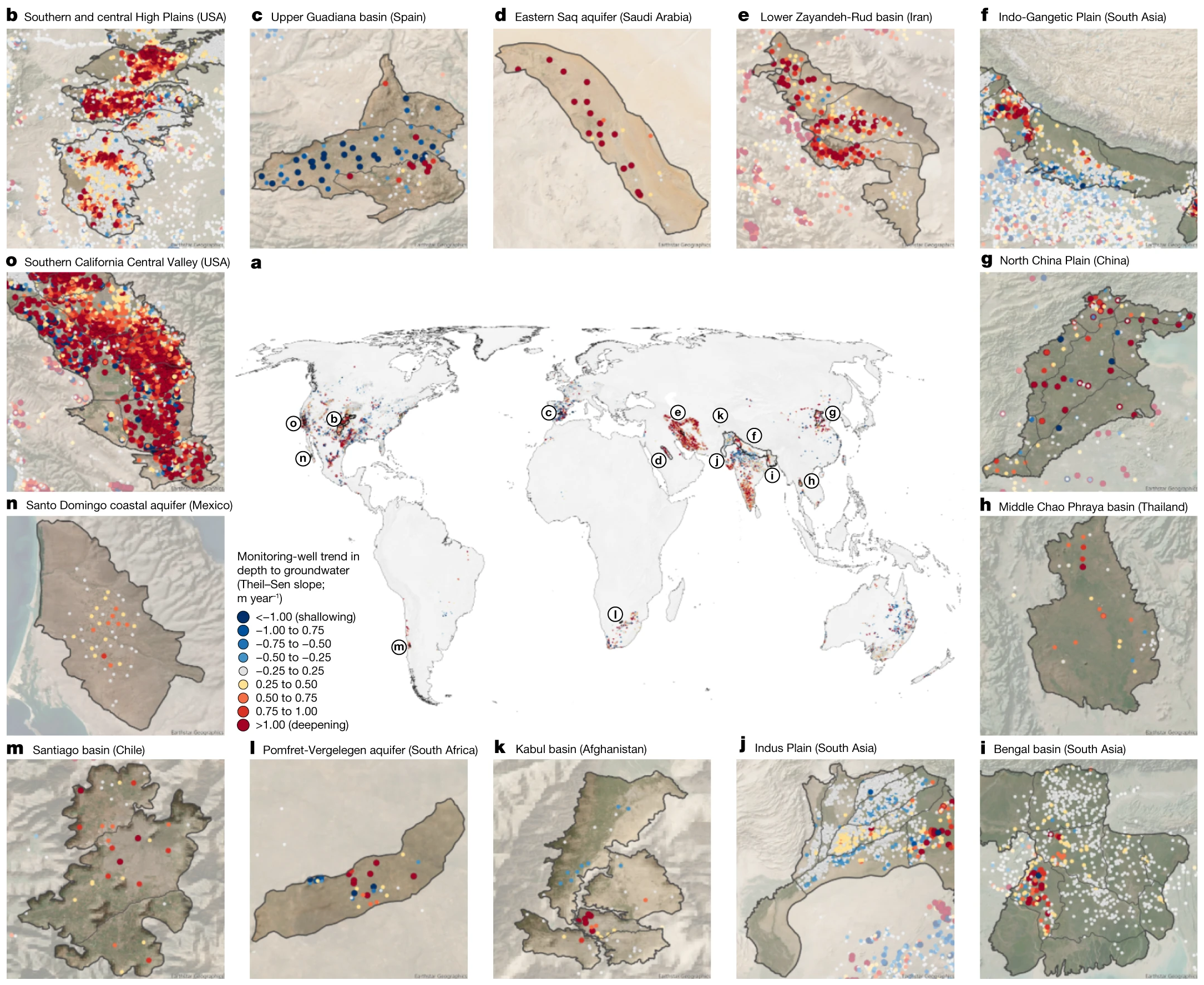

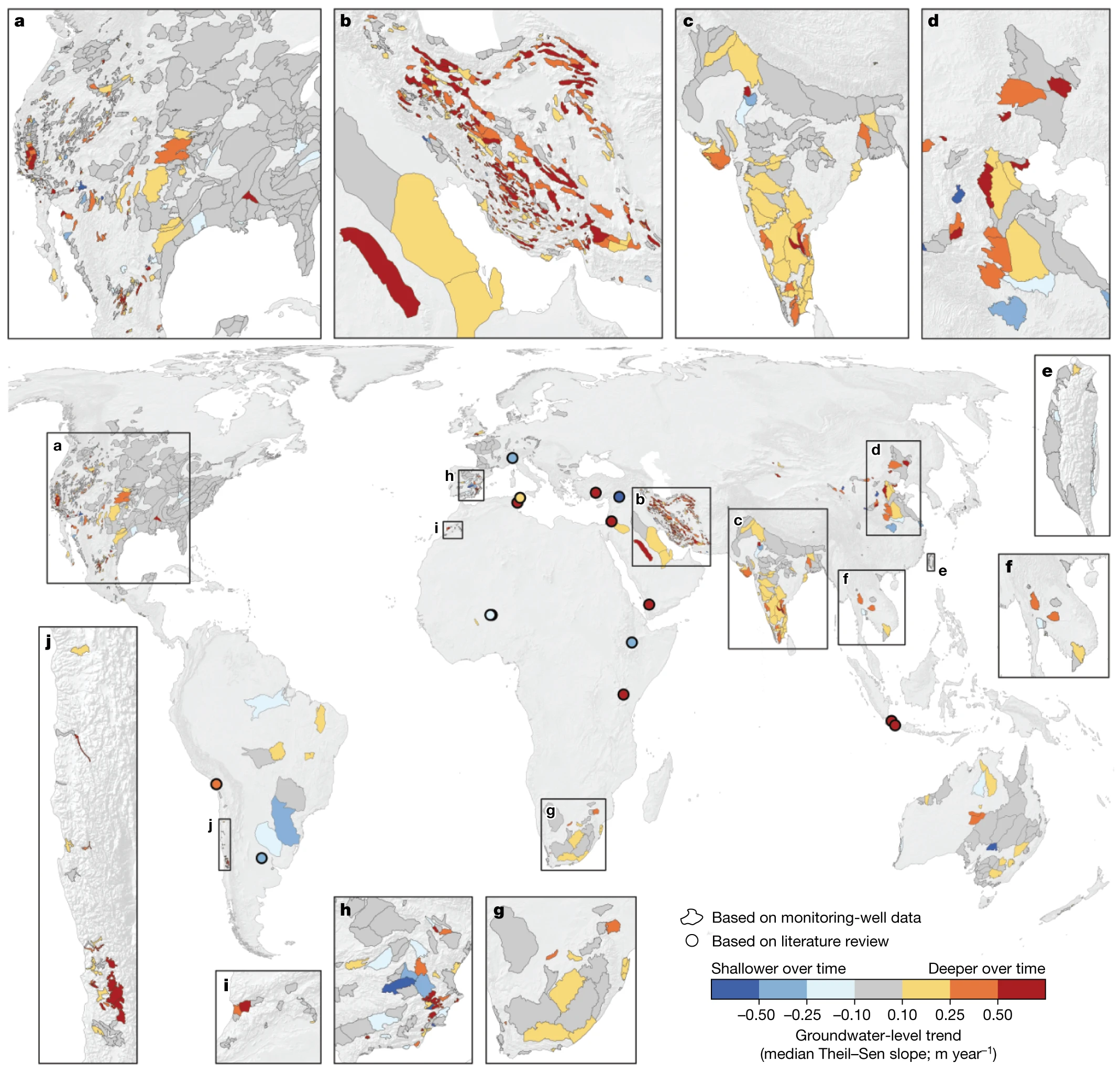

Which makes it pretty alarming that groundwater levels are dropping across the globe, often at increasing rates, as new research in the journal Nature have now estimated the full scope of the problem: Groundwater is on the decline in 71% of the aquifers studied.

The scientists from the University of California, Santa Barbara reviewed nearly 1,700 aquifers all over the planet, including national and subnational records over a century including 300 million water level measurements from 1.5 million wells. Among other things, they learned that rates of groundwater declined aggressively started in the 1980s and 1990s, then became even worse from 2000 to the present. One statistic stands out: The accelerating rates of decline occurred at almost three times the pace that would have happened in the same number of locations if it had occurred by chance.

“We demonstrate that most of the places with accelerated groundwater level declines also had declining rainfall over time,” co-author Dr. Scott Jasechko at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management at the University of California, Santa Barbara told Salon by email. “This finding demonstrates that climate variability and change can impact water supplies underground as well as above-ground.”

Jasechko identified a variable in addition to climate change that is causing the groundwater depletion.

“Groundwater is vital to global irrigated agriculture,” Jasechko pointed out. “There are places where groundwater pumping for irrigation, to support food production, is leading to groundwater depletion. Our work highlights some relatively rare cases where groundwater depletion has been addressed via interventions, including policy changes and water engineering.”

He later added, “Groundwater depletion is a threat to global irrigation. Addressing the groundwater problem can help secure future food production.” […]

Other research has also painted an alarming picture of human groundwater use. A 2023 study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters found that a tremendous amount of groundwater has been extracted from beneath our feet — more than 2 trillion tons of groundwater between 1993 and 2010, in fact — and that as a result the True North Pole has shifted at a rate of 4.36 centimeters per year (or more than 1.7 inches). […]

As groundwater depletion demonstrates, humans are radically altering our home planet through climate change. Our reliance on groundwater presents a vulnerability for our species, one that could lead to massive suffering in our species’ future, especially if we manage it irresponsibly — all while our overheating planet exacerbates the problem. [more]

Groundwater resources are drying up across the globe. New research suggests we can fight the drip

Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally

ABSTRACT: Groundwater resources are vital to ecosystems and livelihoods. Excessive groundwater withdrawals can cause groundwater levels to decline1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, resulting in seawater intrusion11, land subsidence12,13, streamflow depletion14,15,16 and wells running dry17. However, the global pace and prevalence of local groundwater declines are poorly constrained, because in situ groundwater levels have not been synthesized at the global scale. Here we analyse in situ groundwater-level trends for 170,000 monitoring wells and 1,693 aquifer systems in countries that encompass approximately 75% of global groundwater withdrawals18. We show that rapid groundwater-level declines (>0.5 m year−1) are widespread in the twenty-first century, especially in dry regions with extensive croplands. Critically, we also show that groundwater-level declines have accelerated over the past four decades in 30% of the world’s regional aquifers. This widespread acceleration in groundwater-level deepening highlights an urgent need for more effective measures to address groundwater depletion. Our analysis also reveals specific cases in which depletion trends have reversed following policy changes, managed aquifer recharge and surface-water diversions, demonstrating the potential for depleted aquifer systems to recover.

Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally