Great Wall of Lights: China’s sea power on Darwin’s doorstep – “It really is like the Wild West. Nobody is responsible for enforcement out there.”

By Joshua Goodman

24 September 2021

ABOARD THE OCEAN WARRIOR in the eastern Pacific Ocean (AP) – It’s 3 a.m., and after five days plying through the high seas, the Ocean Warrior is surrounded by an atoll of blazing lights that overtakes the nighttime sky.

“Welcome to the party!” says third officer Filippo Marini as the spectacle floods the ship’s bridge and interrupts his overnight watch.

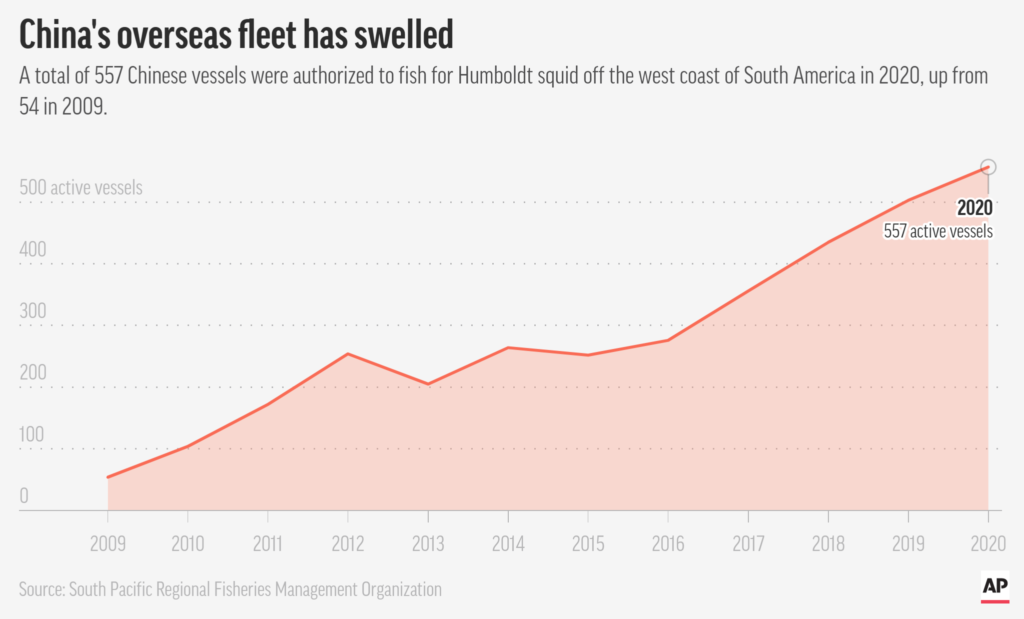

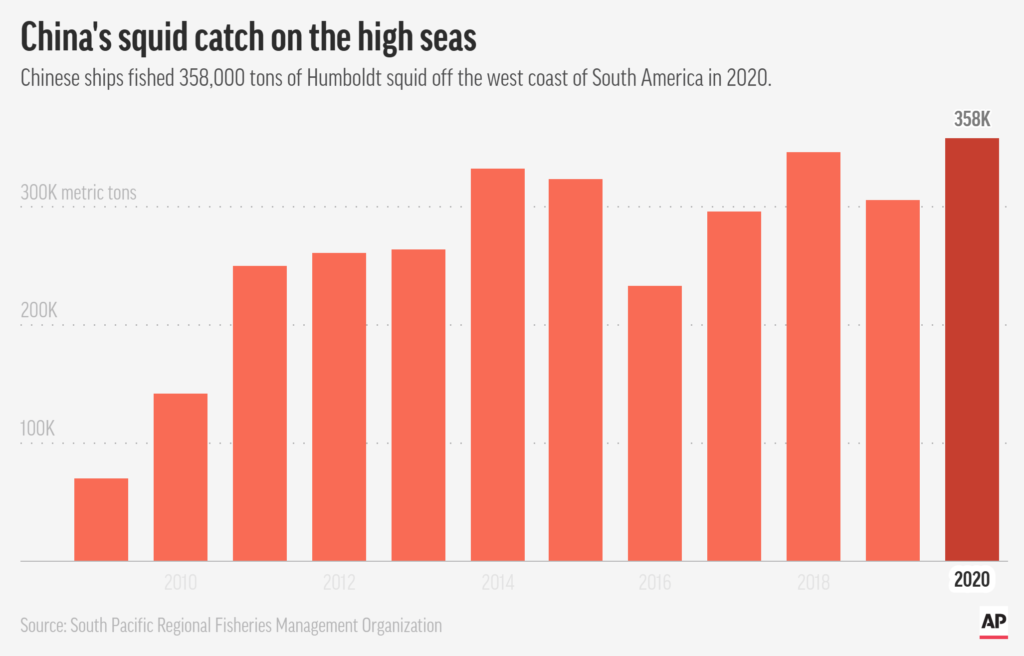

It’s the conservationists’ first glimpse of the world’s largest fishing fleet: an armada of nearly 300 Chinese vessels that have sailed halfway across the globe to lure the elusive Humboldt squid from the Pacific Ocean’s inky depths.

As Italian hip hop blares across the bridge, Marini furiously scribbles the electronic IDs of 37 fishing vessels that pop up as green triangles on the Ocean Warrior’s radar onto a sheet of paper, before they disappear.

Immediately he detects a number of red flags: two of the boats have gone ‘dark,’ their mandatory tracking device that gives a ship’s position switched off. Still others are broadcasting two different radio numbers — a sign of possible tampering.

The Associated Press with Spanish-language broadcaster Univision accompanied the Ocean Warrior this summer on an 18-day voyage to observe up close for the first time the Chinese distant water fishing fleet on the high seas off South America.

The vigilante patrol was prompted by an international outcry last summer when hundreds of Chinese vessels were discovered fishing for squid near the long-isolated Galapagos Islands, a UNESCO world heritage site that inspired 19th-century naturalist Charles Darwin and is home to some of the world’s most endangered species, from giant tortoises to hammerhead sharks.

China’s deployment to this remote expanse is no accident. Decades of overfishing have pushed its overseas fleet, the world’s largest, ever farther from home. Officially capped at 3,000 vessels, the fleet might actually consist of thousands more. Keeping such a sizable flotilla at sea, sometimes for years at a time, is at once a technical feat made possible through billions in state subsidies and a source of national pride akin to what the U.S. space program was for generations of Americans.

Beijing says it has zero tolerance for illegal fishing and points to recent actions such as a temporary moratorium on high seas squid fishing as evidence of its environmental stewardship. Those now criticizing China, including the U.S. and Europe, for decades raided the oceans themselves.

Beijing is exporting its overfishing problem to South America. China is chiefly responsible for the plunder of shark and tuna in Asia. With that track record, are we really supposed to believe they will manage this new fishery responsibly? It really is like the Wild West. Nobody is responsible for enforcement out there.

Captain Peter Hammarstedt, director of campaigns for Sea Shepherd

But the sheer size of the Chinese fleet and its recent arrival to the Americas has stirred fears that it could exhaust marine stocks. There’s also concern that in the absence of effective controls, illegal fishing will soar. The U.S. Coast Guard recently declared that illegal fishing had replaced piracy as its top maritime security threat.

Meanwhile, activists are seeking restrictions on fishing as part of negotiations underway on a first-ever High Seas Treaty, which could dramatically boost international cooperation on the traditionally lawless waters that comprise nearly half of the planet.

Of the 30 vessels the AP observed up close, 24 had a history of labor abuse accusations, past convictions for illegal fishing or showed signs of possibly violating maritime law. Collectively, these issues underscore how the open ocean around the Americas — where the U.S. has long dominated and China is jockeying for influence — have become a magnet for the seafood industry’s worst offenders.

Specifically, 16 ships either sailed with their mandatory safety transponders turned off, broadcast multiple electronic IDs or transmitted information that didn’t match its listed name or location — discrepancies that are often associated with illegal fishing, although the AP saw no evidence that they were engaged in illicit activity.

Six ships were owned by companies accused of forced labor including one vessel, the Chang Tai 802, whose Indonesian crew said they had been stuck at sea for years.

Another nine ships face accusations of illegal fishing elsewhere in the world while one giant fuel tanker servicing the fleet, the Ocean Ruby, is operated by the affiliate of a company suspected of selling fuel to North Korea in violation of United Nations sanctions. Yet another, the Fu Yuan Yu 7880, is operated by an affiliate of a Nasdaq-traded company, Pingtan Marine Enterprise, whose Chinese executives had their U.S. visas cancelled for alleged links to human trafficking.

“Beijing is exporting its overfishing problem to South America,” said Captain Peter Hammarstedt, director of campaigns for Sea Shepherd, a Netherlands-based ocean conservation group that operates nine well-equipped vessels, including the Ocean Warrior.

“China is chiefly responsible for the plunder of shark and tuna in Asia,” says Hammarstedt, who organized the high seas campaign, called Operation Distant Water, after watching how illegal Chinese vessels ravaged poor fishing villages in West Africa. “With that track record, are we really supposed to believe they will manage this new fishery responsibly?” […]

“It really is like the Wild West,” said Hammarstedt. “Nobody is responsible for enforcement out there.” [more]

Great Wall of Lights: China’s sea power on Darwin’s doorstep