The big business of scavenging in postindustrial America – “The city has survived, in part, by devouring itself”

By Jake Halpern

21 August 2019

(The New York Times Magazine) – Adrian Paisley spends his days hunting for scrap metal: aluminum, brass and (holy of holies) copper. At 42, Paisley, who weighs just 135 pounds, is wiry and muscular. I once saw him move an old refrigerator by himself, hurling it onto his pickup truck as if it were made of Styrofoam. He lives for this kind of thing. Like the time he found an abandoned car, sawed it in half and hoisted it onto his truck using pulleys. “That’s manly,” he recalled. “What dude wouldn’t enjoy cutting a car in half?”

This past summer, I spent several days with Paisley as he drove the streets of Buffalo, N.Y., and its outlying suburbs, trawling the curbs for scrap metal. During our time together, Paisley found a dishwasher, a couple of microwaves, a metal trash can, a refrigerator and an air-conditioner. That last one was a good find because it included copper tubing, which he could sell for a premium, but Paisley’s favorite discovery was a push mower, which he called a “treasure.” He’d been waiting for a mower like this — one that didn’t require gas, which made it eco-friendly and cheap to use. “Come on, man, it don’t get no better than this!” he told me excitedly. Some of what he finds, like the push mower, he keeps; the rest he sells at his local scrapyard.

Paisley eventually drove us into the city’s Broadway-Fillmore district, where we encountered an abandoned 17-story high-rise: Buffalo’s old train terminal. It has been vacant for decades, and beyond its haunted, gray facade, I could discern, in the hazy distance, the overgrown fields where Buffalo’s steel mills once stood.

Paisley survives on the detritus of civilization. Most of his possessions — from his grill, to his sewing machine, to his 20-foot powerboat — have been salvaged from the trash. He also sometimes uses the scrap that he collects to make things. For example, he used scrap to build a furnace and then forge hunting knives. Yes, he hunts — not with a gun but with a bow. Arrows are recyclable. Unlike bullets, there’s no need to buy them.

In general, Paisley doesn’t believe in voting, or government, or Walmart, or banks. That being said, he respects private property. He always asks homeowners before removing trash from their curbs, and he would never take scrap from the train terminal: “I ain’t going to jail for that,” he said. “You crazy?”

I told Paisley that his job, and his very existence, seemed postapocalyptic. “That’s exactly what it’s like, man!” Paisley said. “But instead of me hunting for water, I’m hunting for metal.”

In truth, Paisley is less a survivalist than an entrepreneur, a small player in an enormous industry. The recycling of scrap metal is a $32 billion business in the United States, according to IBISWorld. As virgin materials become increasingly difficult to mine — and demand soars globally for metals — scrap is more important than ever. When he makes a good find, like discovering a length of copper wire, for example, he immediately checks the current prices using an app on his phone called iScrap, which lists the rates for all types of scrap metal. When it comes to copper wire, there’s “bare bright,” “tin coated copper,” “insulated wire copper,” “computer wire” and many others. Depending on the prices, he may opt to cash in right away or hoard it until prices go up. […]

Of all the scrap materials that are recycled, metals are by far the most valuable, which is why so many entrepreneurs like Paisley are hunting for them instead of plastic bottles or old newspapers. Within the scrap world, copper is king, because it’s needed for almost all electrical products — everything from the nation’s power grid to Tesla’s cars.

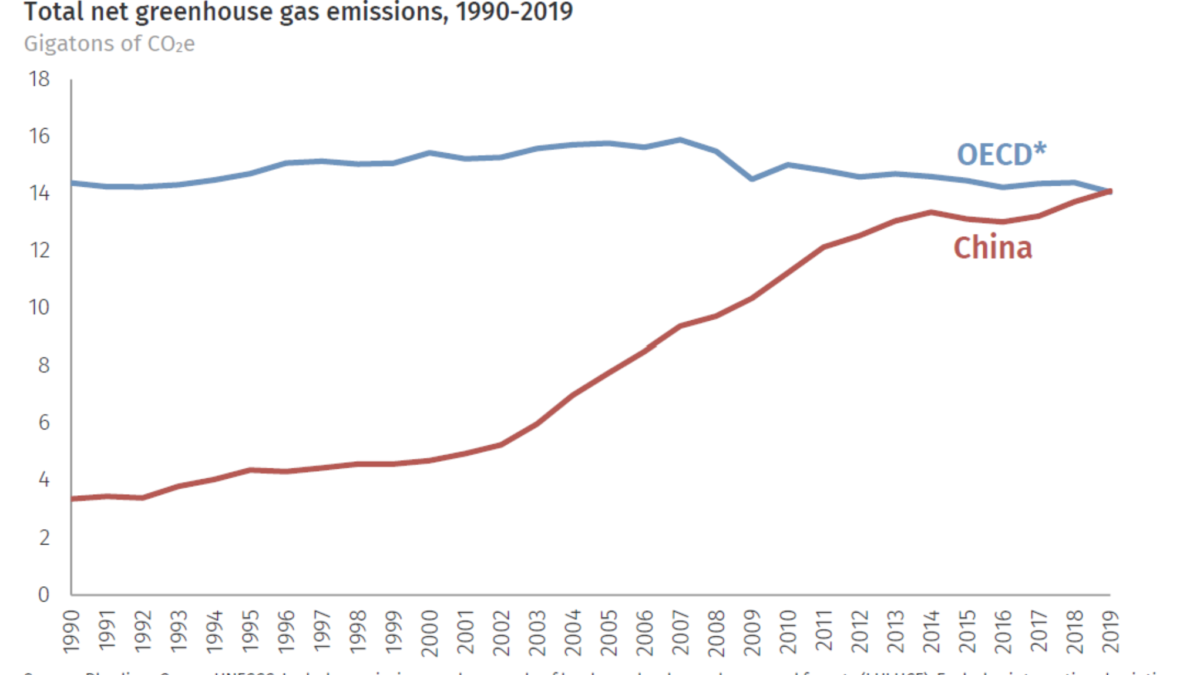

And this copper has become harder and harder to mine. Experts speculate that we will hit peak production levels within the next decade or so. All the while, demand is rising. As China has industrialized, it has devoured virtually all the scrap available on the world market: copper for its power grid, steel for its skyscrapers and nickel for its appliances. For more than a decade, this created an unprecedented boom in the United States’ scrap industry and an enormous incentive to scour every curb, especially in Rust Belt cities like Buffalo. […]

John Hypnarowski later told me that his company, New Enterprise Stone and Lime, also owned some of the land where Bethlehem Steel once existed. The steel mills had been scrapped long ago, but there were still nuggets to be had — or “buttons” to be precise. Buttons are essentially giant metal boulders that weigh as much as 20 tons. When the mills were still operating, iron ore was melted and poured into great big ladles, at which point the less desirable slag would form at the bottom. This slag was then dumped onto Lake Erie’s shoreline, where it hardened and formed buttons. Together, Hypnarowski and Levin worked to salvage these buttons from the lakeside. They had, it seemed, thought of every conceivable way to mine big scrap. Over time, scrappers have remade Buffalo’s landscape. The city has survived, in part, by devouring itself. [more]