Gulf of Mexico oil worse for climate than thought, study – “Expanding production in shallow waters, the way it’s been done historically, would have disproportionately high climate impacts”

By Drew Costley

3 April 2023

(AP) – Offshore oil and gas operations in the Gulf of Mexico are releasing far more climate-changing methane than official estimates show, according to a new study published Monday.

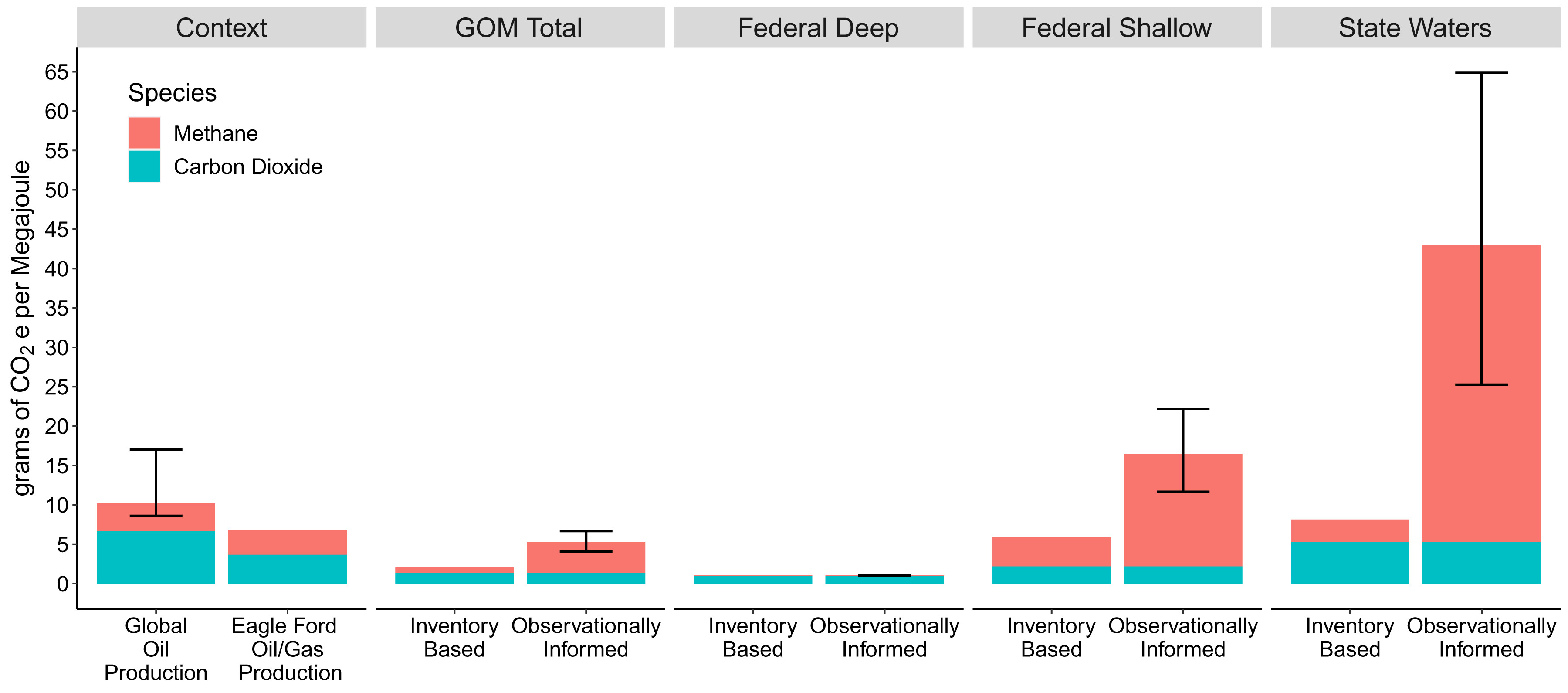

Using data collected from aircraft in part, climate scientists found the additional methane coming from oil and gas platforms in the Gulf region raises their carbon intensity — the amount of climate-changing gas per unit of energy in the fuel — to twice as much as estimated by U.S. agencies like the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. The study is published in PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Reductions in both methane and carbon dioxide emissions are essential to lessen the future severity of climate change, the study notes.

“You don’t have to travel halfway around the world to find unusually high emissions in oil and gas fields,” said Rob Jackson, a Stanford University climate scientist who was not involved in the study. “It’s happening right here in our backyards.”

Other climate scientists who were not involved in the study praised it for its approach.

“This study represents a novel and thoughtful assessment of the climate impact of oil and gas production in the Gulf of Mexico,” said Riley Duren, a research scientist at the University of Arizona who leads Carbon Mapper, a group pioneering accessible and transparent information about where greenhouse gases are being released. “In particular, the authors have demonstrated the importance of jointly quantifying methane emissions from leakage and venting and carbon dioxide emissions from combustion.”

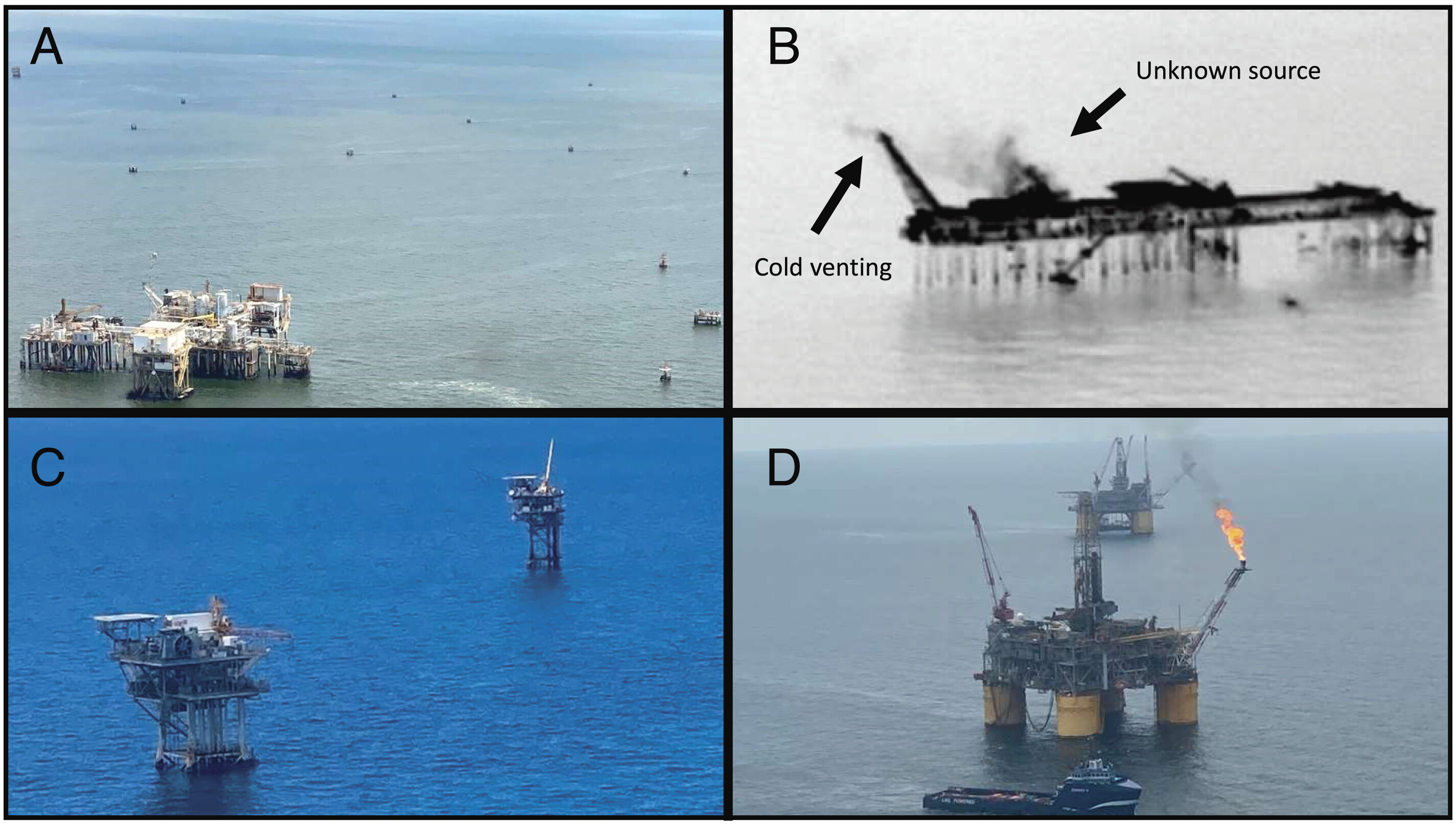

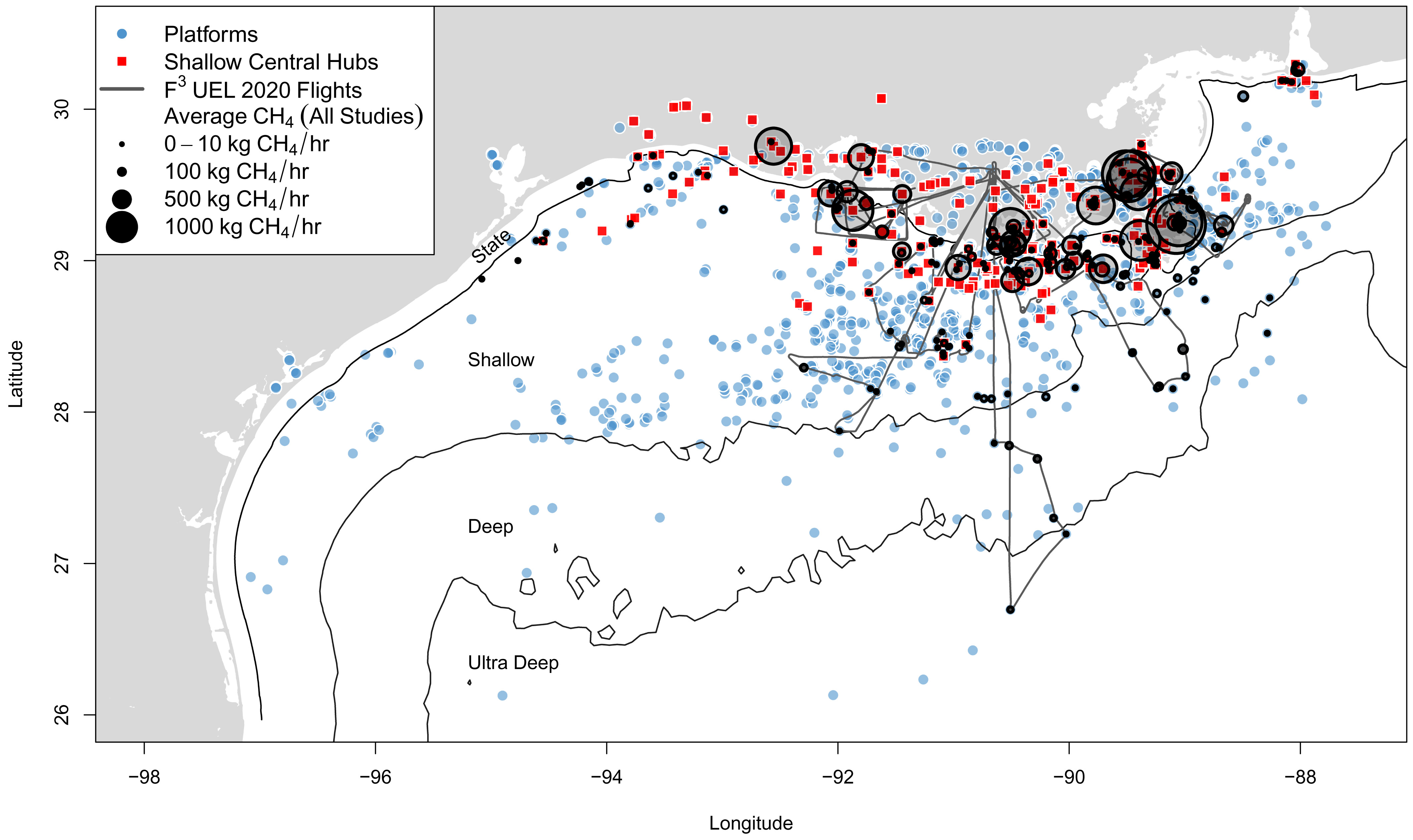

Eric A. Kort, a climate scientist at the University of Michigan and co-author of the study, said the majority of the methane emissions researchers found were wafting from oil and gas operations in shallow waters, where the oldest oil platforms are. The problem was most acute where energy companies are mostly going after oil and aren’t that interested in the methane gas that lies underground with it, so simply release it into the air.

“It was easier to build platforms in shallow water and drill in shallow waters. Now there’s opportunity to extend out into quite deep waters,” Kort said.

But this gas has a powerful effect on the climate and is responsible for a significant amount of the climate change we are already experiencing.

The oil platforms out in deeper water emitted much less methane per unit of energy.

The findings could have implications for future offshore oil and gas operations as the federal government prepares to lease more areas in the Gulf for drilling. The Inflation Reduction Act includes a provision that mandates the federal government offer extensive new offshore leases in federal water for oil and gas drilling if it wants to lease for offshore solar and wind energy.

Kort said that the findings can help policymakers or federal and state agencies compare the climate impact of shallow versus deepwater drilling, to guide where they offer leases.

“It’s very clear from our results that expanding production in shallow waters, the way it’s been done historically, would have disproportionately high climate impacts,” he said. [more]

Gulf of Mexico oil worse for climate than thought, study

Excess methane emissions from shallow water platforms elevate the carbon intensity of US Gulf of Mexico oil and gas production

ABSTRACT: The Gulf of Mexico is the largest offshore fossil fuel production basin in the United States. Decisions on expanding production in the region legally depend on assessments of the climate impact of new growth. Here, we collect airborne observations and combine them with previous surveys and inventories to estimate the climate impact of current field operations. We evaluate all major on-site greenhouse gas emissions, carbon dioxide (CO2) from combustion, and methane from losses and venting. Using these findings, we estimate the climate impact per unit of energy of produced oil and gas (the carbon intensity). We find high methane emissions (0.60 Tg/y [0.41 to 0.81, 95% confidence interval]) exceeding inventories. This elevates the average CI of the basin to 5.3 g CO2e/MJ [4.1 to 6.7] (100-y horizon) over twice the inventories. The CI across the Gulf varies, with deep water production exhibiting a low CI dominated by combustion emissions (1.1 g CO2e/MJ), while shallow federal and state waters exhibit an extraordinarily high CI (16 and 43 g CO2e/MJ) primarily driven by methane emissions from central hub facilities (intermediaries for gathering and processing). This shows that production in shallow waters, as currently operated, has outsized climate impact. To mitigate these climate impacts, methane emissions in shallow waters must be addressed through efficient flaring instead of venting and repair, refurbishment, or abandonment of poorly maintained infrastructure. We demonstrate an approach to evaluate the CI of fossil fuel production using observations, considering all direct production emissions while allocating to all fossil products.