Five reasons the COP25 climate talks failed – “The world is screaming out for climate action but this summit has responded with a whisper”

25 December 2019 (AFP) – The climate summit in Madrid earlier this month did not collapse — but by almost any measure it certainly failed.

Five years after the fragile UN process yielded the world’s first universal climate treaty, COP25 was billed as a mopping-up session to finish guidelines for carbon markets, thus completing the Paris Agreement rulebook.

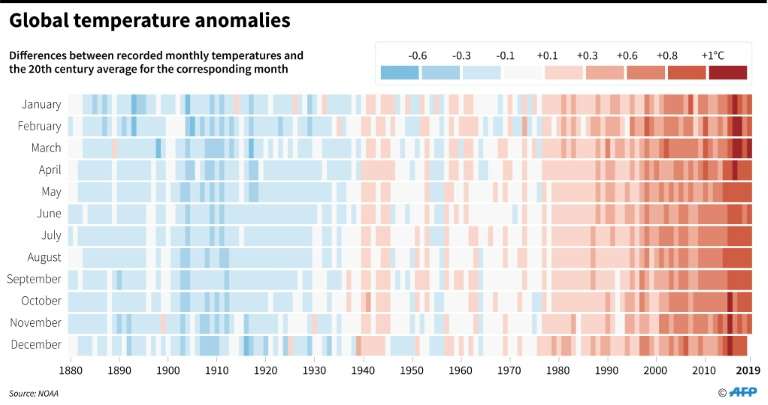

Governments faced with a crescendo of deadly weather, dire alarms from science and weekly strikes by millions of young people were also expected to signal an enhanced willingness to tackle the climate crisis threatening to unravel civilisation as we know it.

The result? A deadlock and a dodge. […]

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres labelled COP25 “disappointing”. Others were more blunt.

“The can-do spirit that birthed the Paris Agreement feels like a distant memory,” said Helen Mountford of Washington-based think tank World Resources Institute (WRI).

“The world is screaming out for climate action but this summit has responded with a whisper,” noted Chema Vera, executive director of Oxfam International.

So what went wrong?

At least five factors contributed to the Madrid meltdown.

Amateur hour

To an unsettling degree, the outcome of a UN climate summit — where 196 nations must sign off on every decision — depends on the savvy and skill of the host country, which acts as a facilitator.

The stars were not aligned for the chaotic Copenhagen summit of 2009 and the Danish prime minister’s less-than-deft manoeuvering did not help. By contrast, the 2015 climate treaty was in no small measure made possible by France’s diplomatic tour-de-force.

This year, Chile’s environment minister Carolina Schmidt wielded the hammer after the conference was moved at the last minute to Madrid due to massive protests on the streets of Santiago.

From Day One, when Schmidt’s mishandling of a request from the African negotiating bloc mushroomed into a diplomatic incident, veteran observers worried that she was not up to the job. […]

Fox in the henhouse

Among the nearly 30,000 diplomats, experts, activists and journalists accredited to attend the summit were hundreds of high-octane fossil fuel lobbyists.

They are collectively the elephant in the room: everyone knows what causes climate change but it is considered impolitic within the UN climate bubble to point fingers.

Even the Paris Agreement turns a blind eye: nowhere in its articles does one find the words oil, natural gas, coal, fossil fuels, or even CO2. […]

“Is there no space free from greenwashing,” asked Mohamed Adow, director of climate think tank Power Shift Africa.

“The UN climate negotiations should be the one place that is free from such fossil fuel interference.”

The Trump effect

On 4 November 2020 — the day after US voters will renew Donald Trump’s mandate or turn him out of office — the United States is set to formally withdraw from the Paris Agreement.

It will be the second time that a Republican White House has plunged a dagger in the heart of a climate treaty nurtured by the Democratic administration that preceded it — the Kyoto Protocol was the previous one.

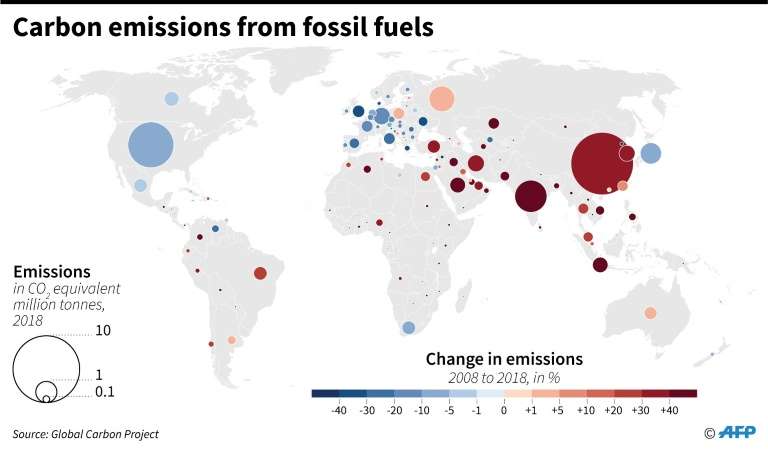

From the moment Trump was elected — on Day Two of COP22 in Marrakesh — advocates of climate action have played down the negative impact of the world’s largest economy and second biggest carbon polluter pulling out of the Paris deal.

But the corrosive “Trump effect” was palpable in Madrid, as was the anger at Washington for twisting arms even as it walked out the door.

“There are one or two parties that seem hell-bent on ensuring any calls for ambition, action, and environmental integrity are rolled back,” said Simon Stiell, Grenada’s environment minister. […]

China at the wheel

When it comes to climate change, Beijing holds the fate of the planet in its hands.

China accounts for 29 percent of global CO2 emissions, more than the next three countries — the US, Russia, India — combined, according to the Global Carbon Project.

Its carbon footprint has tripled in 20 years from 3.2 to 10 billions tonnes in 2018.

The core commitment of China’s voluntary carbon cutting plan, annexed to the Paris treaty, is to stabilise its CO2 output by 2030.

Experts agree that China could hit that mark earlier and more countries are asking Beijing — ever so gingerly — to promise it will.

Granada’s minster Stiell called out half-a-dozen rich and emerging economies — including China and India — for not revising their voluntary plans in line with a world in which warming does not exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Failure to do so, he said, “shows a lack of ambition that also undermines ours”.

“China’s emissions, like the rest of the world’s, need to peak imminently, and then decline rapidly,” for the world to stay under 1.5C or even 2C, according to the Climate Action Tracker, a consortium that analyses climate commitments.

But Beijing has been coy about its intentions. Going into Madrid, it hinted at a revised target ahead of COP26.

But during the Madrid meeting, China dug in its heels and — backed by India — invoked the principle that rich countries must take the lead in addressing climate change, calling out their failure to deliver on promises made. […]

Spitting into the wind

Perhaps the most daunting headwind facing UN climate talks is rising nationalism, populism and economic retrenchment — all at the expense of the multilateralism.

“The stalemate over carbon markets is a symptom of a more general polarisation and lack of cooperation among countries,” said Sebastien Treyer of the IDDRI think tank in Paris.

Street protests, meanwhile, against the rise in cost-of-living in France, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Egypt and more than two dozen other countries in 2019 have given governments already reluctant to invest in a low-carbon future another reason to baulk.

“These cases highlight how sensitive populations are to change in the price of basic commodities like food, energy, and transport,” noted Stephane Hallegatte of the World Bank.

“This is the context in which most countries have committed to stabilise climate change.” [more]