World must cut carbon emissions by 7.6 percent every year for next decade to meet 1.5°C Paris target – “It is very disturbing that in spite of the many warnings, global emissions have continued to increase and do not seem to be likely to peak anytime soon”

GENEVA, 26 November 2019 (UNEP) – On the eve of a year in which nations are due to strengthen their Paris climate pledges, a new UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report warns that unless global greenhouse gas emissions fall by 7.6 per cent each year between 2020 and 2030, the world will miss the opportunity to get on track towards the 1.5°C temperature goal of the Paris Agreement.

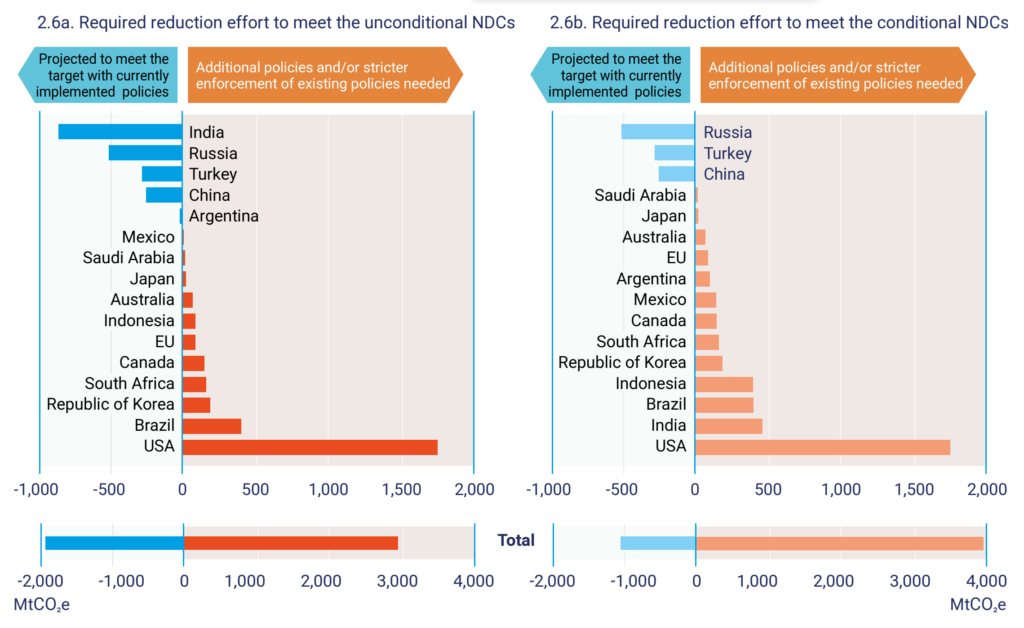

UNEP’s annual Emissions Gap Report says that even if all current unconditional commitments under the Paris Agreement are implemented, temperatures are expected to rise by 3.2°C, bringing even wider-ranging and more destructive climate impacts. Collective ambition must increase more than fivefold over current levels to deliver the cuts needed over the next decade for the 1.5°C goal.

2020 is a critical year for climate action, with the UN climate change conference in Glasgow aiming to determine the future course of efforts to avert crisis, and countries expected to significantly step up their climate commitments.

“For ten years, the Emissions Gap Report has been sounding the alarm – and for ten years, the world has only increased its emissions,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres. “There has never been a more important time to listen to the science. Failure to heed these warnings and take drastic action to reverse emissions means we will continue to witness deadly and catastrophic heatwaves, storms, and pollution.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that going beyond 1.5°C will increase the frequency and intensity of climate impacts.

“Our collective failure to act early and hard on climate change means we now must deliver deep cuts to emissions – over 7 per cent each year, if we break it down evenly over the next decade,” said Inger Andersen, UNEP’s Executive Director. “This shows that countries simply cannot wait until the end of 2020, when new climate commitments are due, to step up action. They – and every city, region, business and individual – need to act now.”

“We need quick wins to reduce emissions as much as possible in 2020, then stronger Nationally Determined Contributions to kick-start the major transformations of economies and societies. We need to catch up on the years in which we procrastinated,” she added. “If we don’t do this, the 1.5°C goal will be out of reach before 2030.”

G20 nations collectively account for 78 per cent of all emissions, but only five G20 members have committed to a long-term zero emissions target.

“The transformation is starting small but is expanding fast. We find that in all areas, some actors are taking truly ambitions actions. For example, zero emission targets and targets of 100 per cent renewables are spreading fast, but also commitments for zero emissions in heavy industry start to emerge unthinkable only a few years ago. What is necessary now is a global rollout of the front runner examples.”

Niklas Höhne, founding partner NewClimate Institute

In the short-term, developed countries will have to reduce their emissions quicker than developing countries, for reasons of fairness and equity. However, all countries will need to contribute more to collective effects. Developing countries can learn from successful efforts in developed countries; they can even leapfrog them and adopt cleaner technologies at a faster rate.

Crucially, the report says all nations must substantially increase ambition in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), as the Paris commitments are known, in 2020 and follow up with policies and strategies to implement them. Solutions are available to make meeting the Paris goals possible, but they are not being deployed fast enough or at a sufficiently large scale.

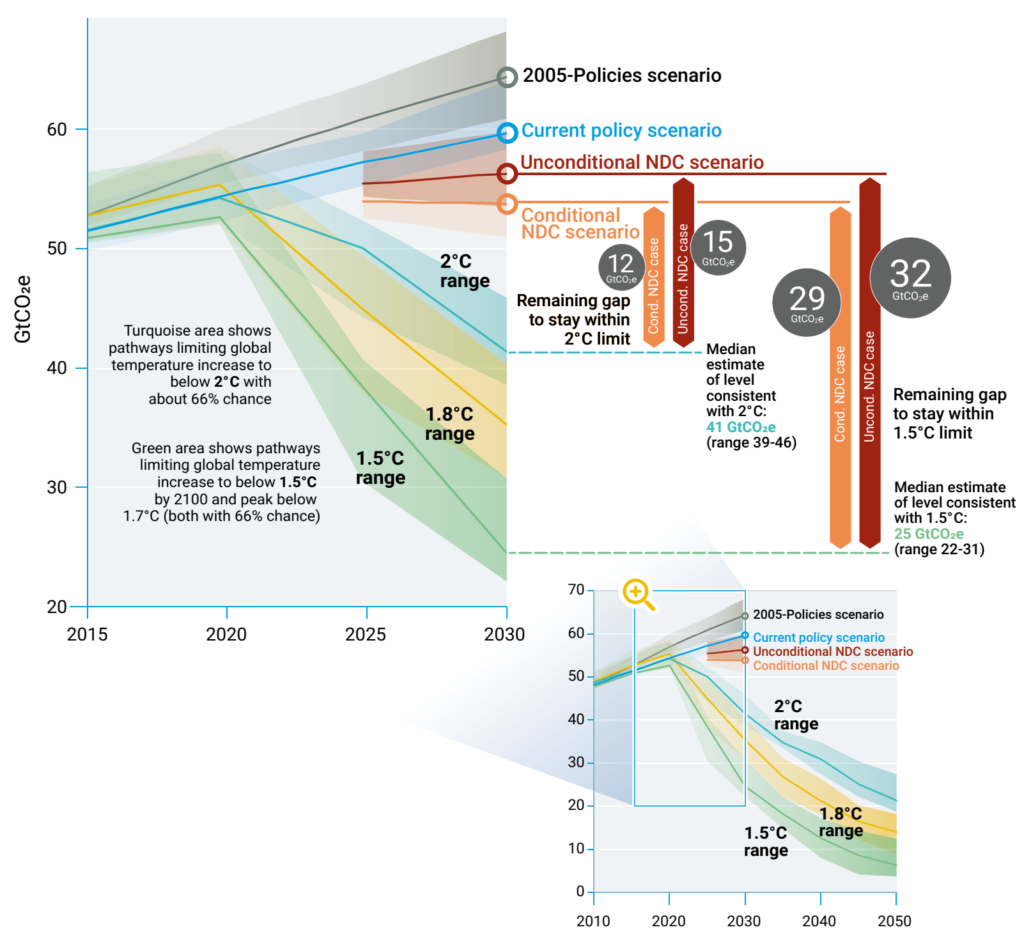

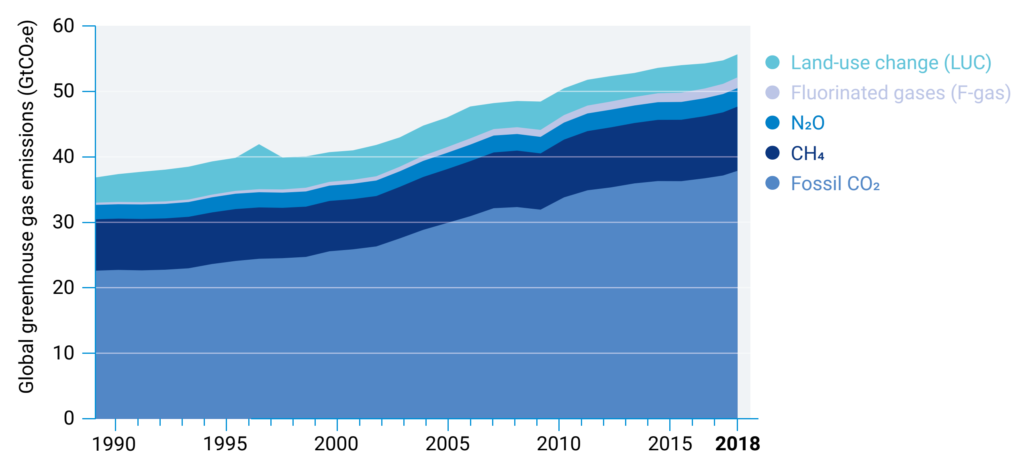

Each year, the Emissions Gap Report assesses the gap between anticipated emissions in 2030 and levels consistent with the 1.5°C and 2°C targets of the Paris Agreement. The report finds that greenhouse gas emissions have risen 1.5 per cent per year over the last decade. Emissions in 2018, including from land-use changes such as deforestation, hit a new high of 55.3 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent.

To limit temperatures, annual emissions in 2030 need to be 15 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent lower than current unconditional NDCs imply for the 2°C goal; they need to be 32 gigatonnes lower for the 1.5°C goal. On an annual basis, this means cuts in emissions of 7.6 per cent per year from 2020 to 2030 to meet the 1.5°C goal and 2.7 per cent per year for the 2°C goal.

To deliver on these cuts, the levels of ambition in the NDCs must increase at least fivefold for the 1.5°C goal and threefold for the 2°C.

“When looking back at the 10 years we have prepared the Emissions Gap Report, it is very disturbing that in spite of the many warnings, global emissions have continued to increase and do not seem to be likely to peak anytime soon. The reductions required can only be achieved by transforming the energy sector. The good news is that since wind and solar in most places have become the cheapest source of electricity, the main challenges now is to design and implement an integrated, decentralised power system.”

John Christensen, Director of UNEP DTU Partnership

Climate change can still be limited to 1.5°C, the report says. There is increased understanding of the additional benefits of climate action – such as clean air and a boost to the Sustainable Development Goals. There are many ambitious efforts from governments, cities, businesses and investors. Solutions, and the pressure and will to implement them, are abundant.

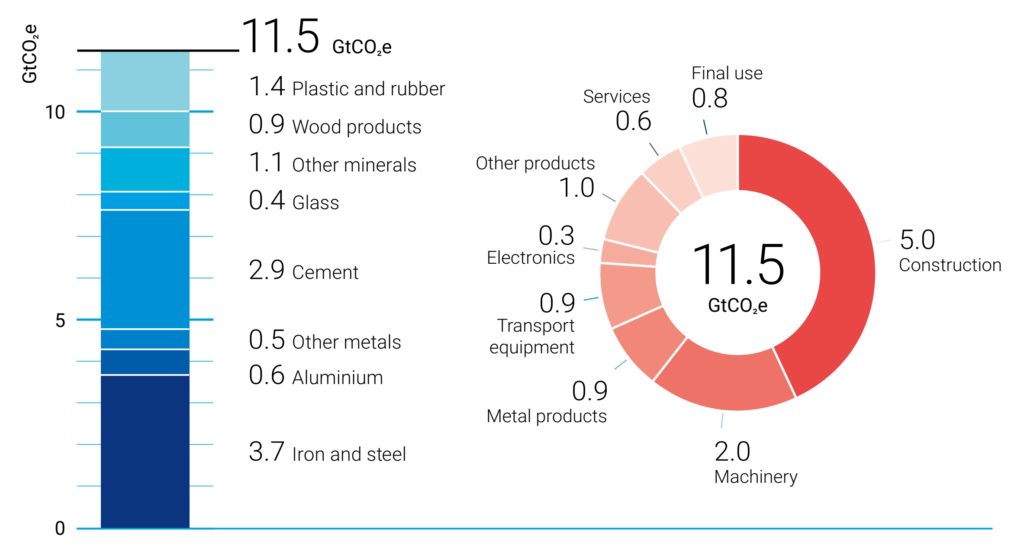

As it does each year, the report focuses on the potential of selected sectors to deliver emissions cuts. This year it looks at the energy transition and the potential of efficiency in the use of materials, which can go a long way to closing the emissions gap.

Contact

- Keishamaza Rukikaire, Head of News & Media, UN Environment Programme, +254717080753

- Alejandro Laguna Lopez, Europe Information Officer, UN Environment Programme.

Climate ‘catastrophe-check’ for UN Aid Agencies – John Doyle

This is a must watch video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Deaz3UN0rw