Western honeybee colonies at risk of collapse, WSU study finds – “They’re really the glue in our ecosystems. And you never notice the glue — until it stops working.”

By Conrad Swanson

1 April 2024

(The Seattle Times) – One of nature’s most important keystone species is working itself to death.

Colonies of honeybees — crucial pollinators for a wide variety of plants and cash crops — are at risk of collapse because of climate change, a recent study by scientists at Washington State University and the U.S. Department of Agriculture found.

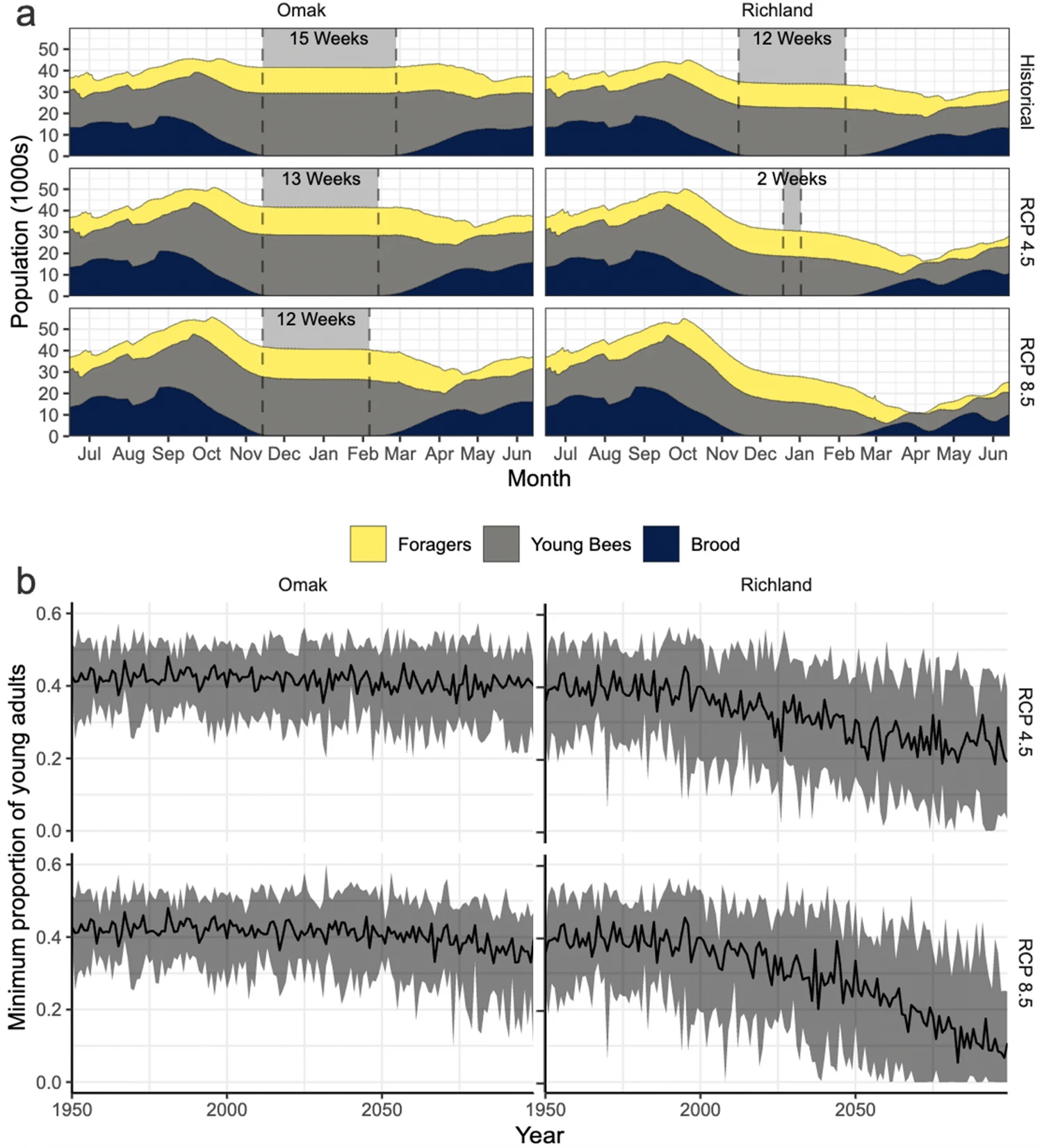

Long and warmer fall months across the Pacific Northwest encourage bees to emerge from their colonies when they should be resting, said Gloria DeGrandi-Hoffman, a research leader at the USDA’s Carl Hayden Bee Research Center in Arizona.

“When it’s warm out, they fly and when they fly they’re physiologically aging,” said DeGrandi-Hoffman, who is also one of the study’s authors. “It’s very taxing to fly.”

Come springtime, bees that should be emerging young and rested are instead elderly and infirm, she said. They’re too old to care for younger bee generations, which in turn cannot care for the generations after them.

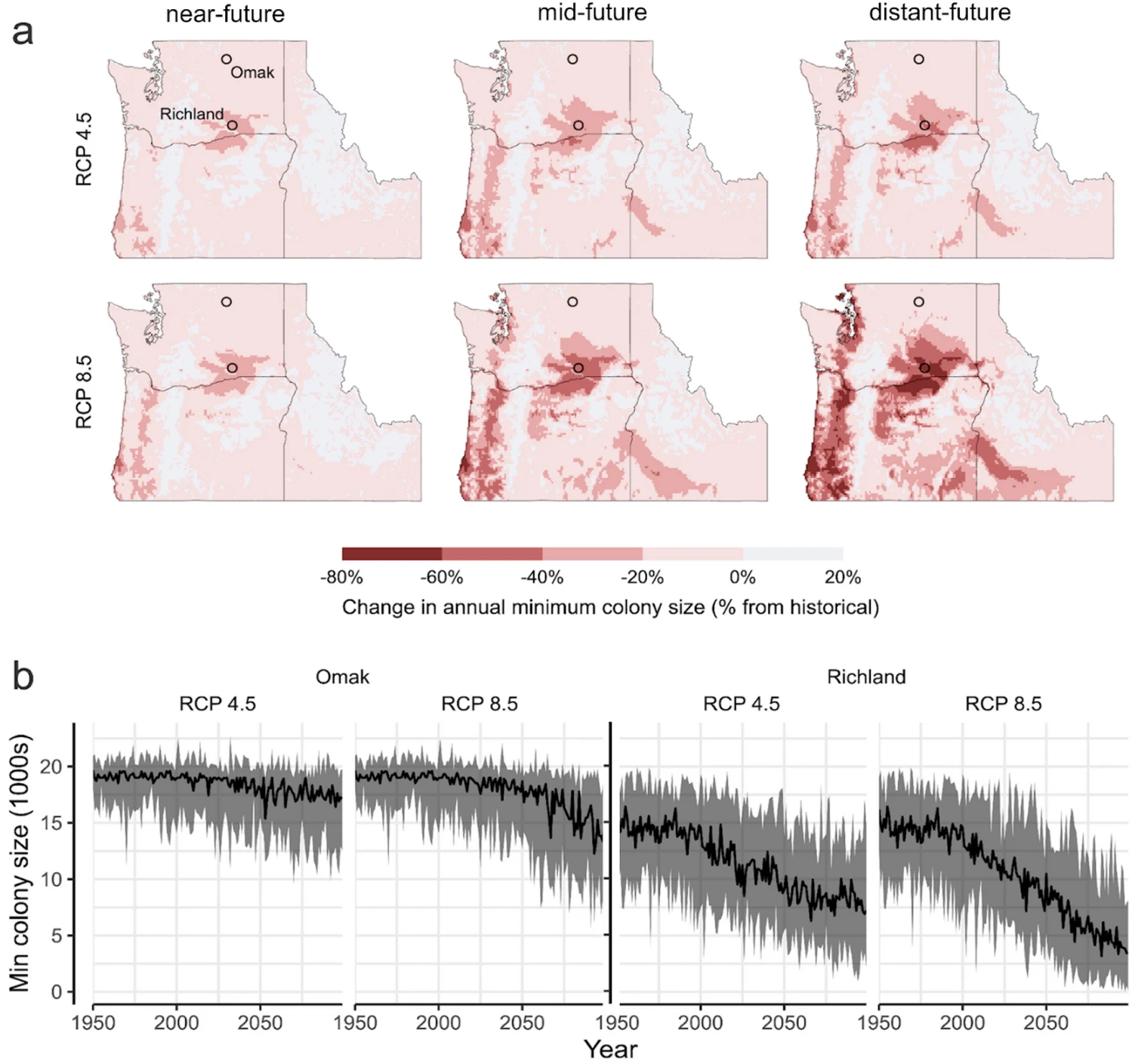

When the colonies sink below a certain threshold (around 5,000 bees), multiple things start to go wrong and the population spirals, said Brandon Hopkins, another author and manager of WSU’s apiary program and laboratory. The bees will no longer be able to keep warm, nursing bees can’t feed the developing brood and there won’t be enough bees to forage for food.

“Everything falls apart,” Hopkins said. “The whole system crashes.”

All because of a few degrees’ increase in temperature.

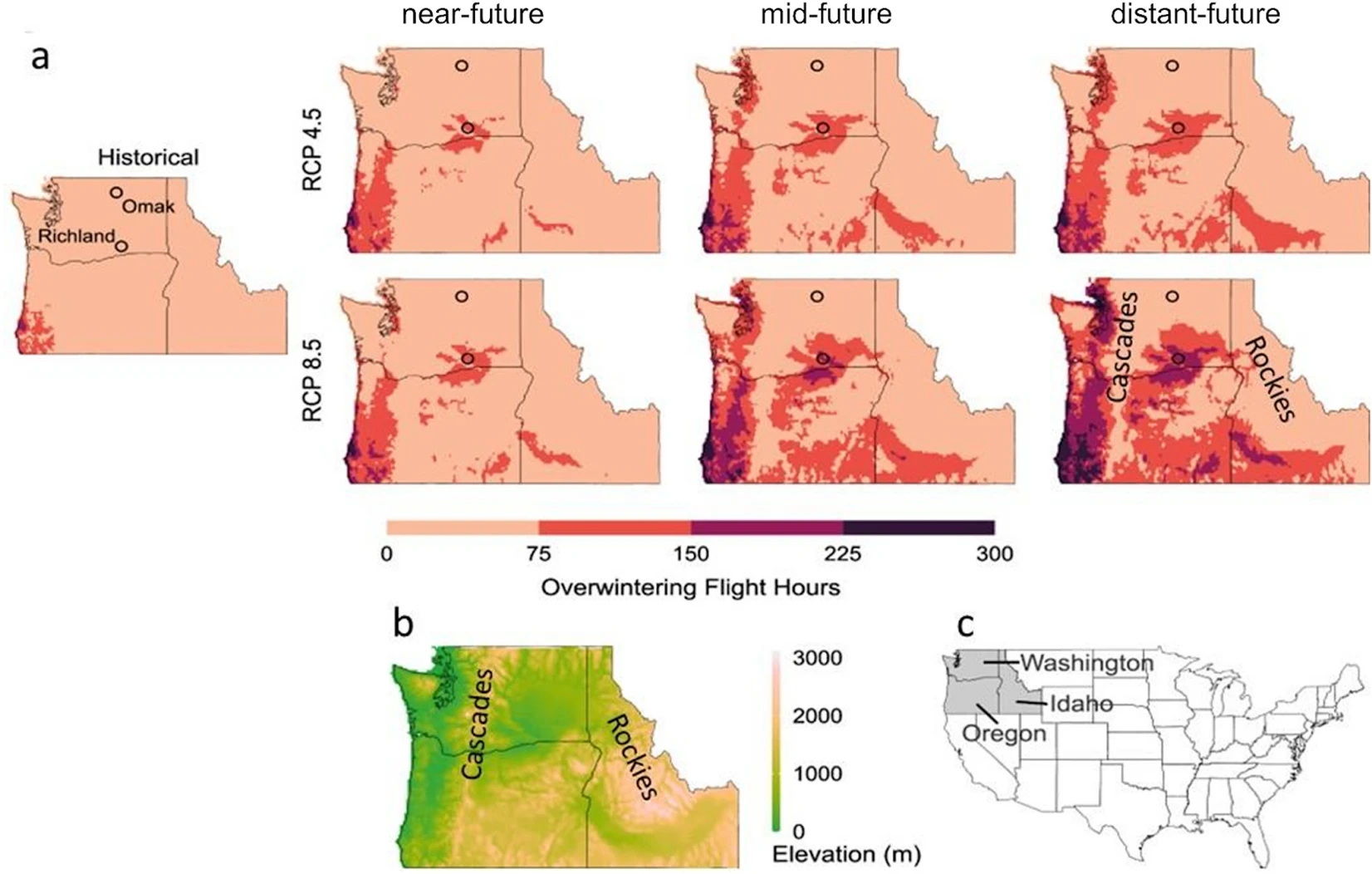

The study modeled many different climate scenarios for the decades ahead, said Kirti Rajagopalan, another author, and an assistant professor in WSU’s Department of Biological Systems Engineering. How severe the warming trend continues for the Pacific Northwest depends on whether humans curtail greenhouse gas emissions and, if so, by how much.

Warmer fall and winter months don’t happen every year, and the Earth will continue to see its natural variability, but climate change pushes each end of the spectrum to greater extremes than before.

Not only did global temperatures mark the hottest year on record in 2023 but regional temperatures consistently hit record highs as well.

By 2050 those warm swings for fall and winter months could push between 4 or 5 degrees above normal, Rajagopalan said.

“Two degrees might not make a big difference at the beach,” Hopkins said. “But it can be the difference between bees flying and not flying.”

The difference between a sustainable bee colony and collapse.

Some years between 40% and 60% of bee colonies collapse across the country, DeGrandi-Hoffman said. The consequences will become more and more apparent.

Not only can the study’s findings apply to bees outside of the Pacific Northwest, but other pollinators are suffering as well, DeGrandi-Hoffman said.

“They’re really the glue in our ecosystems,” she said. “And you never notice the glue — until it stops working.”

With bees specifically, that glue (pollination) produces about a third of our diets as humans, Hopkins said.

“Generally the most nutritious and delicious foods that we have,” he said. “Fruits and vegetables and many of the nuts are produced by bees.” [more]

Western honeybee colonies at risk of collapse, WSU study finds

Warmer autumns and winters could reduce honey bee overwintering survival with potential risks for pollination services

ABSTRACT: Honey bees and other pollinators are critical for food production and nutritional security but face multiple survival challenges. The effect of climate change on honey bee colony losses is only recently being explored. While correlations between higher winter temperatures and greater colony losses have been noted, the impacts of warmer autumn and winter temperatures on colony population dynamics and age structure as an underlying cause of reduced colony survival have not been examined. Focusing on the Pacific Northwest US, our objectives were to (a) quantify the effect of warmer autumns and winters on honey bee foraging activity, the age structure of the overwintering cluster, and spring colony losses, and (b) evaluate indoor cold storage as a management strategy to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change. We perform simulations using the VARROAPOP population dynamics model driven by future climate projections to address these objectives. Results indicate that expanding geographic areas will have warmer autumns and winters extending honey bee flight times. Our simulations support the hypothesis that late-season flight alters the overwintering colony age structure, skews the population towards older bees, and leads to greater risks of colony failure in the spring. Management intervention by moving colonies to cold storage facilities for overwintering has the potential to reduce honey bee colony losses. However, critical gaps remain in how to optimize winter management strategies to improve the survival of overwintering colonies in different locations and conditions. It is imperative that we bridge the gaps to sustain honey bees and the beekeeping industry and ensure food and nutritional security.