Impacts for half of the world’s mining areas are undocumented – 56 percent of global mining areas visible from satellite images have no production information available

By Victor Maus and Tim T. Werner

3 January 2024

(Nature) – Mining is a crucial industry — from iron and copper to gravel and sand, we depend on it for the basic building blocks of the modern world. It is a fast changing sector, as the clean energy transition and digitalization boost demand for materials such as cobalt and lithium and curb the need for others, such as fossil fuels. Yet we know surprisingly little about what’s going on in the sector globally and how mining affects the environment and communities near mines.

Much of what we do know isn’t good. Climate change isn’t the only problem associated with coal mining, for example1. In Indonesia, the world’s biggest coal exporter, rainforests are being cleared for coal mines and these mines pose safety risks — since 2011, more than 40 people, mostly children, have drowned in poorly managed coal pits2,3. The demand for materials, and the rush for lithium in particular — which is used in batteries for electric vehicles — is raising concerns that the global appetite for energy is coming at too great a cost. In 2022, in Serbia, for example, massive protests over fears of habitat destruction and toxic-waste spills led to licences being revoked for a proposed lithium mine.

Because no mine is immune from risk or controversy, independent research is essential to decipher the extent of its risks and impacts and to build trust with the public. However, enormous data gaps prevent this. There’s no comprehensive inventory of the world’s hundreds of thousands of mine sites and exploration zones. Publicly available data on mine production, waste, pollution and consumption of water and energy are widely lacking. A large share of global mineral production might be illegal — for example, more than 80% of gold mined in Colombia and Venezuela comes from illegal operations, according to the United Nations Environment Programme4.

These gaps leave researchers with a fragmented view of the industry and hamper their ability to track decarbonization strategies and inform policies and decision-making.

Whether it is coal for business-as-usual, lithium for batteries, cobalt for smartphones or neodymium for wind turbines, all future pathways require mining, and at a cost. We can’t manage what we can’t measure, and so it’s time to address the ‘known unknowns’ of the mining sector. Here, we propose four key steps.

Spotlight the weaknesses in mining data

First, researchers must be frank about the information they are dealing with. Global mining studies rely largely on data contained in company reports. Compilations exist, such as the S&P Capital IQ Pro database, which is the basis of nearly all worldwide assessments published in the field. But this database sits behind a paywall and is incomplete.

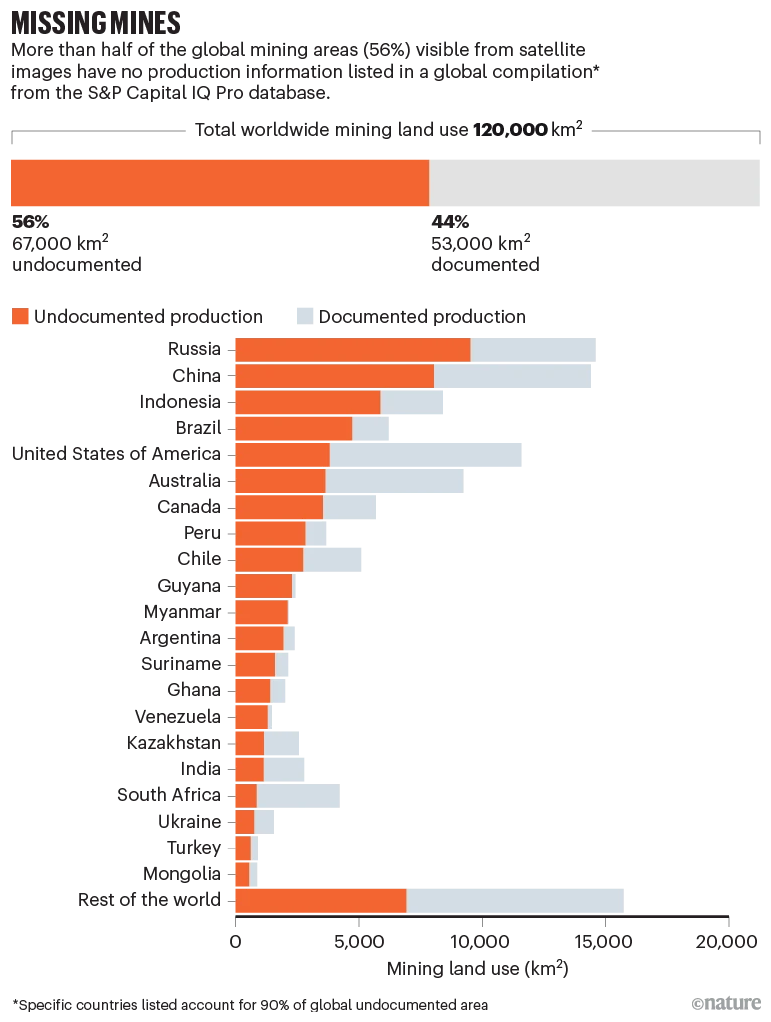

For example, after combing almost 120,000 square kilometres of mining areas identified globally using satellite images5,6, we found that only 44% of the mines we detected had production information noted in the S&P database (see ‘Missing mines’). There is no pattern to the gaps — data are missing for all types of commodity and locality and for all sorts of reasons, from scant reporting to illegal activities, as inferred from satellite images and other sources of information. Historic and abandoned sites are typically unrecorded. And the job of finding and compiling data from company websites and reports is too vast to complete.

Researchers persist in using the S&P database — it’s often the only choice available. But few acknowledge, let alone attempt to account for, the limitations and biases within it. Common types of analysis make gross oversimplifications. For example, risks are often inferred from mine locations alone, and by assuming that the intensity of mining is the same worldwide7,8. Yet, treating mines as dots on a map doesn’t account for differences in the scale of impact between sites. An underground shaft opening will lead to different types of damage compared with open-pit excavations and waste-disposal areas.

What should researchers do? At a minimum, until more data are available, we suggest that global mining studies should include statements of data bias and completeness. These might include: the extent of potential unofficial mining and commodity trading in a study area, based on media reporting and national accounts. They might state whether sample bias can be quantified or results tailored to reflect it, and how the absence of site-specific data affects results in a sample. Statements should report the extent to which official statistics or data compilations are complete, and whether any other corporate factors might contribute to reporting bias.

Such statements will not weaken the impact of research. Highlighting that the impacts are under-measured only makes the call to action louder. [more]

Impacts for half of the world’s mining areas are undocumented