Arctic shifts to a carbon source due to winter soil emissions – “The warmer it gets, the more carbon will be released into the atmosphere from the permafrost region, which will add to further warming”

By Samson Reiny

8 November 2019

(NASA) – A NASA-funded study suggests winter carbon emissions in the Arctic may be adding more carbon into the atmosphere each year than is taken up by Arctic vegetation, marking a stark reversal for a region that has captured and stored carbon for tens of thousands of years.

The study, published 21 October 2019 in Nature Climate Change, warns that winter carbon dioxide loss from the world’s permafrost regions could increase by 41% over the next century if human-caused greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current pace. Carbon emitted from thawing permafrost has not been included in the majority of models used to predict future climates.

Permafrost is the carbon-rich frozen soil that covers 24% of Northern Hemisphere land area, encompassing vast stretches of territory across Alaska, Canada, Siberia and Greenland. Permafrost holds more carbon than has ever been released by humans via fossil fuel combustion, and this permafrost has kept carbon safely locked away in an icy embrace for tens of thousands of years. But as global temperatures warm, permafrost is thawing and releasing greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

“These findings indicate that winter carbon dioxide loss may already be offsetting growing season carbon uptake, and these losses will increase as the climate continues to warm,” said Woods Hole Research Center Arctic Program Director Sue Natali, lead author of the study. “Studies focused on individual sites have seen this transition, but until now we haven’t had a clear accounting of the winter carbon balance throughout the entire Arctic region.”

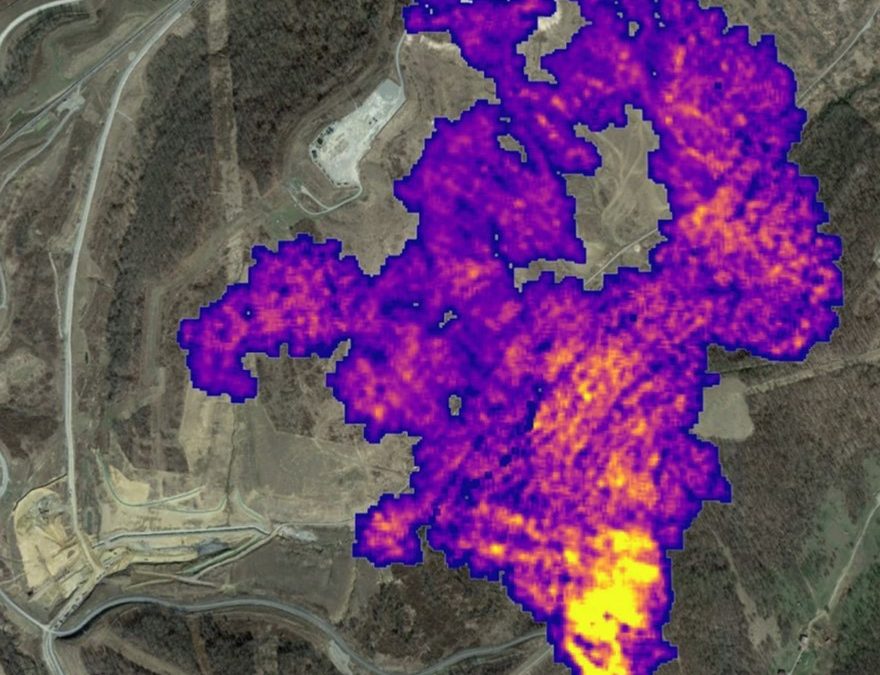

This study was supported by NASA’s Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) and conducted in coordination with the Permafrost Carbon Network and more than 50 collaborating institutions. In addition to space-based observations of Earth’s changing environment, NASA sponsors scientific field campaigns to advance our understanding of how our climate is changing and could change in the future.

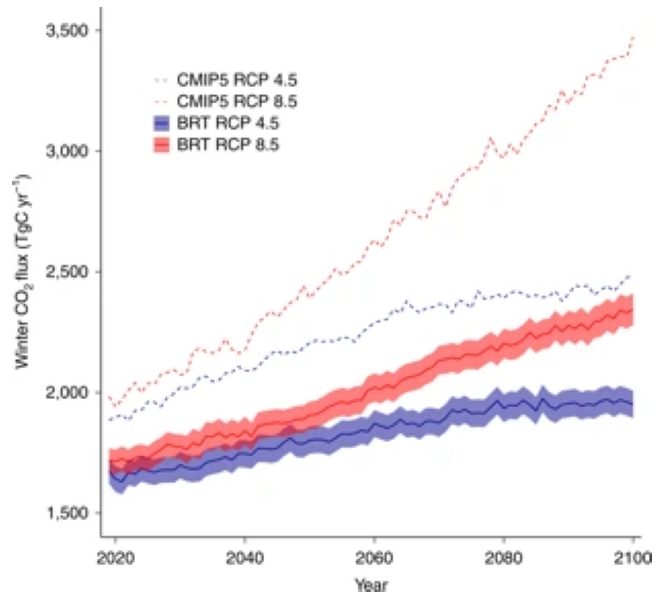

Researchers compiled on-the-ground observations of carbon dioxide emissions across many sites and combined these with remote sensing data and ecosystem models to assess current and future carbon losses during winter for northern permafrost regions. They estimate a yearly loss of 1.7 billion metric tons of carbon from the permafrost region during the winter season from 2003 to 2017 compared to the estimated average of 1 billion metric tons of carbon taken up during the growing season.

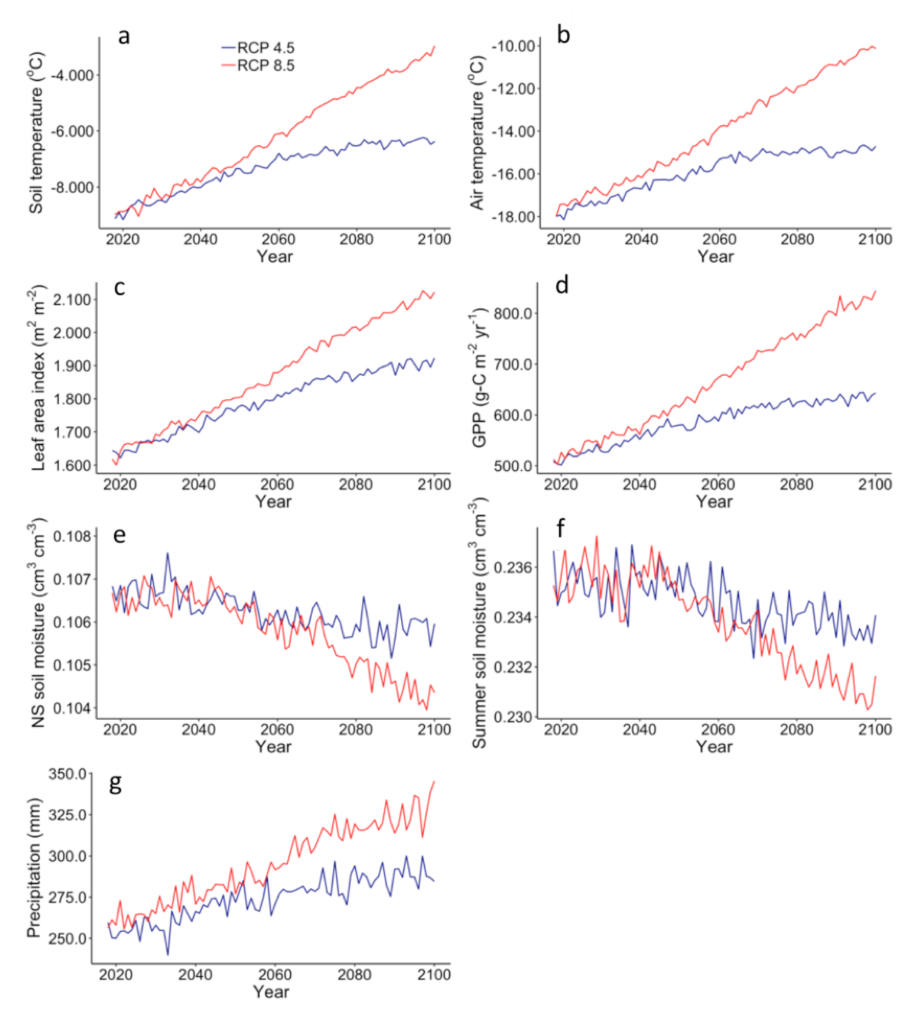

To extend model predictions to warmer conditions in 2100, the climate predicted for different scenarios of future fossil fuel emissions were used to calculate the effect on permafrost. If fossil fuel use is modestly reduced over the next century, winter carbon dioxide emissions would increase 17% compared with current emissions. Under a scenario where fossil fuel use continues to increase at current rates through the middle of the century, winter carbon dioxide emissions from permafrost would rise by 41%.

“The warmer it gets, the more carbon will be released into the atmosphere from the permafrost region, which will add to further warming,” said co-author Brendan Rogers, a climate scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center. “It’s concerning that our study, which used many more observations than ever before, indicates a much stronger Arctic carbon source in the winter. We may be witnessing a transition from an annual Arctic carbon sink to a carbon source, which is not good news.”

Climate modeling teams across the globe are trying to incorporate processes and dynamic events that influence permafrost’s carbon emissions. For example, thermokarst lakes formed by melting ice can speed up the rate of carbon dioxide emissions by exposing deeper layers of permafrost to warmer temperatures. Likewise, Arctic and boreal forest fires, which are becoming more frequent and severe, can remove the insulating top layer of soil, accelerating and deepening permafrost thaw.

“Those interactions are still not accounted for in most of the models and will undoubtedly increase estimates of carbon emissions from permafrost regions,” Rogers said.

Arctic Shifts to a Carbon Source due to Winter Soil Emissions

Large loss of CO2 in winter observed across the northern permafrost region

ABSTRACT: Recent warming in the Arctic, which has been amplified during the winter1,2,3, greatly enhances microbial decomposition of soil organic matter and subsequent release of carbon dioxide (CO2)4. However, the amount of CO2 released in winter is not known and has not been well represented by ecosystem models or empirically based estimates5,6. Here we synthesize regional in situ observations of CO2 flux from Arctic and boreal soils to assess current and future winter carbon losses from the northern permafrost domain. We estimate a contemporary loss of 1,662 TgC per year from the permafrost region during the winter season (October–April). This loss is greater than the average growing season carbon uptake for this region estimated from process models (−1,032 TgC per year). Extending model predictions to warmer conditions up to 2100 indicates that winter CO2 emissions will increase 17% under a moderate mitigation scenario—Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5—and 41% under business-as-usual emissions scenario—Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5. Our results provide a baseline for winter CO2 emissions from northern terrestrial regions and indicate that enhanced soil CO2 loss due to winter warming may offset growing season carbon uptake under future climatic conditions.

Large loss of CO2 in winter observed across the northern permafrost region