Sea level rise is killing trees along the Atlantic coast, creating “ghost forests” that are visible from space

By Emily Ury

6 April 2021

(The Conversation) – Trekking out to my research sites near North Carolina’s Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, I slog through knee-deep water on a section of trail that is completely submerged. Permanent flooding has become commonplace on this low-lying peninsula, nestled behind North Carolina’s Outer Banks. The trees growing in the water are small and stunted. Many are dead.

Throughout coastal North Carolina, evidence of forest die-off is everywhere. Nearly every roadside ditch I pass while driving around the region is lined with dead or dying trees.

As an ecologist studying wetland response to sea level rise, I know this flooding is evidence that climate change is altering landscapes along the Atlantic coast. It’s emblematic of environmental changes that also threaten wildlife, ecosystems, and local farms and forestry businesses.

Like all living organisms, trees die. But what is happening here is not normal. Large patches of trees are dying simultaneously, and saplings aren’t growing to take their place. And it’s not just a local issue: Seawater is raising salt levels in coastal woodlands along the entire Atlantic Coastal Plain, from Maine to Florida. Huge swaths of contiguous forest are dying. They’re now known in the scientific community as “ghost forests.”

The insidious role of salt

Sea level rise driven by climate change is making wetlands wetter in many parts of the world. It’s also making them saltier.

In 2016 I began working in a forested North Carolina wetland to study the effect of salt on its plants and soils. Every couple of months, I suit up in heavy rubber waders and a mesh shirt for protection from biting insects, and haul over 100 pounds of salt and other equipment out along the flooded trail to my research site. We are salting an area about the size of a tennis court, seeking to mimic the effects of sea level rise.

After two years of effort, the salt didn’t seem to be affecting the plants or soil processes that we were monitoring. I realized that instead of waiting around for our experimental salt to slowly kill these trees, the question I needed to answer was how many trees had already died, and how much more wetland area was vulnerable. To find answers, I had to go to sites where the trees were already dead.

Rising seas are inundating North Carolina’s coast, and saltwater is seeping into wetland soils. Salts move through groundwater during phases when freshwater is depleted, such as during droughts. Saltwater also moves through canals and ditches, penetrating inland with help from wind and high tides. Dead trees with pale trunks, devoid of leaves and limbs, are a telltale sign of high salt levels in the soil. A 2019 report called them “wooden tombstones.”

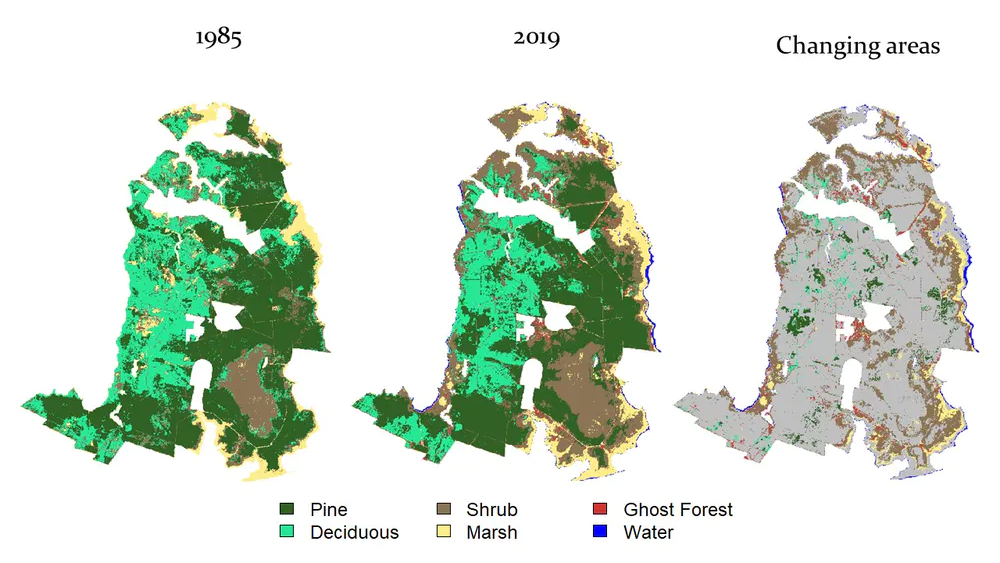

As the trees die, more salt-tolerant shrubs and grasses move in to take their place. In a newly published study that I coauthored with Emily Bernhardt and Justin Wright at Duke University and Xi Yang at the University of Virginia, we show that in North Carolina this shift has been dramatic.

The state’s coastal region has suffered a rapid and widespread loss of forest, with cascading impacts on wildlife, including the endangered red wolf and red-cockaded woodpecker. Wetland forests sequester and store large quantities of carbon, so forest die-offs also contribute to further climate change. [more]

One Response

Comments are closed.