World’s supply of fresh water in trouble as mountain ice vanishes – 1.9 billion people at risk from mountain water shortages – “The most important water towers are also among the most vulnerable”

By Alejandra Borunda

9 December 2019

(National Geographic) – High in the Himalaya, near the base of the Gangotri glacier, water burbles along a narrow river. Pebbles, carried in the small river’s flow, pling as they carom downstream.

This water will flow thousands of miles, eventually feeding people, farms, and the natural world on the vast, dry Indus plain. Many of the more than 200 million people in the downstream basin rely on water that comes from this stream and others like it.

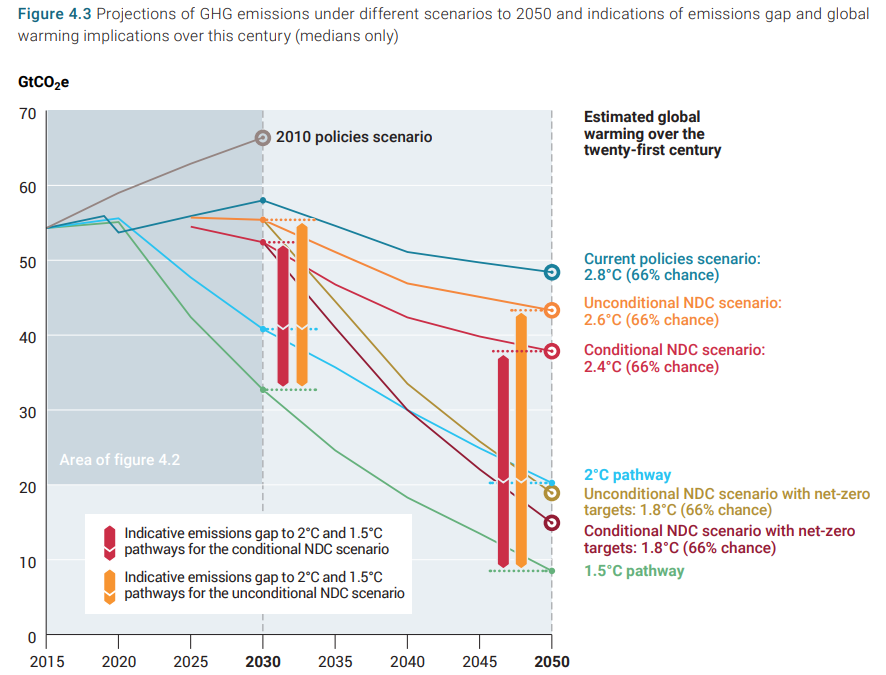

But climate change is hitting those high mountain regions more brutally than the world on average. That change is putting the “water towers” like this one, and the billions of people that depend on them, in ever more precarious positions. New research published Monday in Nature identifies the most important and vulnerable water towers in the world. The research creates a template for world leaders—many of whom gathered at a major annual climate summit last week—to follow as they consider how to prioritize climate adaptation efforts in the face of unprecedented, rapid change.

“We all need water. We’re 90 percent water, we require fresh water,” says Michele Koppes, a climate and glacier scientist at the University of British Columbia and an author of the report. “We have big demands on the water from these water towers, and we have to understand better how they’re changing.”

Why do we care about water towers?

The high mountains cradle more ice and snow in their peaks than exists anywhere else on the planet besides the poles. Over 200,000 glaciers, piles of snow, high-elevation lakes and wetlands: All in all, the high mountains contain about half of all the fresh water humans use.

The snow and icy glaciers that drape the high mountains play a crucial role for over 1.6 billion people—over 20 percent of Earth’s human population today—whether or not they know it. The water you’re drinking may in fact have come from a high-mountain source.

The high-mountain “water towers” of the planet act like giant storage tanks with valves on them. The system more or less works like this: Snow falls, filling the tank, and then it melts out slowly over days, weeks, months, or years—a natural valve that smooths out the boom-bust pattern in outflow that would otherwise occur. [more]

The world’s supply of fresh water is in trouble as mountain ice vanishes

Water Towers of the world ranked on vulnerability

9 December 2019 (Utrecht University) – Scientists from around the world have assessed the planet’s 78 mountain glacier–based water systems and, for the first time, ranked them in order of their importance to adjacent lowland communities, as well as their vulnerability to future environmental and socioeconomic changes. These systems, known as mountain water towers, store and transport water via glaciers, snow packs, lakes and streams, thereby supplying invaluable water resources to 1.9 billion people globally—roughly a quarter of the world’s population.

The research, published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature, provides evidence that global water towers are at risk, in many cases critically, due to the threats of climate change, growing populations, mismanagement of water resources, and other geopolitical factors. Further, the authors conclude that it is essential to develop international, mountain-specific conservation and climate change adaptation policies and strategies to safeguard both ecosystems and people downstream.

The most vulnerable water tower

Globally, the most relied-upon mountain system is the Indus water tower in Asia, according to their research. The Indus water tower—made up of vast areas of the Himalayan mountain range and covering portions of Afghanistan, China, India, and Pakistan—is also one of the most vulnerable. High-ranking water tower systems on other continents are the southern Andes, the Rocky Mountains and the European Alps.

Reliance and vulnerability

To determine the importance of these 78 water towers, researchers analyzed the various factors that determine how reliant downstream communities are upon the supplies of water from these systems. They also assessed each water tower to determine the vulnerability of the water resources, as well as the people and ecosystems that depend on them, based on predictions of future climate and socioeconomic changes.

Of the 78 global water towers identified, the following are the five most relied-upon systems by continent:

- Asia: Indus, Tarim, Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Ganges-Brahmaputra

- Europe: Rhône, Po, Rhine, Black Sea North Coast, Caspian Sea Coast

- North America: Fraser, Columbia and Northwest United States, Pacific and Arctic Coast, Saskatchewan-Nelson, North America-Colorado

- South America: South Chile, South Argentina, Negro, La Puna region, North Chile

Unique research

The study, which was authored by 32 scientists from around the world, was led by Prof. Walter Immerzeel and Dr. Arthur Lutz of Utrecht University, longtime researchers of water and climate change in high mountain Asia.

“What is unique about our study is that we have assessed the water towers’ importance, not only by looking at how much water they store and provide, but also how much mountain water is needed downstream and how vulnerable these systems and communities are to a number of likely changes in the next few decades,” said Immerzeel. Lutz added, “By assessing all glacial water towers on Earth, we identified the key basins that should be on top of regional and global political agendas.”

Perpetual Planet Partnership

This research was supported by National Geographic and Rolex as part of their Perpetual Planet partnership, which aims to shine a light on the challenges facing the Earth’s critical life-support systems, support science and exploration of these systems, and empower leaders around the world to develop solutions to protect the planet.

To learn more, visit atgeo.com/PerpetualPlanet.

Water Towers of the world ranked on vulnerability

Importance and vulnerability of the world’s water towers

ABSTRACT: Mountains are the water towers of the world, supplying a substantial part of both natural and anthropogenic water demands. They are highly sensitive and prone to climate change, yet their importance and vulnerability have not been quantified at the global scale. Here, we present a global Water Tower Index, which ranks all water towers in terms of their water-supplying role and the downstream dependence of ecosystems and society. For each tower, we assess its vulnerability related to water stress, governance, hydropolitical tension and future climatic and socio-economic changes. We conclude that the most important water towers are also among the most vulnerable, and that climatic and socio-economic changes will affect them profoundly. This could negatively impact 1.9 billion people living in (0.3 billion) or directly downstream of (1.6 billion) mountain areas. Immediate action is required to safeguard the future of the world’s most important and vulnerable water towers.