State of the Global Climate 2022: Sea level rise accelerates, European glacier melt shatters records, extreme weather causes devastation – “What climate scientists have warned about for decades is upon us”

By Seth Borenstein

6 November 2022

SHARM EL-SHEIKH, Egypt (AP) – Earth’s warming weather and rising seas are getting worse and doing so faster than before, the World Meteorological Organization warned Sunday in a somber note as world leaders started gathering for international climate negotiations. [Eight warmest years on record witness upsurge in climate change impacts –Des]

“The latest State of the Global Climate report is a chronicle of climate chaos,” United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said. “We must answer the planet’s distress signal with action — ambitious, credible climate action.”

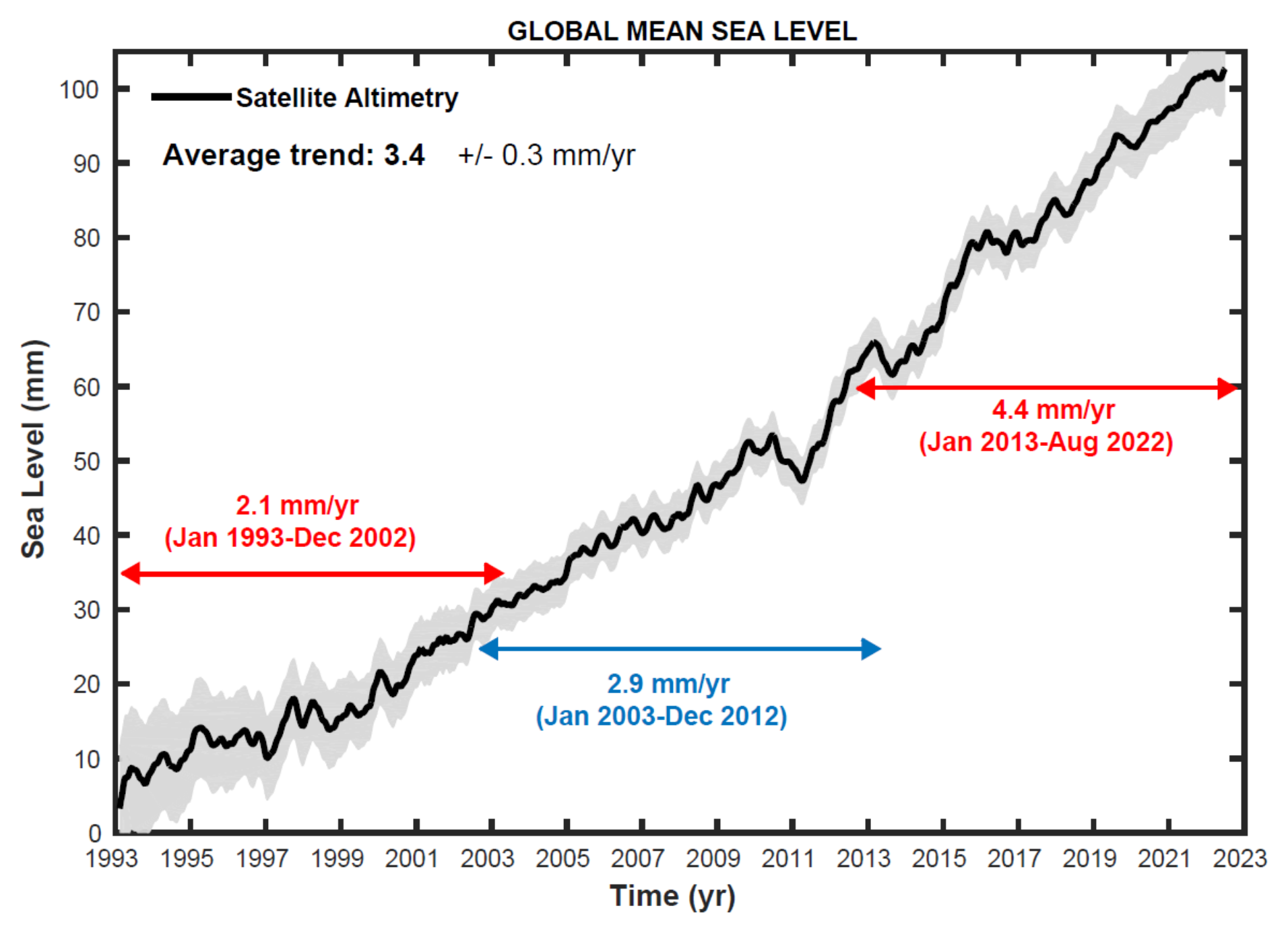

In its annual state of the climate report, the United Nations’ weather agency said that sea level rise in the past decade was double what it was in the 1990s and since January 2020 has jumped at a higher rate than that. Since the decade began, seas are rising at 5 millimeters a year (.2 inches) compared to 2.1 millimeters (.08 inches) in the 1990s.

The last eight years have been the warmest on record, the WMO said in a report that didn’t break new ground but was a collection of recent weather trends, data and impacts in one central place.

“The melting (of ice) game we have lost and also the sea level rate,” WMO chief Petteri Taalas told The Associated Press. “There are no positive indicators so far.”

The only reason that the globe hasn’t broken annual temperature records in the past few years is a rare three-year La Niña weather phenomenon, he said.

The data on sea level and average temperatures are nothing compared to how climate change has hit people in extreme weather. The report highlights the summer’s incredible flood in Pakistan that killed more than 1,700 people and displaced 7.9 million, a crippling four-year drought in East Africa that has more than 18 million hungry, the Yangtze River drying to its lowest level in August, and record heat-waves broiling people in Europe and China.

“This latest report from the World Meteorological Organization reads like a lab report for a critically ill patient, but in this case the patient is Earth,” said climate scientist Jennifer Francis of the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Cape Cod, who wasn’t part of the report.

Levels of heat-trapping carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide all reached record high levels, with potent methane increasing at a record pace, the report said.

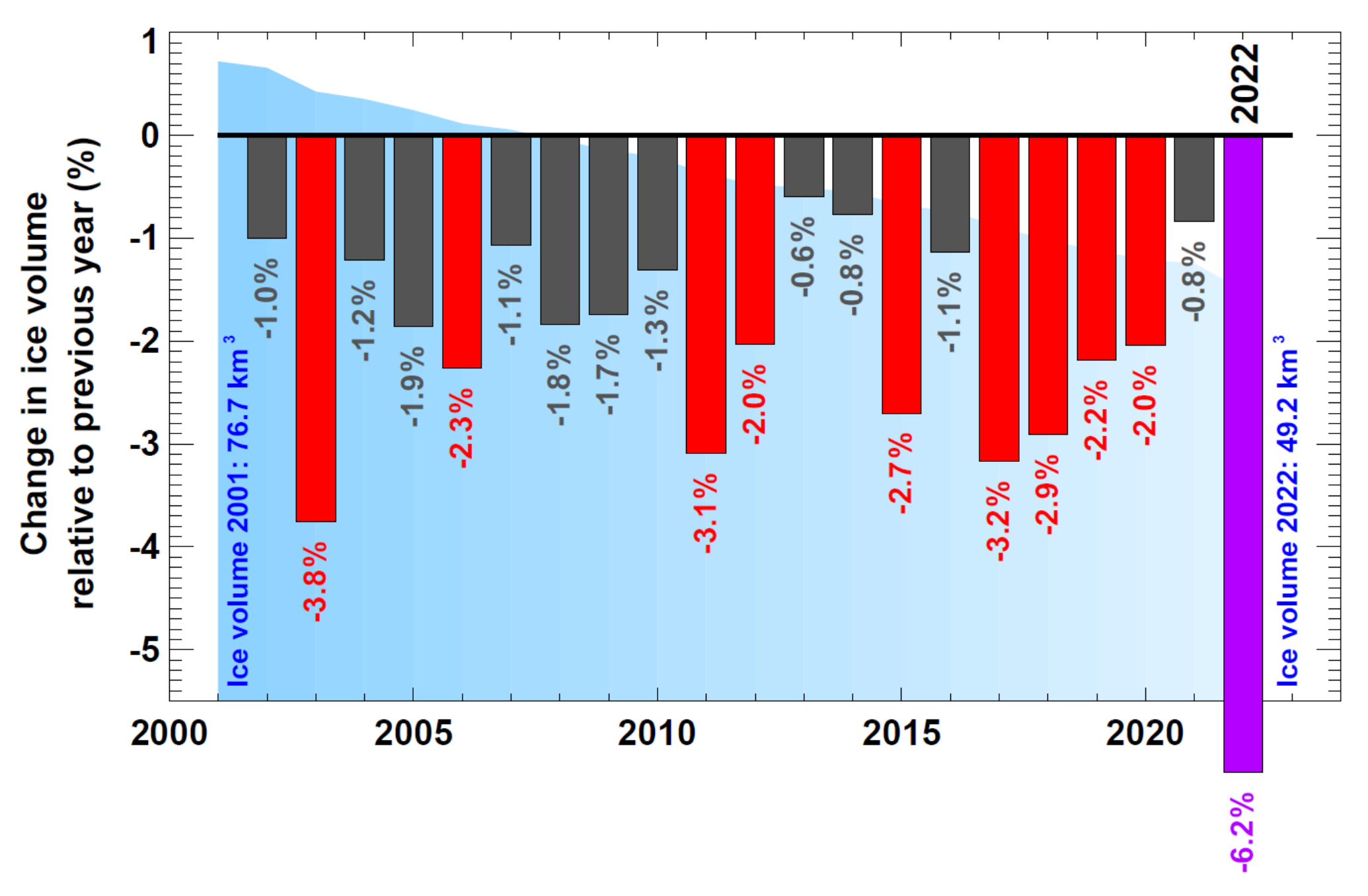

That means more than just warming temperatures on land. Ice, both Greenland’s ice sheet and the world’s glaciers, are shrinking precipitously, the report said. For the 26th year in a row, Greenland lost ice when all types of ice are factored in. The volume of glacier snow in Switzerland dropped by more than one-third from 2001 to 2022, the report said.

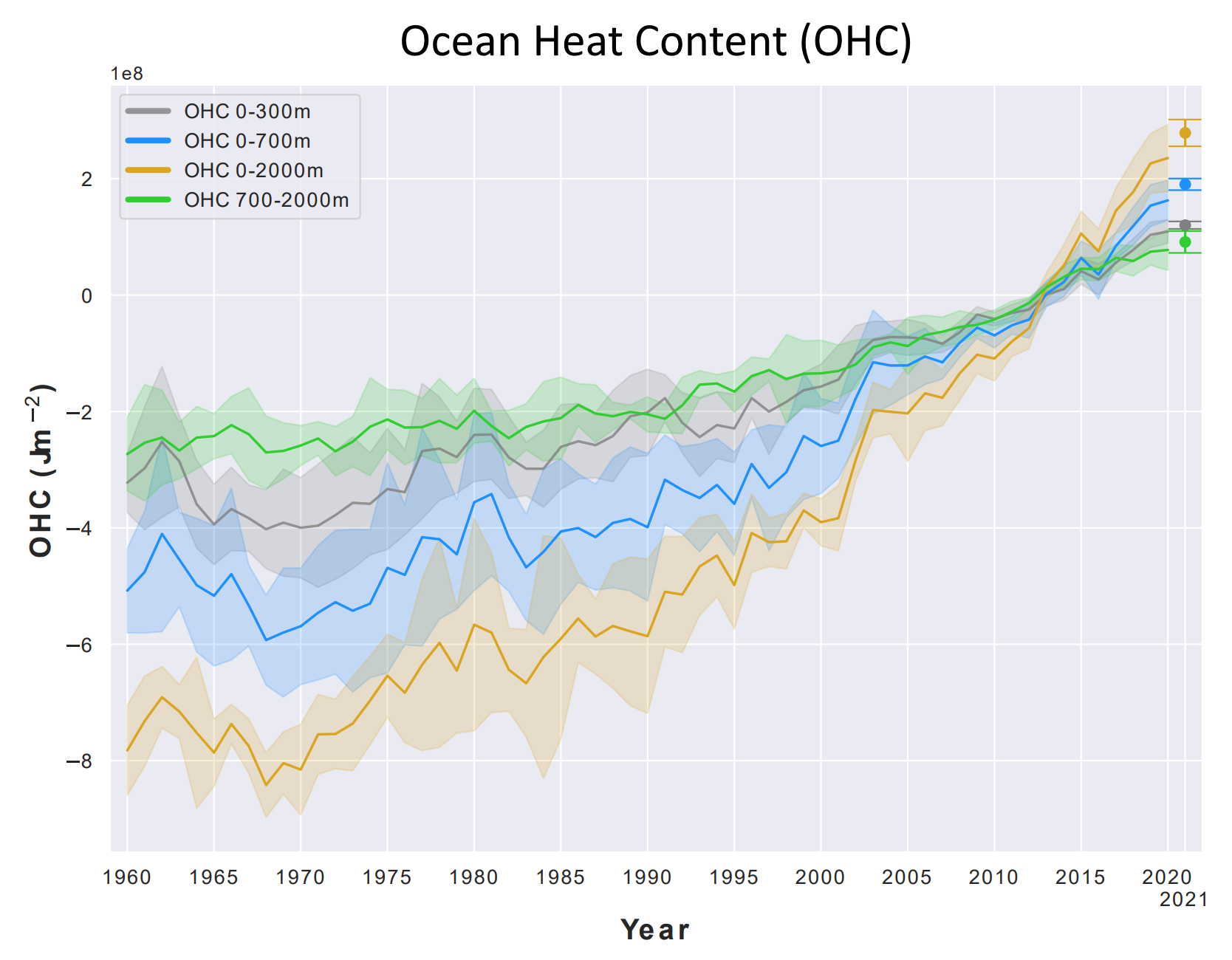

But 90% of the heat trapped on Earth goes into the ocean and the upper 2000 meters (6561 feet) of the ocean is getting warmer faster. The rate of warming the last 15 years is 67% faster than since 1971, the report said.

That ocean heat “will continue to warm in the future – a change which is irreversible on centennial to millennial time scales,” the report said.

Outside experts weren’t surprised by the report and said no one should be.

“What climate scientists have warned about for decades is upon us. And will continue to worsen without action,” said University of Georgia meteorology professor Marshall Shepherd. “Two things must go away: Climate delayism and speaking about climate change impacts in the future tense. It’s here.”

UN weather report: Climate woes bad and getting worse faster

Eight warmest years on record witness upsurge in climate change impacts

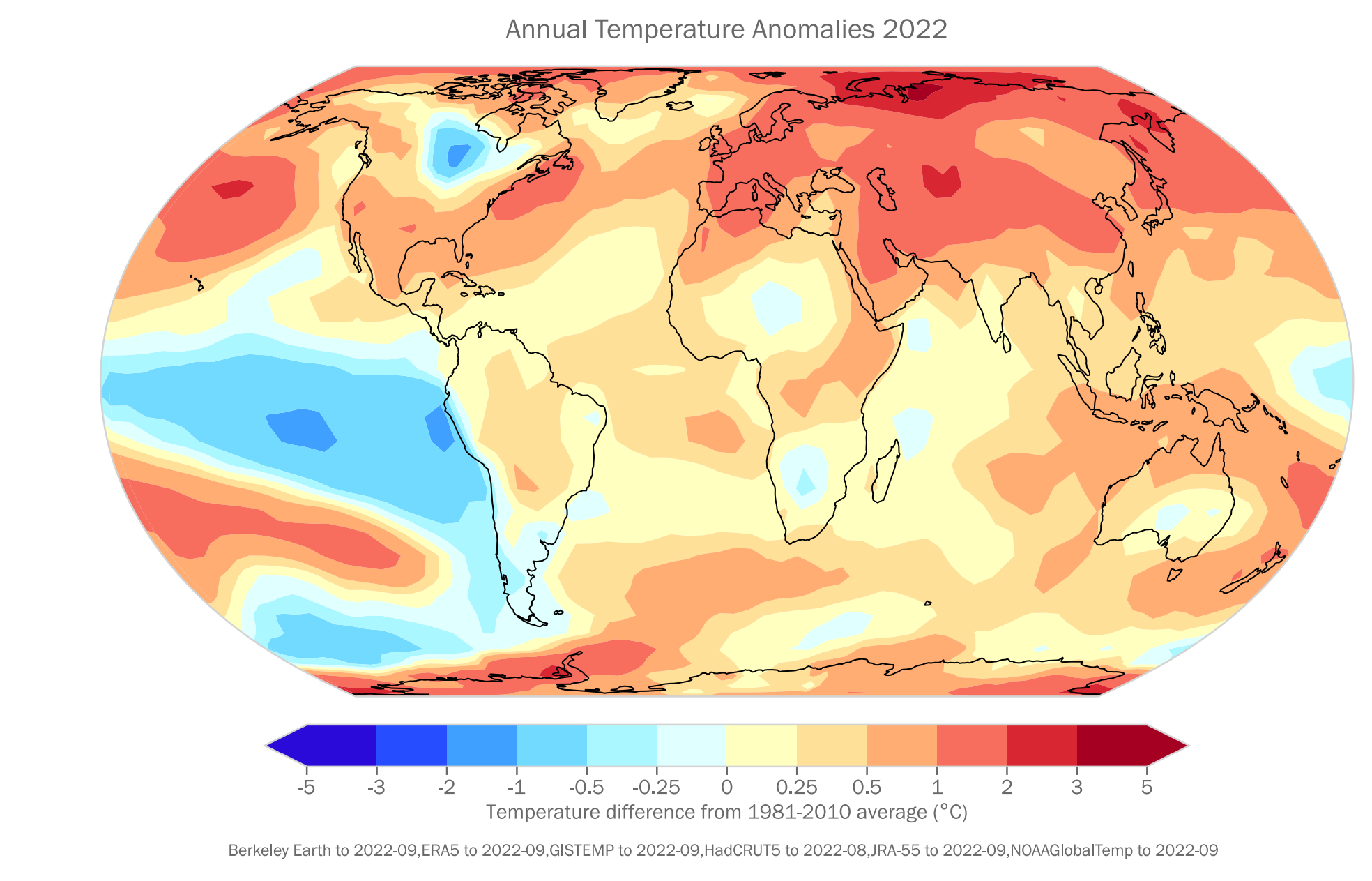

Sharm-El-Sheikh, Egypt 6 November (WMO) – The past eight years are on track to be the eight warmest on record, fuelled by ever-rising greenhouse gas concentrations and accumulated heat. Extreme heatwaves, drought, and devastating flooding have affected millions and cost billions this year, according to the World Meteorological Organization’s provisional State of the Global Climate in 2022 report.

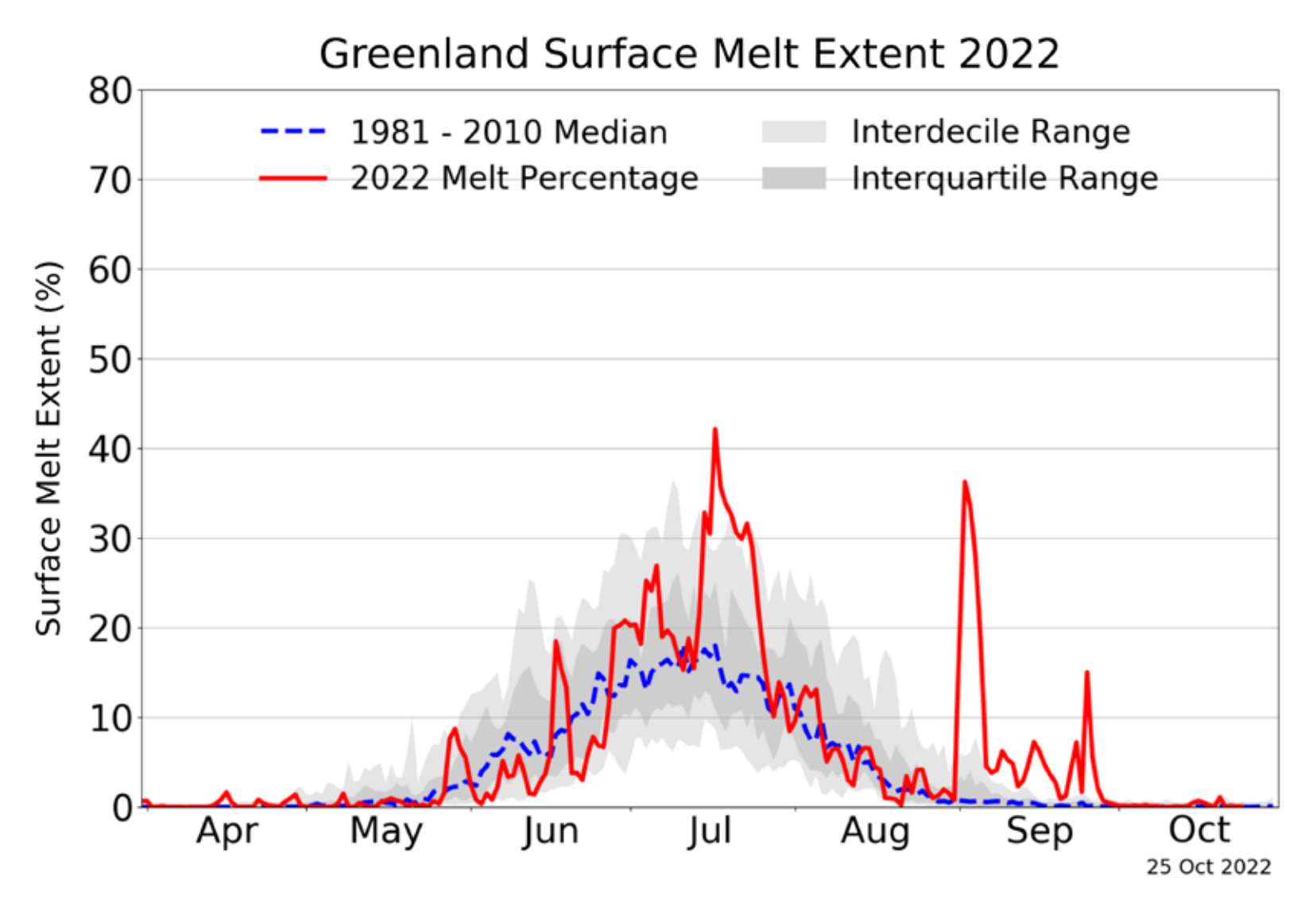

2022 took an exceptionally heavy toll on glaciers in the European Alps, with initial indications of record-shattering melt. The Greenland ice sheet lost mass for the 26th consecutive year and it rained (rather than snowed) there for the first time in September.

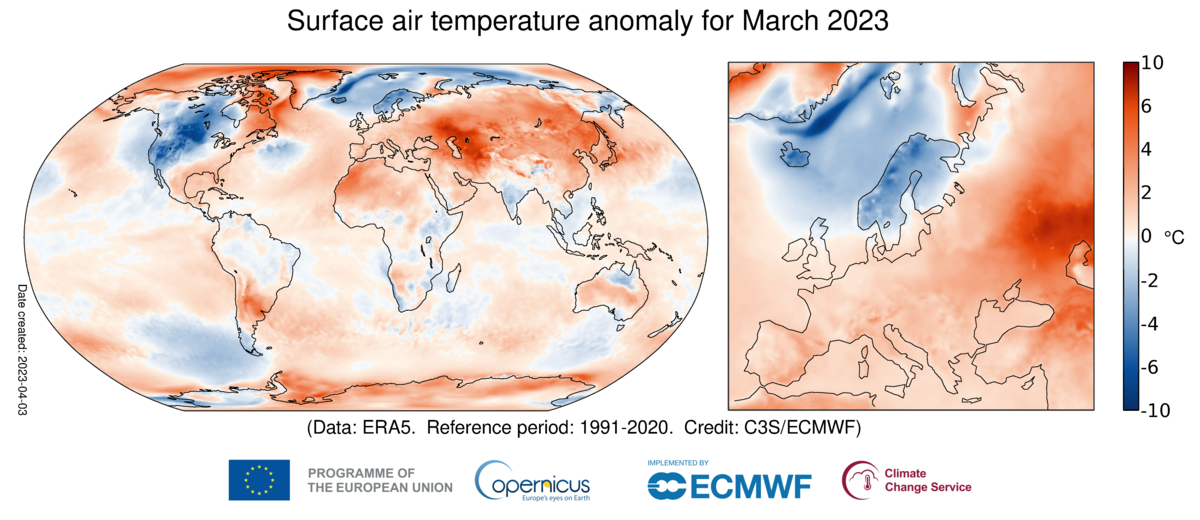

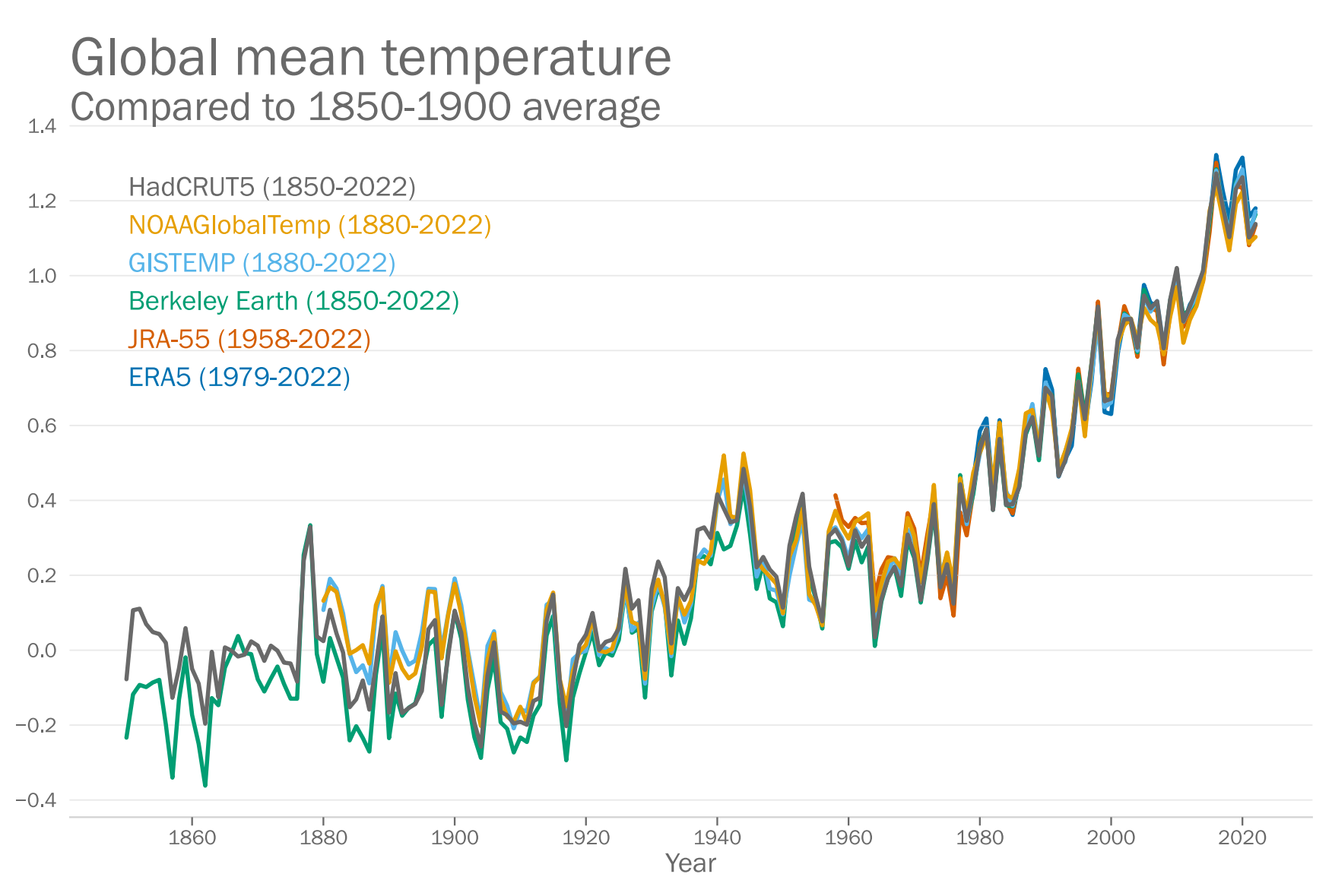

The global mean temperature in 2022 is currently estimated to be about 1.15 [1.02 to 1.28] °C above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average. A rare triple-dip cooling La Niña means that 2022 is likely to “only” be fifth or sixth warmest. However, this does not reverse the long-term trend; it is only a matter of time until there is another warmest year on record.

Indeed, the warming continues. The 10-year average for the period 2013-2022 is estimated to be 1.14 [1.02 to 1.27] °C above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial baseline. This compares with 1.09°C from 2011 to 2020, as estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment report.

Ocean heat was at record levels in 2021 (the latest year assessed), with the warming rate particularly high in the past 20 years.

“The greater the warming, the worse the impacts. We have such high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere now that the lower 1.5°C of the Paris Agreement is barely within reach,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof Petteri Taalas.

“It’s already too late for many glaciers and the melting will continue for hundreds if not thousands of years, with major implications for water security. The rate of sea level rise has doubled in the past 30 years. Although we still measure this in terms of millimetres per year, it adds up to half to one meter per century and that is a long-term and major threat to many millions of coastal dwellers and low-lying states,” he said.

“All too often, those least responsible for climate change suffer most – as we have seen with the terrible flooding in Pakistan and deadly, long-running drought in the Horn of Africa. But even well-prepared societies this year have been ravaged by extremes – as seen by the protracted heatwaves and drought in large parts of Europe and southern China,” said Prof. Taalas.

“Increasingly extreme weather makes it more important than ever to ensure that everyone on Earth has access to life-saving early warnings.”

WMO released the provisional State of the Global Climate report and an accompanying interactive storymap on the eve of the UN climate negotiations in Sharm-El-Sheikh, COP27. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres will unveil an Action Plan at COP27 to achieve Early Warnings for All in the next five years. Currently half the countries in the world lack these. Mr Guterres has asked WMO to spearhead the initiative.

The WMO State of the Global Climate report is produced annually. It provides an authoritative voice on the current state of the climate using key climate indicators and reporting on extreme events and their impacts. The temperature figures used in the provisional 2022 report are until the end of September. The final version will be issued next April.

Highlights

Concentrations of the main greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide – once again reached record levels in 2021. The annual increase in methane concentration was the highest on record. Data from key monitoring stations show atmospheric levels of the three gases continue to increase in 2022.

Temperature: The global average temperature in 2022 is estimated to be about 1.15 [1.02 to 1.28] °C above the 1850-1900 average. 2015 to 2022 are likely to be the eight warmest years on record. La Niña conditions have dominated since late 2020 and are expected to continue until the end of 2022. Continuing La Niña has kept global temperatures relatively «low» for the past two years – albeit higher than the last significant La Niña in 2011.

Glaciers and ice: In the European Alps, glacier melt records were shattered in 2022. Average thickness losses of between 3 and over 4 metres were measured throughout the Alps, substantially more than in the previous record year 2003.

In Switzerland, 6% of the glacier ice volume was lost between 2021 and 2022, according to initial measurements. For the first time in history, no snow outlasted the summer season even at the very highest measurement sites and thus no accumulation of fresh ice occurred. Between 2001 and 2022 the volume of glacier ice in Switzerland decreased from 77 km3 to 49 km3, a decline of more than a third.

A low snowpack at the end of winter and repeated coverings of Saharan dust set the scene for unprecedented ice loss between May and early September as a result of the long and intense heatwaves.

Global mean sea level has risen by an estimated 3.4 ± 0.3 mm per year over the 30 years (1993-2022) of the satellite altimeter record. The rate has doubled between 1993-2002 and 2013-2022 and sea level increased by about 5 mm between January 2021 and August 2022. The acceleration is due to increasing ice melt.

Ocean heat: The ocean stores around 90% of the accumulated heat from human emissions of greenhouse gases. The upper 2000m of the ocean continued to warm to record levels in 2021 (the latest year for which figures are available). Warming rates are especially high in the past two decades. It is expected that it will continue to warm in the future – a change which is irreversible on centennial to millennial time scales.

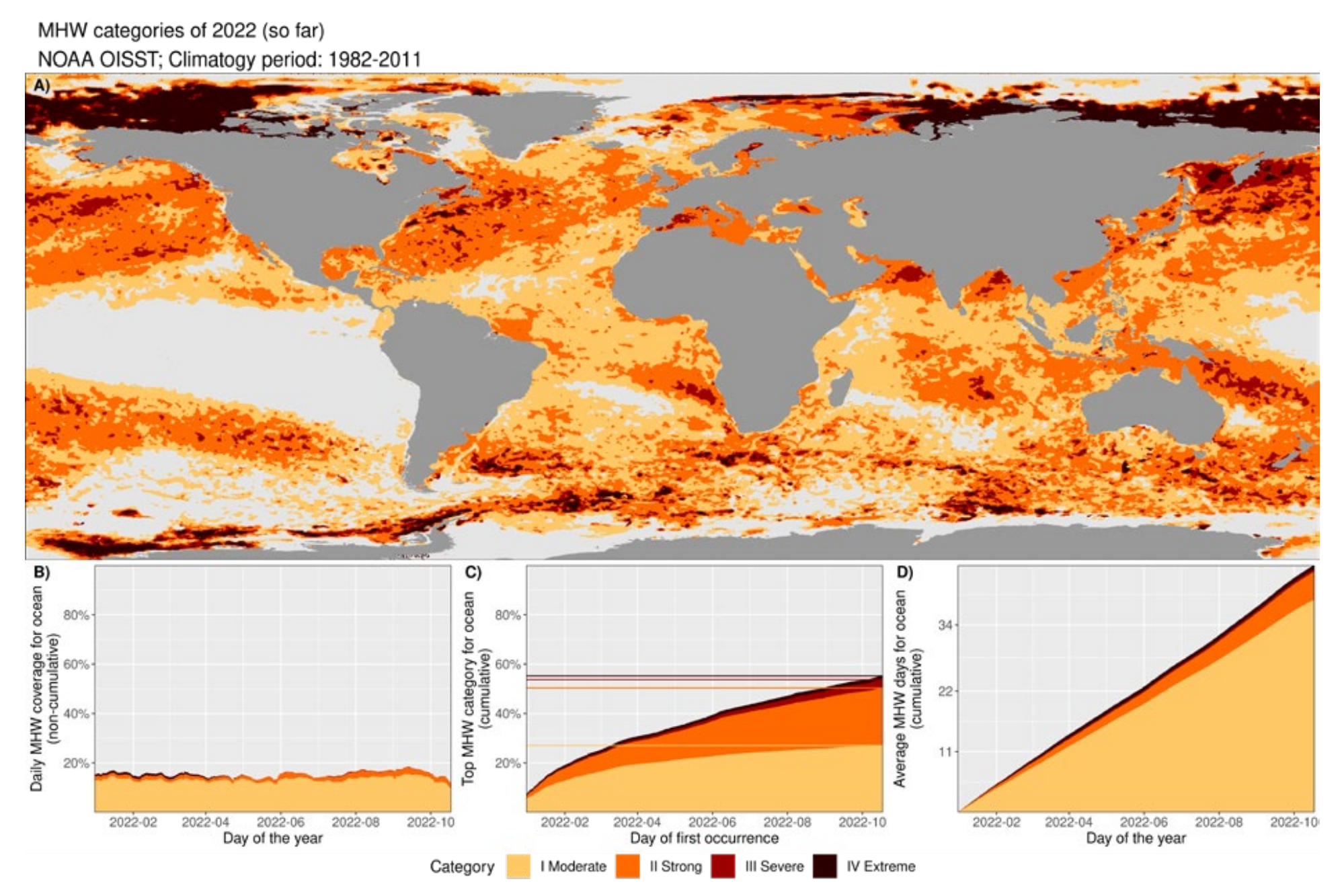

Overall, 55% of the ocean surface experienced at least one marine heatwave in 2022. In contrast only 22% of the ocean surface experienced a marine cold spell. Marine heatwaves are becoming more frequent, in contrast to cold waves.

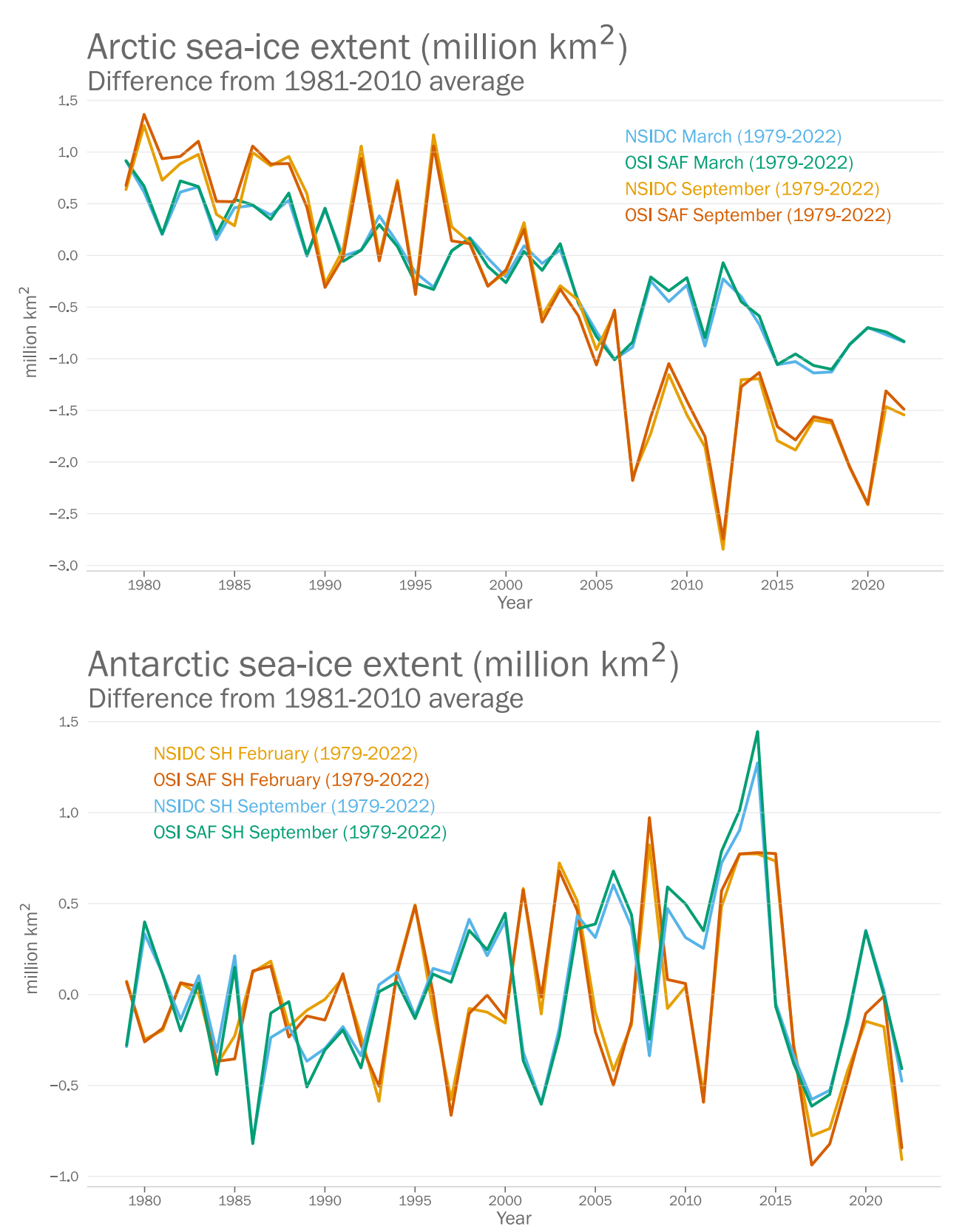

Arctic sea-ice extent was below the long-term (1981-2010) average for most of the year. The September extent was 4.87 million km2, or 1.54 million km2 below the long-term mean extent. Antarctic sea-ice extent dropped to 1.92 million km2 on 25 February, the lowest level on record and almost 1 million km2 below the long-term average.

Extreme weather: In East Africa, rainfall has been below average in four consecutive wet seasons, the longest in 40 years, with indications that the current season could also be dry. As a result of the persistent drought and other compounding factors, an estimated 18.4 to 19.3 million people faced food “Crisis” or worse levels of acute food insecurity before June 2022. Humanitarian agencies are warning that another below-average season will likely result in crop failure and further exacerbate the food insecurity situations in Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

Record breaking rain in July and August led to extensive flooding in Pakistan. There were at least 1 700 deaths and 33 million people affected. 7.9 million people were displaced. The flooding came hard on the heels of an extreme heatwave in March and April in both India and Pakistan.

The southern Africa region was battered by a series of cyclones over two months at the start of the year, hitting Madagascar hardest with torrential rain and devastating floods. Hurricane Ian caused extensive damage and loss of life in Cuba and southwest Florida in September.

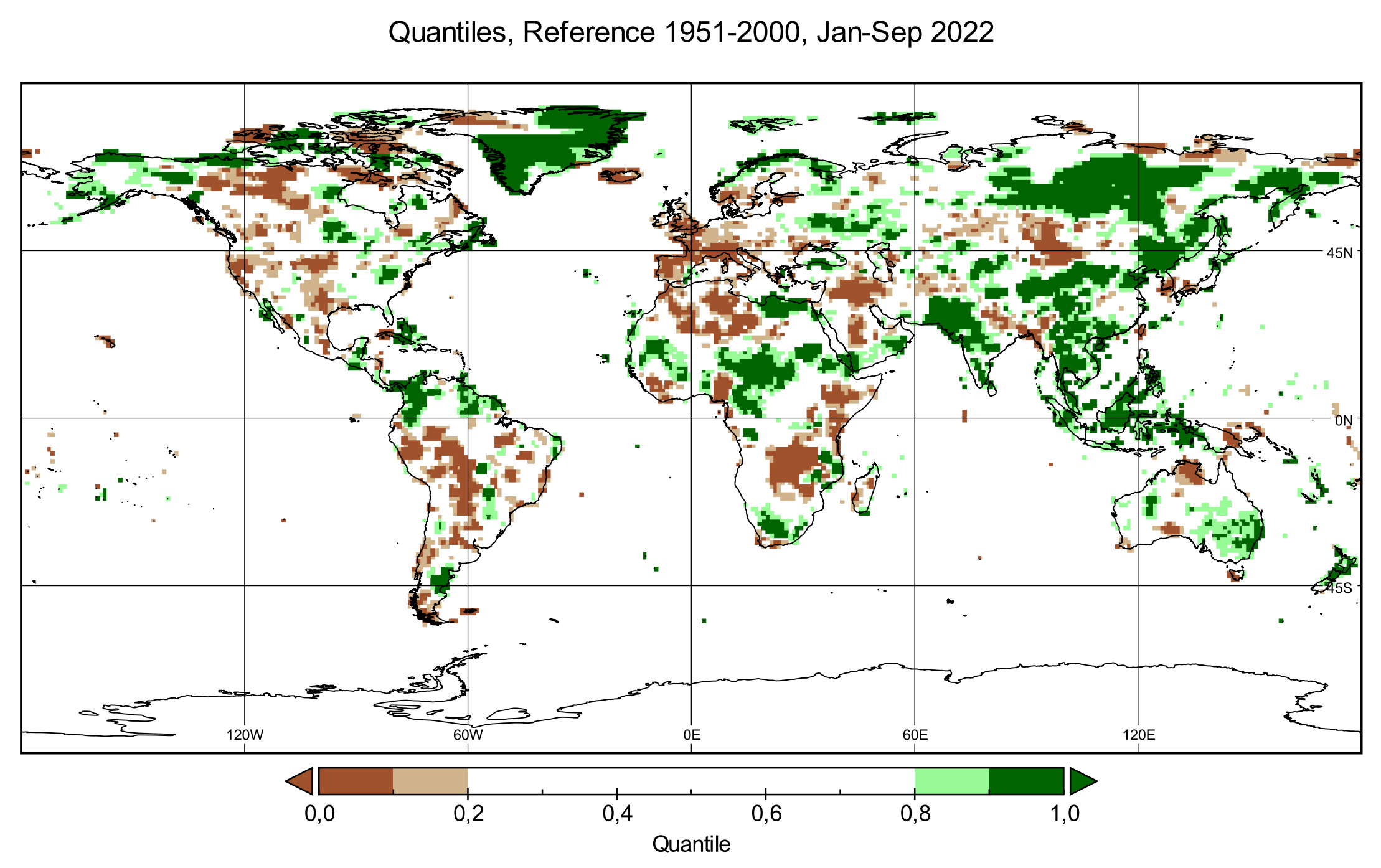

Large parts of the northern hemisphere were exceptionally hot and dry. China had the most extensive and long-lasting heatwave since national records began and the second-driest summer on record. The Yangtze River at Wuhan reached its lowest recorded level for August.

Large parts of Europe sweltered in repeated episodes of extreme heat. The United Kingdom saw a new national record on 19 July, when the temperature topped more than 40°C for the first time. This was accompanied by a persistent and damaging drought and wildfires. European rivers including the Rhine, Loire and Danube fell to critically low levels.

Contact

- Clare Nullis, WMO media officer, cnullis@wmo.int, Tel 41-79-7091397

Eight warmest years on record witness upsurge in climate change impacts