Global apathy toward the fires in Australia is a scary portent for the future

By David Wallace-Wells

31 December 2019

(New York magazine) – Right now, on the outskirts of a hyper modern first world megapolis, at the end of a year in which the public seemed finally to wake up to the dramatic threat from global warming, a climate disaster of unimaginable horror has been unfolding for almost two full months, and the rest of the world is hardly paying attention.

The New South Wales fires have been burning since September 2019, destroying fifteen million acres (or more than two thousand square miles) [15 million acres is actually more than 23,000 square miles, as spotted by reader John C. Wilson. Thanks, John! –Des] and remain almost entirely uncontrolled by the volunteer firefighting forces deployed to stop them; on 12 November 2019, greater Sydney declared an unprecedented “catastrophic” fire warning. That was six weeks ago, and the blazes are almost certain to continue burning through the end of next month, the soonest real rain might arrive. They may last longer still, of course, aided in part by record-breaking heat waves that are simultaneously punishing the country (technically an entire continent, Australia as a whole averaged more than 100 Fahrenheit earlier this month) and devastating marine life in the surrounding ocean. “On land, Australia’s rising heat is ‘apocalyptic,” the Straits-Times of Singapore wrote. “In the ocean, it’s even worse.”

Already, smoke has enveloped the city of Sydney in air at least ten times as thick with smoke as is considered safe to breathe, setting off indoor fire alarms and suspending the city’s ferry service, since the boats couldn’t navigate the smog. The city of Melbourne, more than 500 miles away, has been choked by smoke, as well, and the glaciers all the way in New Zealand have changed color because of the fires, too. An early report that koalas were made “functionally extinct” turned out to have been erroneous, but a more recent report suggests that, due to the bushfires, 480 million animals have died. And because plants contain carbon which is released when burned, when the New South Wales fires finally do burn out, they almost certainly will have doubled Australia’s national carbon emissions for the year — or more.

You could pick almost any day from the last two months and be horrified by the images of that day’s burning. But on the eve of the new year, something about the random sampling that’s shown up in my social media feed seems especially harrowing. […]

The duration of this climate horror has allowed us to normalize it even while it continues to unfold — continues to torture, and brutalize, and terrify. The Camp Fire in Paradise, California did almost all of its damage in just four hours, and the short duration may have been as important to our collective horror as the speed. Perhaps if it had lasted longer, even burning with equal ferocity, we would nevertheless simply have gotten used to it as the white noise of catastrophe all around us, as impossible as that may seem to imagine, given the scale of suffering involved.

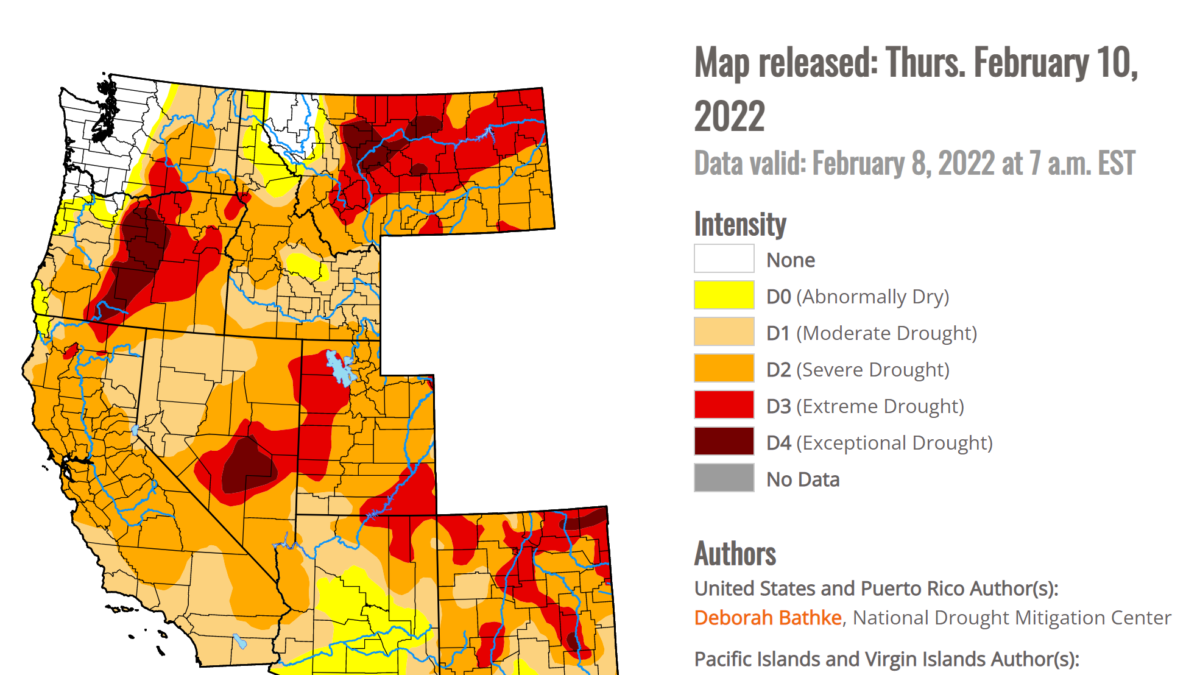

This hypothesis is especially concerning, of course, given the way that climate change will inevitably extend these sorts of horrors in the decades ahead. Today, there are categories of natural disasters, like droughts, we understand can last for months, or even years, and though they should demand our attention, rarely do. Already, we have added to that category disasters like the flooding that walloped the Midwest this spring — lasting many months in some places, preventing American farmers from planting crops on 19 million acres. But wrapping your head around flooding as an enduring, months-long disaster is one thing, however unthinkable it might have been to the average American five or ten years ago. Coming to see the wildfire season as a permanent threat is another terrifying adjustment, though Californians are now doing precisely that. But regarding the fires themselves — which can travel 60 miles per hour or more, creating their own weather systems that project lightning strikes miles away from the blaze, causing more fire — not as a sudden catastrophe but a semi-permanent condition strikes me as another level of normalization entirely. And yet here we are. [more]

Global Apathy Toward the Fires in Australia Is a Scary Portent for the Future

Please check your math. 15 million acres is over 23,000 square miles. It is not merely 2000 square miles. Innumeracy is a constant in this type of reporting. Any pairing of numbers should automatically be fact checked.

Well spotted! I’ve updated the post with a correction.