A chilling scientific paper helped upend U.S. and U.K. coronavirus strategies – “Even if all patients were able to be treated, there would still be in the order of 250,000 deaths in Great Britain, and 1.2 million in the U.S.”

By William Booth

17 March 2020

LONDON (The Washington Post) – Immediately after Boris Johnson completed his Monday evening news conference, which saw a somber prime minister encourage his fellow citizens to avoid “all nonessential contact with others,” his aides hustled reporters into a second, off-camera briefing.

That session presented jaw-dropping numbers from some of Britain’s top modelers of infectious disease, who predicted the deadly course of coronavirus could quickly kill hundreds of thousands in both the United Kingdom and the United States, as surges of sick and dying patients overwhelmed hospitals and critical care units.

The new forecasts, by Neil Ferguson and his colleagues at the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, were quickly embraced by Johnson’s government to design new and more-extreme measures to suppress the spread of the virus.

The report is also influencing planning by the Trump administration. Deborah Birx, who serves as the coordinator of the White House coronavirus task force, cited the British analysis at a news conference Monday, saying her task force was especially focused on the report’s conclusion that an entire household should self-quarantine for 14 days if one of its members is stricken by the virus.

We might be living in a very different world for a year or more.

Neil Ferguson, professor of mathematical biology, Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

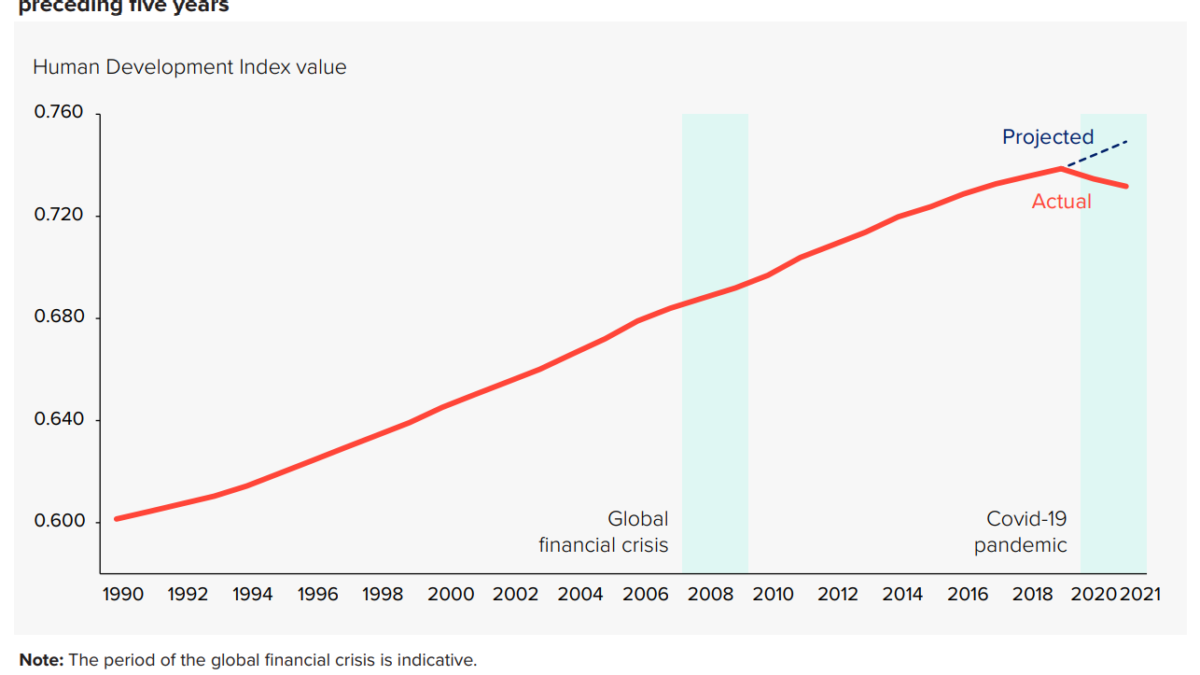

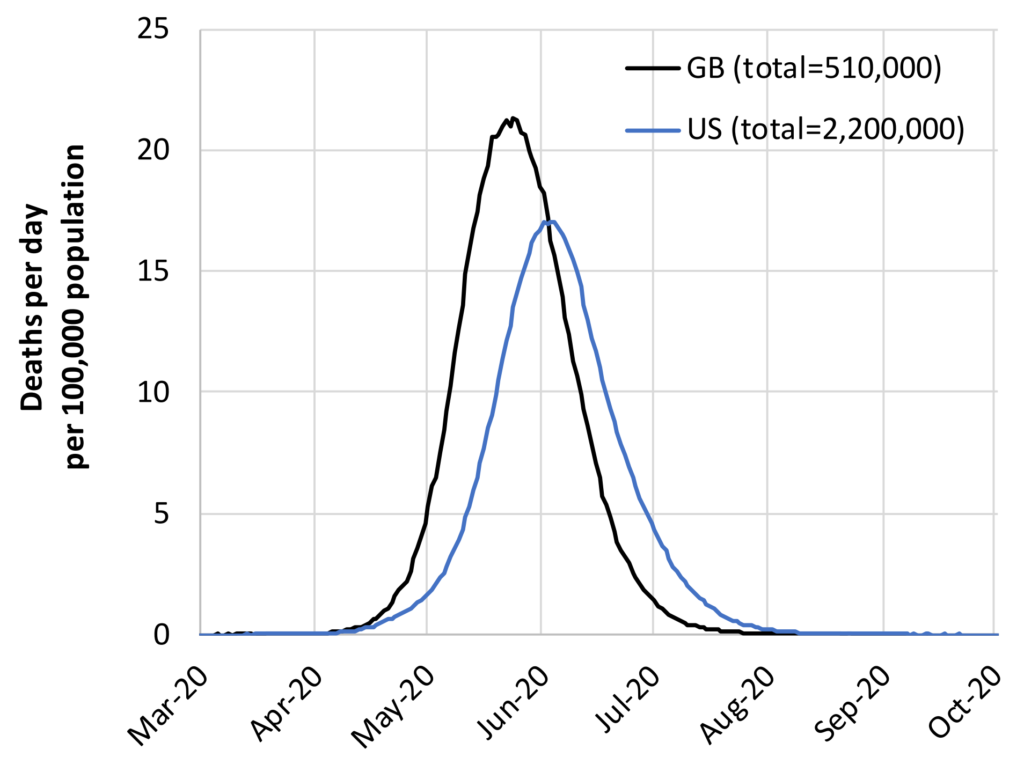

The Imperial College group reported that if nothing was done by governments and individuals and the pandemic remained uncontrolled, then 510,000 would die in Britain and 2.2 million in the United States over the course of the outbreak.

These kinds of numbers are deeply concerning for countries with top-drawer health-care systems. They are terrifying for less-developed countries, global health experts say.

If Britain and the United States pursued much more ambitious measures to mitigate the spread of coronavirus, to slow but not necessarily stop epidemic over the coming few months, they could reduce mortality by half, to 260,000 people in the United Kingdom and 1.1 million in the United States. […]

“We might be living in a very different world for a year or more,” Ferguson told reporters. [more]

A chilling scientific paper helped upend U.S. and U.K. coronavirus strategies

COVID-19: Imperial researchers model likely impact of public health measures

By Ryan O’Hare

17 March 2020

(Imperial College) — Researchers from Imperial have analysed the likely impact of multiple public health measures on slowing and suppressing the spread of coronavirus.

The latest analysis comes from a team modelling the spread and impact COVID-19 and whose data are informing current UK government policy on the pandemic.

The findings are published in the 9th report from the WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling within the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, J-IDEA, Imperial College London.

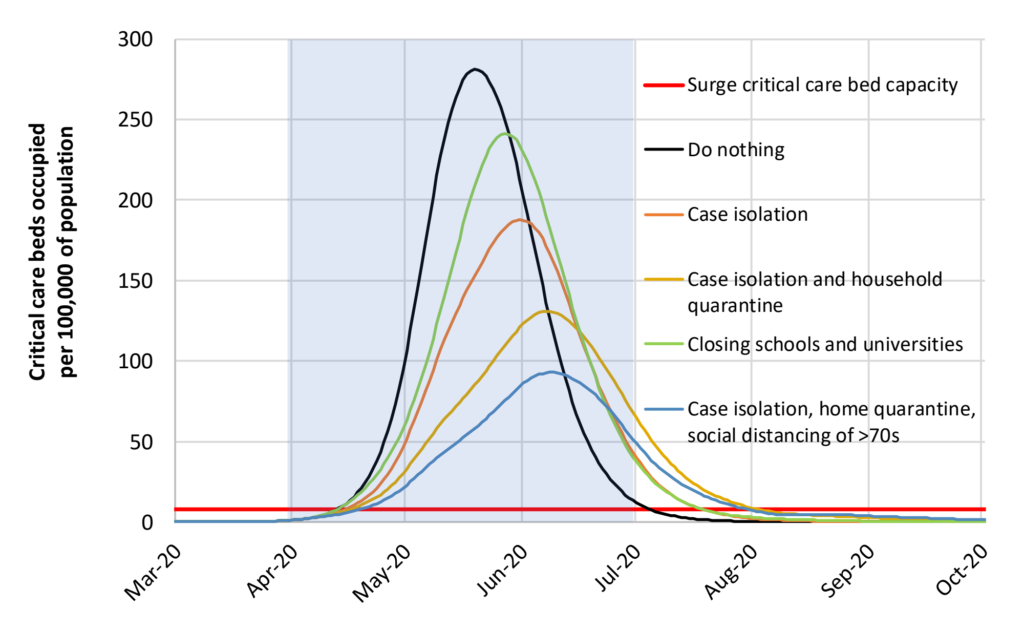

Perhaps our most significant conclusion is that mitigation is unlikely to be feasible without emergency surge capacity limits of the U.K. and U.S. healthcare systems being exceeded many times over. In the most effective mitigation strategy examined, which leads to a single, relatively short epidemic (case isolation, household quarantine and social distancing of the elderly), the surge limits for both general ward and ICU beds would be exceeded by at least 8-fold under the more optimistic scenario for critical care requirements that we examined. In addition, even if all patients were able to be treated, we predict there would still be in the order of 250,000 deaths in Great Britain, and 1.1-1.2 million in the U.S.

Ferguson, et al., 2020 / Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand”, p. 16.

Professor Neil Ferguson, head of the MRC GIDA team and director of the Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics (J-IDEA), said: “The world is facing the most serious public health crisis in generations. Here we provide concrete estimates of the scale of the threat countries now face.

“We use the latest estimates of severity to show that policy strategies which aim to mitigate the epidemic might halve deaths and reduce peak healthcare demand by two-thirds, but that this will not be enough to prevent health systems being overwhelmed. More intensive, and socially disruptive interventions will therefore be required to suppress transmission to low levels. It is likely such measures – most notably, large scale social distancing – will need to be in place for many months, perhaps until a vaccine becomes available.”

Combining multiple measures

In the current absence of vaccines and effective drug treatments, there are several public health measures countries can take to help slow the spread of the COVID-19. The team focused on the impact of five such measures, alone and in combination:

- Home isolation of cases – whereby those with symptoms of the disease (cough and/or fever) remain at home for 7 days following the onset of symptoms

- Home quarantine – whereby all household members of those with symptoms of the disease remain at home for 14 days following the onset of symptoms

- Social distancing – a broad policy that aims to reduce overall contacts that people make outside the household, school or workplace by three-quarters.

- Social distancing of those over 70 years – as for social distancing but just for those over 70 years of age who are at highest risk of severe disease

- Closure of schools and universities

Modelling available data, the team found that depending on the intensity of the interventions, combinations would result in one of two scenarios.

In the first scenario, they show that interventions could slow down the spread of the infection but would not completely interrupt its spread. They found this would reduce the demand on the healthcare system while protecting those most at risk of severe disease. Such epidemics are predicted to peak over a three to four-month period during the spring/summer.

In the second scenario, more intensive interventions could interrupt transmission and reduce case numbers to low levels. However, once these interventions are relaxed, case numbers are predicted to rise. This gives rise to lower case numbers, but the risk of a later epidemic in the winter months unless the interventions can be sustained.

Slowing and suppressing the outbreak

The report details that for the first scenario (slowing the spread), the optimal policy would combine home isolation of cases, home quarantine and social distancing of those over 70 years. This could reduce the peak healthcare demand by two-thirds and reduce deaths by half. However, the resulting epidemic would still likely result in an estimated 260,000 deaths and therefore overwhelm the health system (most notably intensive care units).

In the second scenario (supressing the outbreak), the researchers show this is likely to require a combination of social distancing of the entire population, home isolation of cases and household quarantine of their family members (and possible school and university closure). The researchers explain that by closely monitoring disease trends it may be possible for these measures to be relaxed temporarily as things progress, but they will need to be rapidly re-introduced if/when case numbers rise. They add that the situation in China and South Korea in the coming weeks will help to inform this strategy further.

Professor Azra Ghani, Chair in Infectious Disease Epidemiology from the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, said: “The current situation with the COVID-19 pandemic is evolving rapidly; governments and societies therefore need to be flexible in responding the challenges it poses. Our results indicate that widescale social distancing measures, that are likely to have a major impact on our day-to-day lives, are now necessary to reduce further spread and prevent our health system being overwhelmed. Close monitoring will be required in the coming weeks and months to ensure that we minimise the health impact of this disease.”

For an uncontrolled epidemic, we predict critical care bed capacity would be exceeded as early as the second week in April, with an eventual peak in ICU or critical care bed demand that is over 30 times greater than the maximum supply in both countries.

Ferguson, et al., 2020 / Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand”, p. 7.

Professor Christl Donnelly, Professor of Statistical Epidemiology within J-IDEA, said: “The challenges we collectively face are daunting. However, our work indicates if a combination of measures are implemented, then transmission can be substantially reduced. These measures will be disruptive but uncertainties will reduce over time, and while we await effective vaccines and drugs, these public health measures can reduce demands on our healthcare systems.”

Professor Steven Riley, Professor of Infectious Disease Dynamics within J-IDEA, said: “We have to accept that COVID-19 is a severe infection and it is currently able to spread in countries such as the US and the UK. In this report, we show that the most stringent traditional interventions are required in the short term to halt its spread. Once they are in place, it becomes a common priority for us all to find the best possible ways to improve on those interventions”

COVID-19: Imperial researchers model likely impact of public health measures