Petrostates planning huge expansion of fossil fuels, says UN report – “These plans throw humanity’s future into question. Governments must stop saying one thing and doing another.”

By Damian Carrington

8 November 2023

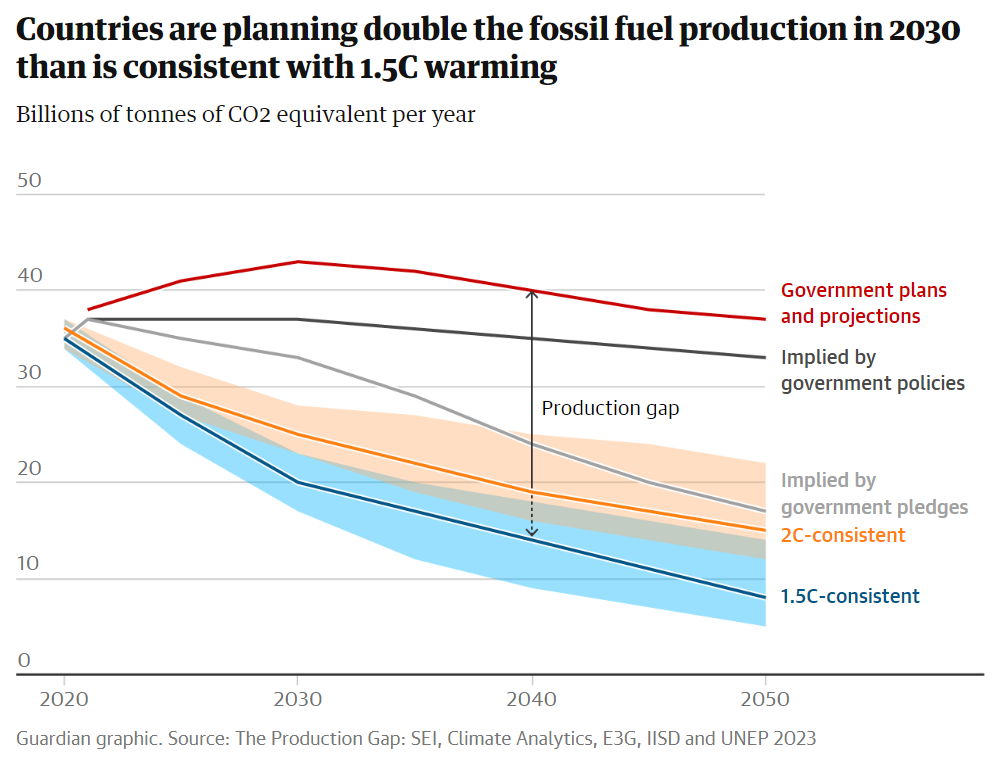

(The Guardian) – The world’s fossil fuel producers are planning expansions that would blow the planet’s carbon budget twice over, a UN report has found. Experts called the plans “insanity” which “throw humanity’s future into question”.

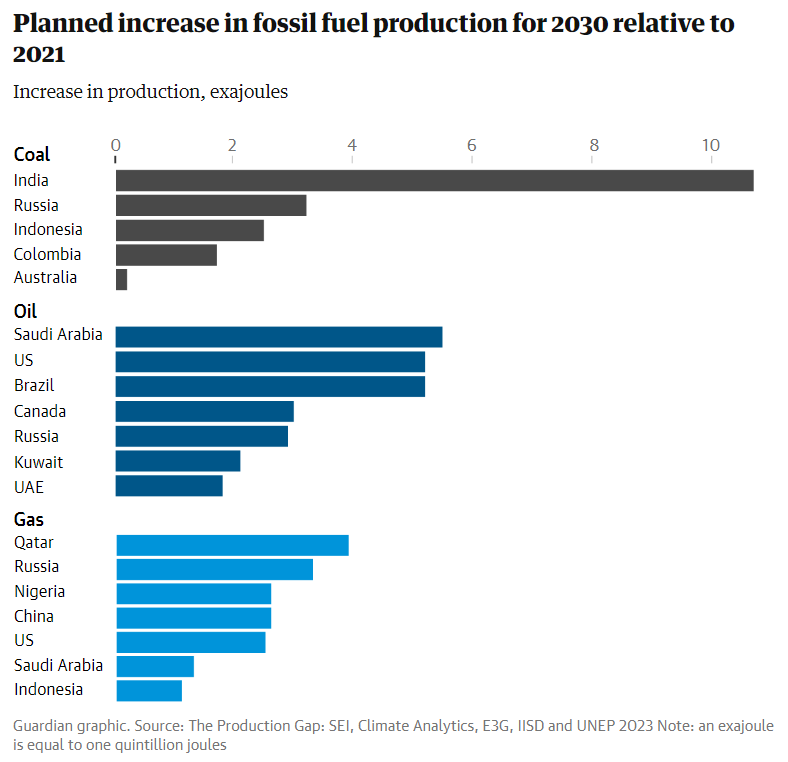

The energy plans of the petrostates contradicted their climate policies and pledges, the report said. The plans would lead to 460% more coal production, 83% more gas, and 29% more oil in 2030 than it was possible to burn if global temperature rise was to be kept to the internationally agreed 1.5C. The plans would also produce 69% more fossil fuels than is compatible with the riskier 2C target.

The countries responsible for the largest carbon emissions from planned fossil fuel production are India (coal), Saudi Arabia (oil) and Russia (coal, oil and gas). The US and Canada are also planning to be major oil producers, as is the United Arab Emirates. The UAE is hosting the crucial UN climate summit Cop28, which starts on 30 November.

The report sets out starkly the fundamental conflict driving the climate crisis: fossil fuel burning must rapidly be cut down to zero, yet petrostates and companies intend to keep on making trillions of dollars a year by increasing production.

“The addiction to fossil fuels still has its claws deep in many nations,” said Inger Andersen, the executive director of the UN environment programme. “These plans throw humanity’s future into question. Governments must stop saying one thing and doing another.”

Neil Grant, an analyst at the Climate Analytics thinktank and an author of the report, said: “Despite their climate promises, governments’ plan on ploughing yet more money into a dirty, dying industry, while opportunities abound in a flourishing clean energy sector. On top of economic insanity, it is a climate disaster of our own making.”

The report profiles 20 fossil fuel-producing nations, which were the combined source of 84% of CO2 emissions in 2021. Of those, 17 had pledged to achieve net zero emissions, said Michael Lazarus at the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), a lead author of the report.

“[The problem is] the desire for each country to maximise their own production,” he said. There needed to be an internationally coordinated and equitable global phase-out of fossil fuels, Lazarus said.

A long series of scientific studies has concluded that any new oil and gas fields are incompatible with staying below the 1.5C global heating limit agreed in Paris, including a 2021 analysis by the International Energy Agency. The Guardian revealed in 2022 that the world’s biggest fossil fuel businesses were planning scores of “carbon bomb” oil and gas projects.

The new report analysed the expansion plans of the big fossil fuel producers based on publicly available data. It found the gap between planned production and the amount consistent with keeping to 1.5C of global heating was as large now as when the analysis was first done in 2019. The gap in 2030 is estimated at 20bn tonnes of CO2, about half of today’s annual global emissions.

After Saudi Arabia, the US, Brazil, and Canada have the next biggest oil expansion plans and the Cop28 host UAE is seventh on the list. Qatar has the biggest gas expansion plans and Nigeria is third, after Russia. India’s coal expansion plans are enormous: three times that of second-placed Russia, with Indonesia in third and Australia in fifth.

Overall, only four countries have plans under which overall emissions from the fossil fuels they produce would fall: the UK, China, Norway and Germany. [more]

‘Insanity’: petrostates planning huge expansion of fossil fuels, says UN report

Nations must go further than current Paris pledges or face global warming of 2.5-2.9°C

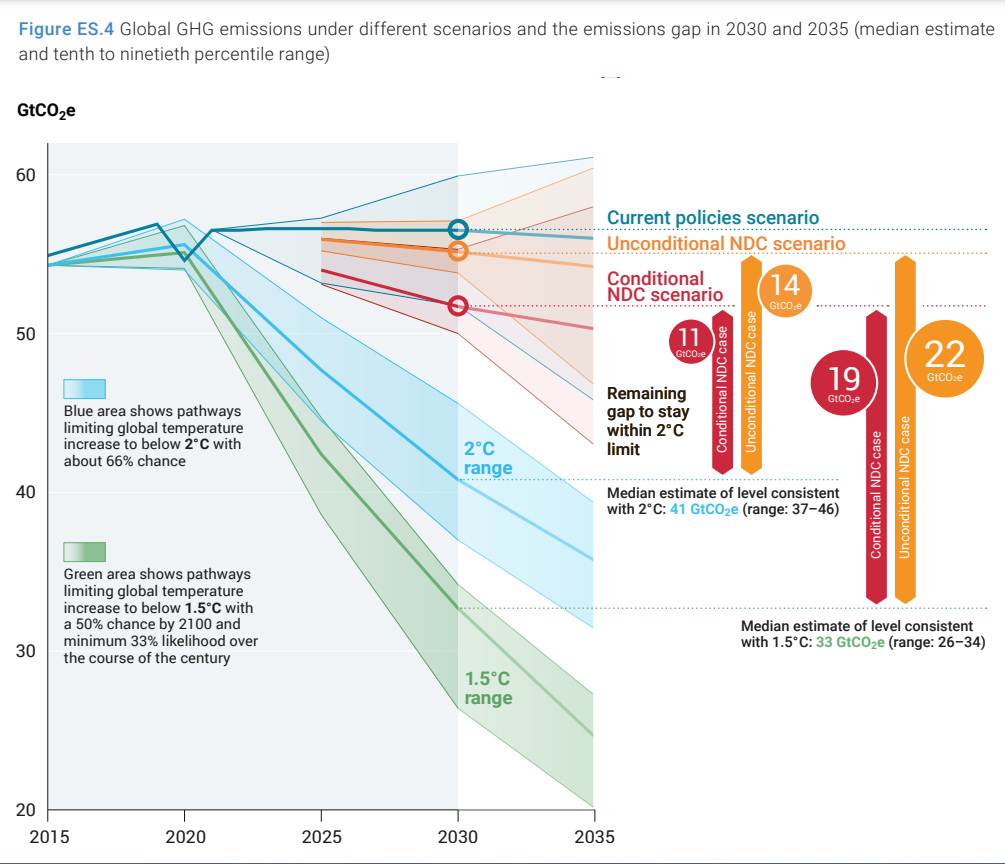

Nairobi, 20 November 2023 (UNEP) – As global temperatures and greenhouse gas emissions break records, the latest Emissions Gap Report from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) finds that current pledges under the Paris Agreement put the world on track for a 2.5-2.9°C temperature rise above pre-industrial levels this century, pointing to the urgent need for increased climate action.

Released ahead of the 2023 climate summit in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, the Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record – Temperatures hit new highs, yet world fails to cut emissions (again), finds that global low-carbon transformations are needed to deliver cuts to predicted 2030 greenhouse gas emissions of 28 per cent for a 2°C pathway and 42 per cent for a 1.5°C pathway.

“We know it is still possible to make the 1.5 degree limit a reality. It requires tearing out the poisoned root of the climate crisis: fossil fuels. And it demands a just, equitable renewables transition,” said Antònio Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Maintaining the possibility of achieving the Paris Agreement temperature goals hinges on significantly strengthening mitigation this decade to narrow the emissions gap. This will facilitate more ambitious targets for 2035 in the next round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and increase the chances of meeting net-zero pledges, which now cover around 80 per cent of global emissions.

“There is no person or economy left on the planet untouched by climate change, so we need to stop setting unwanted records on greenhouse gas emissions, global temperature highs and extreme weather,” said Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP. “We must instead lift the needle out of the same old groove of insufficient ambition and not enough action, and start setting other records: on cutting emissions, on green and just transitions and on climate finance.”

Broken records

Until the beginning of October this year, 86 days were recorded with temperatures over 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. September was the hottest recorded month ever, with global average temperatures 1.8°C above pre-industrial levels.

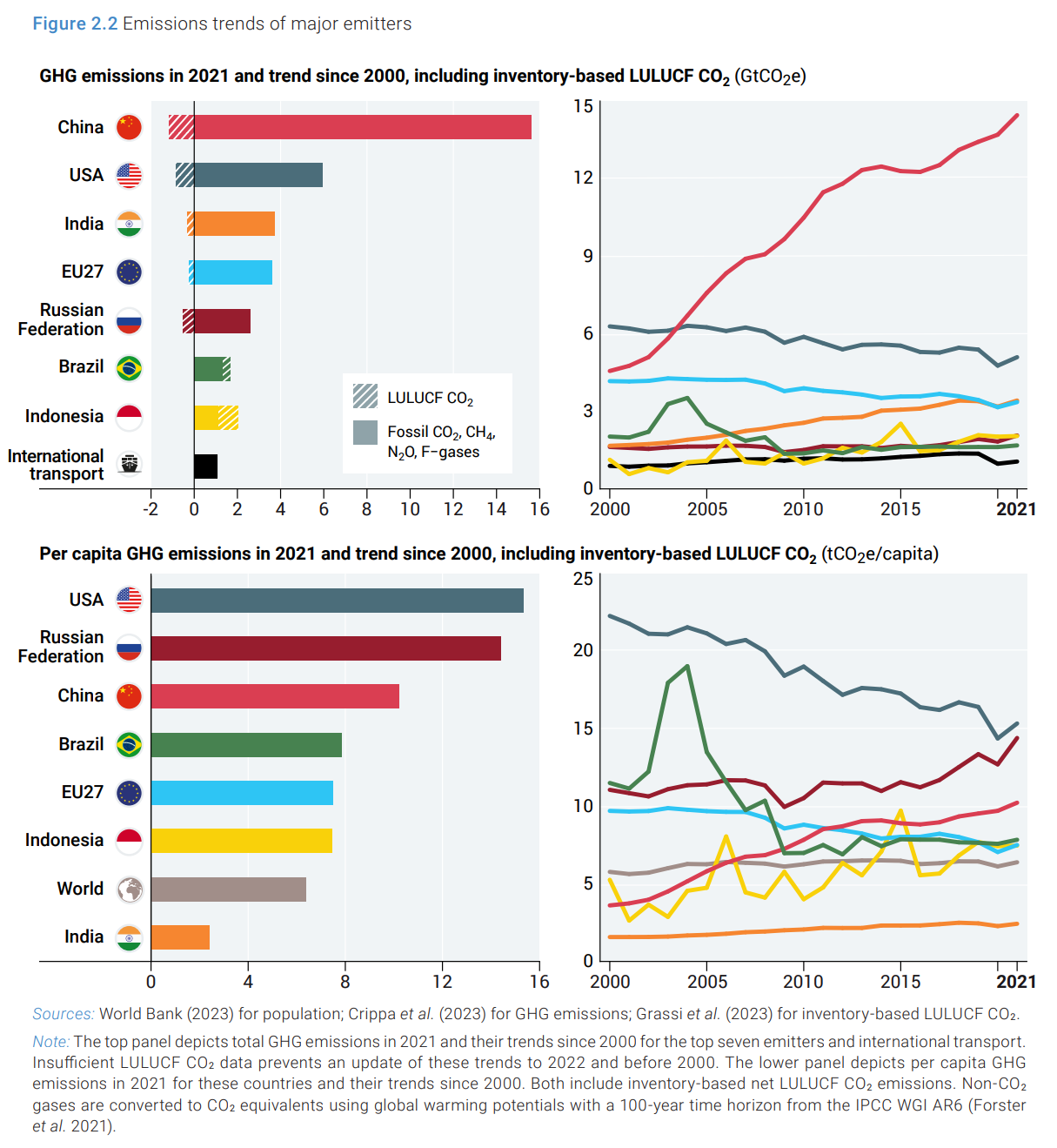

The report finds that global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions increased by 1.2 per cent from 2021 to 2022 to reach a new record of 57.4 Gigatonnes of Carbon Dioxide Equivalent (GtCO2e). GHG emissions across the G20 increased by 1.2 per cent in 2022. Emissions trends reflect global patterns of inequality. Because of these worrying trends and insufficient mitigation efforts, the world is on track for a temperature rise far beyond the agreed climate goals during this century.

If mitigation efforts implied by current policies are continued at today’s levels, global warming will only be limited to 3°C above pre-industrial levels in this century. Fully implementing efforts implied by unconditional Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) would put the world on track for limiting temperature rise to 2.9°C. Conditional NDCs fully implemented would lead to temperatures not exceeding 2.5°C above pre-industrial levels. All of these are with a 66 per cent chance.

These temperature projections are slightly higher than in the 2022 Emissions Gap Report, as the 2023 report includes a larger number of models in the estimation of global warming.

Current unconditional NDCs imply that additional emissions cuts of 14 GtCO2e are needed in 2030 over predicted levels for 2°C. Cuts of 22 GtCO2e are needed for 1.5°C. The implementation of conditional NDCs reduces both these estimates by 3 GtCO2e.

In percentage terms, the world needs to cut 2030 emissions by 28 per cent to get on track to achieve the 2°C goal of the Paris Agreement, with a 66 per cent chance, and 42 per cent for the 1.5°C goal.

If all conditional NDCs and long-term net-zero pledges were met, limiting the temperature rise to 2°C would be possible. However, net-zero pledges are not currently considered credible: none of the G20 countries are reducing emissions at a pace consistent with their net-zero targets. Even in the most optimistic scenario, the likelihood of limiting warming to 1.5°C is only 14 per cent.

Some progress, but not enough

Policy progress since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015 has reduced the implementation gap, defined as the difference between projected emissions under current policies and full NDC implementation. GHG emissions in 2030 based on policies in place were projected to increase by 16 per cent at the time of the adoption of the Paris Agreement. Today, the projected increase is 3 per cent.

As of 25 September, nine countries had submitted new or updated NDCs since COP27 in 2022, bringing the total number of updated NDCs to 149. If all new and updated unconditional NDCs are fully implemented, they would likely reduce GHG emissions by about 5.0 GtCO2e, about 9 per cent of 2022 emissions, annually by 2030, compared with the initial NDCs.

However, unless emission levels in 2030 are brought down further, it will become impossible to establish least-cost pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C with no or low overshoot during this century. Significantly ramping up implementation in this decade is the only way to avoid significant overshoot of 1.5°C.

Low-carbon development transformations

The report calls for all nations to deliver economy-wide, low-carbon development transformations, with a focus on the energy transition. The coal, oil and gas extracted over the lifetime of producing and planned mines and fields would emit over 3.5 times the carbon budget available to limit warming to 1.5°C, and almost the entire budget available for 2°C.

Countries with greater capacity and responsibility for emissions – particularly high-income and high-emitting countries among the G20 – will need to take more ambitious and rapid action and provide financial and technical support to developing nations. As low- and middle-income countries already account for more than two thirds of global GHG emissions, meeting development needs with low-emissions growth is a priority in such nations – such as addressing energy demand patterns and prioritizing clean energy supply chains.

The low-carbon development transition poses economic and institutional challenges for low- and middle-income countries, but also provides significant opportunities. Transitions in such countries can help to provide universal access to energy, lift millions out of poverty and expand strategic industries. The associated energy growth can be met efficiently and equitably with low-carbon energy as renewables get cheaper, ensuring green jobs and cleaner air.

To achieve this, international financial assistance will have to be significantly scaled up, with new public and private sources of capital restructured through financing mechanisms – including debt financing, long-term concessional finance, guarantees and catalytic finance – that lower the costs of capital.

COP28 and the Global Stocktake

The first Global Stocktake (GST), concluding at COP28, will inform the next round of NDCs that countries should submit in 2025, with targets for 2035. Global ambition in the next round of NDCs must bring GHG emissions in 2035 to levels consistent with 2°C and 1.5°C pathways, while compensating for excess emissions until levels consistent with these pathways are achieved.

The preparation of the next round of NDCs offers the opportunity for low- and middle-income countries to develop national roadmaps with ambitious development and climate policies, and targets for which finance and technology needs are clearly specified. COP28 should ensure that international support is provided for the development of such roadmaps.

Carbon dioxide removal

The report finds that delaying GHG emissions reductions will increase future reliance on carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide removal is already being deployed, mainly through afforestation, reforestation and forest management. Current direct removals through land-based methods are estimated at 2 GtCO2e annually. However, least-cost pathways assume considerable increases in both conventional and novel carbon dioxide removal – such as direct air carbon capture and storage.

Achieving higher levels of carbon dioxide removal remains uncertain and associated with risks: around land competition, protection of tenure and rights and other factors. Upscaling of novel carbon dioxide removal methods are associated with different types of risks, including that the technical, economic and political requirements for large-scale deployment may not materialize in time.

Contact

- News and Media Unit, UN Environment Programme

Nations must go further than current Paris pledges or face global warming of 2.5-2.9°C