California’s wildfire smoke plumes are unlike anything previously seen – California fire carbon emissions in 2020 exceed previous record by nearly 2 times

By Matthew Cappucci

12 September 2020

(The Washington Post) – More than 3.1 million acres have burned in California this year, part of a record fire season that still has four months to go. A suffocating cloud of smoke has veiled the West Coast for days, extending more than a thousand miles above the Pacific. And the extreme fire behavior that’s been witnessed this year hasn’t just been wild — it’s virtually unprecedented in scope and scale.

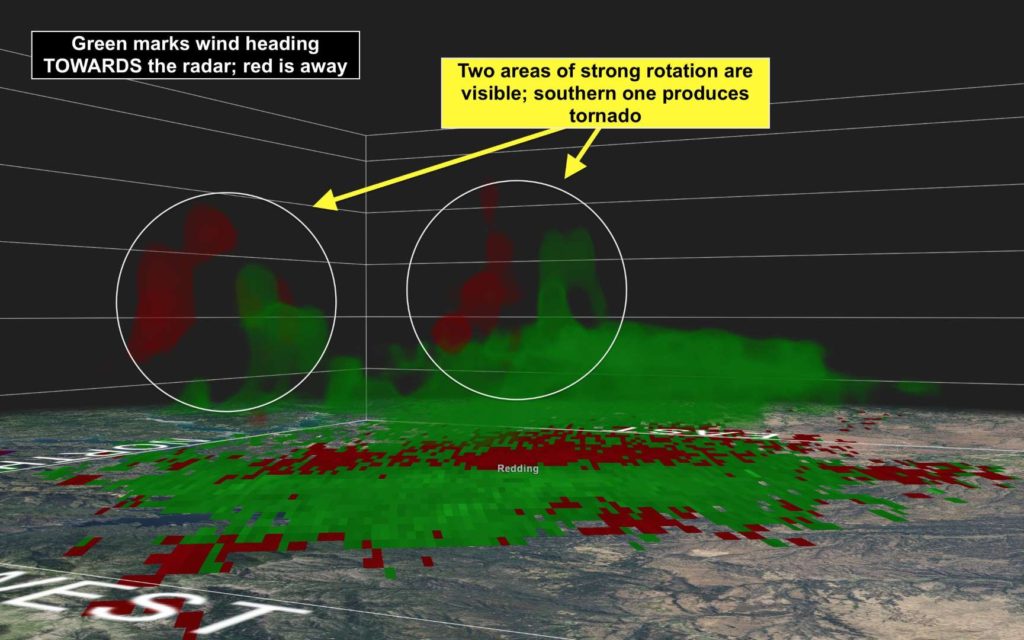

Fire tornadoes have spun up by the handful in at least three big wildfires in the past three weeks, based on radar data. Giant clouds of ash and smoke have generated lightning. Multiple fires have gone from a few acres to more than 100,000 acres in size in a day, while advancing as many as 25 miles in a single night. And wildfire plumes have soared up to 10 miles high, above the cruise altitude of commercial jets.

Scientists have been scrambling to collect as much data on these wildfires as possible, hoping to unlock the secrets to their extreme behavior and fury. Among them is Neil Lareau, a professor of atmospheric sciences in the department of physics at the University of Nevada at Reno. Lareau closely studies pyrocumulus clouds, towering explosion-like plumes of heat that develop above intense blazes.

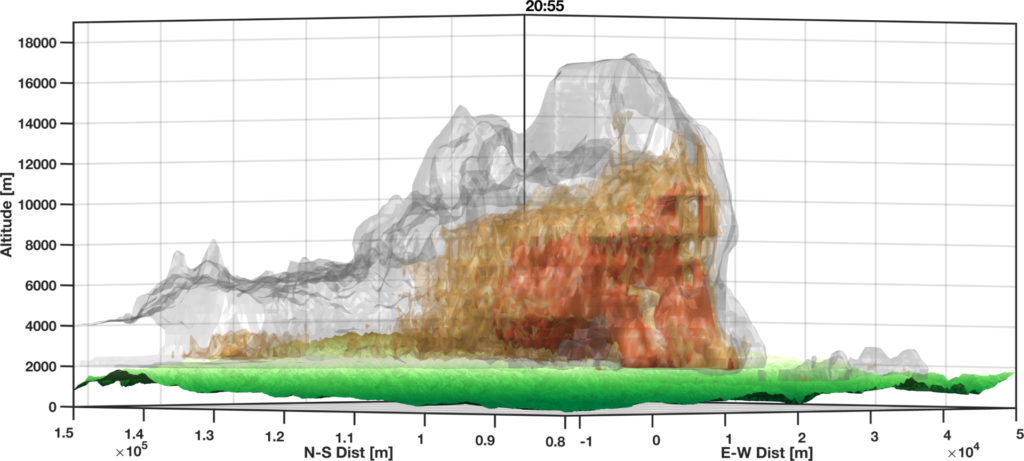

He retrieved data from the National Weather Service’s network of Doppler radars, which scan the skies every few moments at up to 15 different vertical angles. By stitching these different elevation “slices” together, he was able to produce a three-dimensional model of each smoke plume.

Wildfires and smoke plumes towering to new heights

The Creek Fire, which burned nearly 200,000 acres in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, was only 6 percent contained on Friday. On Sept. 5, a day after it was first ignited, its smoke plume soared to 55,000 feet. That’s taller than many of the tornadic thunderstorms that roll across Oklahoma and Kansas each spring.

Such clouds are both indicators of and contributors to extreme fire behavior, such as rapid fire spread, the formation of fire vortices including tornadoes, along with other dynamics that are hazardous to firefighters and can imperil communities.

“Anecdotally, this is the deepest that I’ve seen,” said Lareau, who was shocked by the height achieved by the smoke plume. “It’s about a solid 10,000 feet higher than we’re typically seeing with the highest of these plumes.”A heat wave and dry winds fuel wildfires in the West

Lareau says the extreme height is a testament to the fire’s rapid spread and release of heat.

“[That], as well as the large burning area, results in the total amount of heat being injected into the atmosphere just being tremendous,” said Lareau.

He also noted the record-shattering heat wave in California, which brought Los Angeles County’s hottest ever measured temperature of 121 degrees on Sept. 6, also played a role in the “tremendous plume depth.” [more]

California’s wildfire smoke plumes are unlike anything previously seen

Historic Fires Devastate the U.S. Pacific Coast

By Adam Voiland

12 September 2020

(NASA) – Climate and fire scientists have long anticipated that fires in the U.S. West would grow larger, more intense, and more dangerous. But even the most experienced among them have been at a loss for words in describing the scope and intensity of the fires burning in West Coast states in September 2020.

Lightning initially triggered many of the fires, but it was unusual and extreme meteorological conditions that turned some of them into the worst conflagrations in the region in decades. Record-breaking air temperatures, periods of unusually dry air, and blasts of fierce winds—on top of serious drought in some areas—led fires to ravage forests and loft vast plumes of smoke to rarely seen heights.

“We had a perfect storm of meteorological factors come together that encouraged extreme burning,” said Vincent Ambrosia, the associate program manager for wildfire research in NASA’s Earth Applied Sciences Program. “That was layered on top of shifting climate patterns—a long term drying and warming of both the air and vegetation—that is contributing to the growing trend we are seeing toward larger, higher-intensity fires in the U.S. West.”

The buildup of fuels may be another relevant factor. Human efforts to extinguish most fires over the past 120 years has led to an increase in old, overgrown forests in the West that burn intensely when they catch fire, explained Ambrosia.

The fires have proven devastating for people, property, and landscapes. With more than 3.1 million acres burned as of 11 September 2020, the fires have obliterated California’s record for the number of acres burned in a year. Six of the top 20 largest fires in state history have occurred in 2020, according to Cal Fire. Authorities attributed more than two dozen deaths to the fires; several towns in Oregon and California have been severely damaged; at least 4,000 homes have been destroyed; and hundreds of thousands of people faced evacuation orders.

The view of the fires from space has been unusual and grim. Throughout the outbreak, sensors like the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) and the Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite (OMPS) on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite have collected daily images showing expansive, thick plumes of aerosol particles blowing throughout the U.S. West on a scale that satellites and scientists rarely see.

On multiple days, OMPS measured smoke clouds over the western U.S. with higher aerosol index values than anything Colin Seftor, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, says he has ever seen with OMPS. For instance, on September 9 (image above), a frontal boundary moved into the Great Basin and produced very high downslope winds along the mountains of Washington, Oregon, and California. The winds whipped up the fires, while a pyrocumulus cloud from the Bear fire in California injected smoke high into the atmosphere. The sum of these events was an extremely think blanket of smoke along the West Coast.

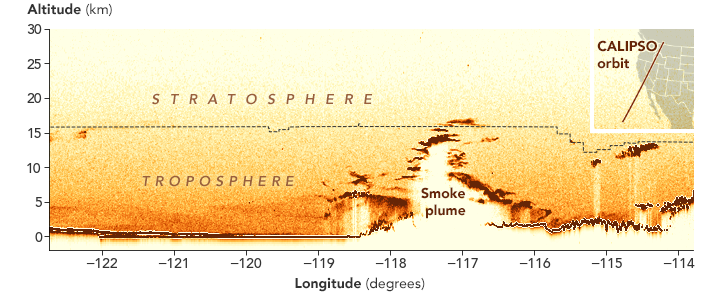

A few days earlier, on September 7 (image above), the joint NASA-CNES CALIPSO satellite observed smoke from an explosive pyrocumulus cloud that emerged from the Creek fire in California. The cloud lofted smoke 17 kilometers (10 miles) into the atmosphere, a record for a fire in North America and enough to carry smoke into the stratosphere.

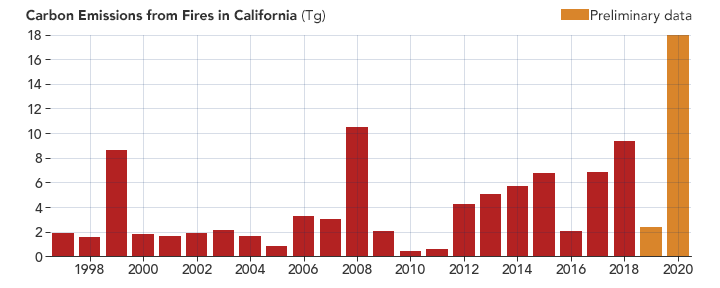

All of that smoke translates into significant carbon emissions. “By our estimates, 2020 is the highest year of fire carbon emissions for California in our Global Fire Emissions Database, which has data for 1997 to the present,” said Douglas Morton, chief of the biospheric sciences laboratory at NASA Goddard. “Fire emissions this year far outpace the annual totals for all other years, and it is only September 11.”

NASA scientists plan to use this unusual event to test and potentially improve models and forecasts of the dispersion of smoke. “The multiple CALIPSO overpasses over California in the past few weeks will provide a unique set of observations to validate retrospective fire plume simulations; they also could make huge difference in near-real-time applications,” explained John-Paul Vernier, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Applied Sciences Disasters program. “With state-of-the-art satellite observations from CALIPSO, MISR, and MODIS, we are doing everything we can to improve air quality forecasts.”