“All I see are ghosts”: fear and fury as the last spotted owl in Canada fights for survival

By Leyland Cecco

26 May 2023

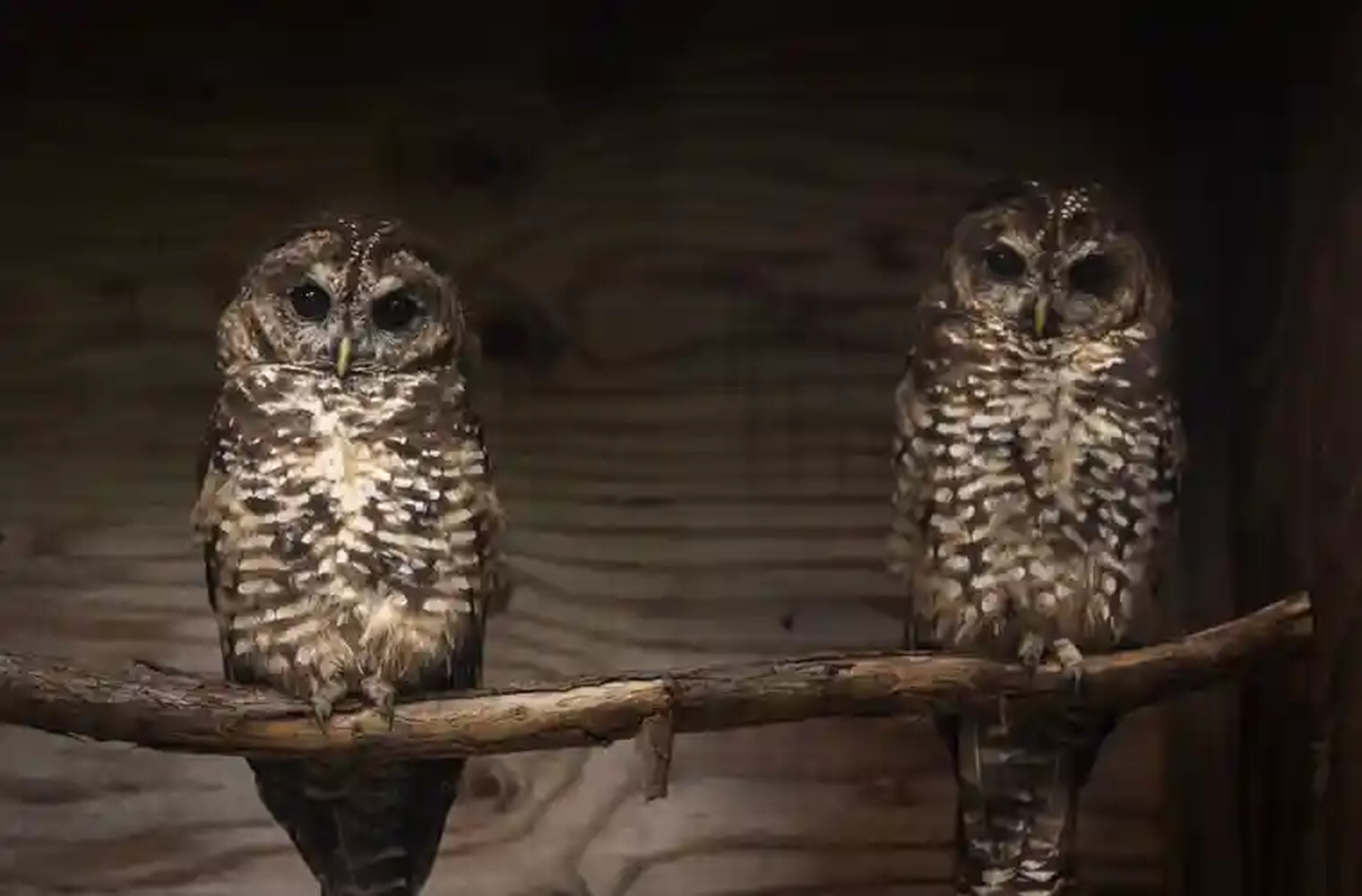

Spô’zêm First Nation, Canada (The Guardian) – On a rainy spring morning, huddled under the shelter of an ancient cedar, Jared Hobbs hoots, whoops and squawks. In years past, he could lure curious owls by drawing on his extensive repertoire. Among them are the whoo whoo whoo whooo territorial calls, alarm barks and a simple “helicopter” breeding call that coo coo coo coos into the air.

The calls bounce through the thick stand of trees and dissolve into the vast British Columbia rainforest.

Hobbs doesn’t wait for a response. Only one spotted owl remains in the Canadian wild, less than two kilometres from where he stands. Her precise location in the misty forest is a closely guarded secret and her lonely presence has become a symbol of the country’s inability to save a species on the verge of destruction.

The silence of the woods is familiar for the veteran biologist. For nearly three decades, Hobbs has watched the collapse of the species. He has tagged and tracked dozens of young owls who represented the hope of recovery. He has fed them mice in a futile effort to stave off death. His truck tyres have been slashed and the remains of a murdered spotted owl was once left on a tree stump as a threat.

“When I drive the highways and backroads here in their former range, all I see are ghosts,” he says. “The owls we’ve lost, I know their stories. And those stories are gone.”

For decades, the Canadian government and the province of British Columbia have fretted over the owls’ “catastrophic population decline”. The country’s environment minister has warned it faces “imminent threats to its survival” and a number of management plans have been drawn up, revised and reassessed amid community and scientific consultations.

The most recent identifies more than 300,000 hectares (740,000 acres) of protected habitat, but critics say is “completely watered down” and falls short because it withholds key areas from protection and still permits logging in old growth forests. Portions of old growth forest have been designated “future critical habitat” but only the designation “core critical habitat” triggers federal protections.

The cascade of failures, and the news this month that two more owls have died, raises the uncomfortable possibility that it might be too late for the northern spotted owl. [more]

‘All I see are ghosts’: fear and fury as the last spotted owl in Canada fights for survival