Current coal phase-out pledges are insufficient to hit Paris climate goal

27 June 2019 (Chalmers University of Technology) – The Powering Past Coal Alliance, or PPCA, is a coalition of 30 countries and 22 cities and states that aims to phase out unabated coal power. But analysis led by Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, published in Nature Climate Change, shows that members mainly pledge to close older plants near the end of their lifetimes, resulting in limited emissions reductions. The research also shows that expansion of the PPCA to major coal consuming countries would face economic and political difficulties.

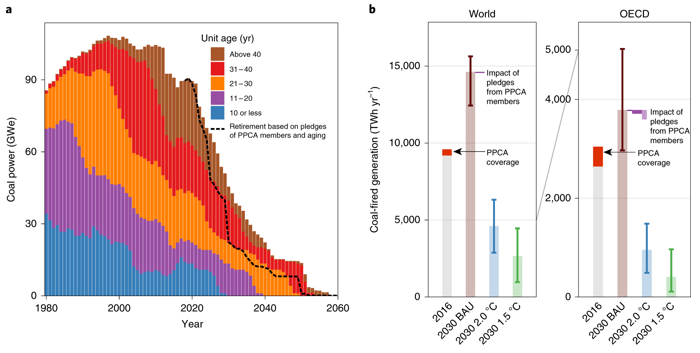

By analysing a worldwide database of coal power plants, the researchers have shown that pledges from PPCA members will result in a reduction of about 1.6 gigatonnes of CO2 from now until 2050. This represents only around 1/150th of projected CO2 emissions over the same time period from all coal power plants which are already operating globally.

“To keep global warming below 1.5°C, as aimed for in the Paris climate agreement, we need to phase-out unabated coal power – that is, when the carbon emissions are not captured – by the middle of this century. The Powering Past Coal Alliance is a good start but so far, only wealthy countries which don’t use much coal, and some countries which don’t use any coal power, have joined,” says Jessica Jewell, Assistant Professor at the Department of Space, Earth and the Environment at Chalmers University of Technology, and lead researcher on the article.

To investigate the likelihood of expanding the PPCA, Jessica Jewell and her colleagues compared its current members with countries which are not part of the Alliance. They found that PPCA members are wealthy nations with small electricity demand growth, older power plants and low coal extraction and use. Most strikingly, these countries invariably rank higher in terms of government openness and transparency, with democratically elected politicians, independence from private interests and strong safeguards against corruption

Not all countries have the resources to make such commitments. It is important to evaluate the costs of and capacities for climate action, to understand the political feasibility of climate targets.

Jessica Jewell, Assistant Professor at the Department of Space, Earth and the Environment at Chalmers University of Technology

These characteristics are dramatically different from major coal users such as China, where electricity demand is rapidly growing, coal power plants are young and responsible for a large share of electricity production, and which ranks lower on government transparency and independence.

The researchers predict therefore, that while countries like Spain, Japan, Germany, and several other smaller European countries may sign up in the near future, countries like China – which alone accounts for about half of all coal power usage worldwide – and India, with expanding electricity sectors and domestic coal mining are unlikely to join the PPCA any time soon.

And recent developments confirm these predictions. Germany recently announced plans to phase out coal power, which could lead to a further reduction of 1.6 gigatonnes of CO2 – a doubling of the PPCA’s reductions. On the other hand, the USA and Australia illustrate the difficulties of managing the coal sector in countries with persistent and powerful mining interests. The recent election in Australia resulted in the victory of a pro-coal candidate, supportive of expanding coal mining and upgrading coal power plants.

More generally, the research suggests that coal phase-out is feasible when it does not incur large-scale losses, such as closing down newly constructed power plants or coal mines. Moreover, countries need the economic and political capacity to withstand these losses. Germany, for instance, has earmarked 40 billion Euros for compensating affected regions.

“Not all countries have the resources to make such commitments. It is important to evaluate the costs of and capacities for climate action, to understand the political feasibility of climate targets,” explains Jessica Jewell.

Current coal phase-out pledges are insufficient

Prospects for powering past coal

ABSTRACT: To keep global warming within 1.5 °C of pre-industrial levels, there needs to be a substantial decline in the use of coal power by 20301,2 and in most scenarios, complete cessation by 20501,3. The members of the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA), launched in 2017 at the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties, are committed to “phasing out existing unabated coal power generation and a moratorium on new coal power generation without operational carbon capture and storage”4. The alliance has been hailed as a ‘political watershed’5 and a new ‘anti-fossil fuel norm’6. Here we estimate that the premature retirement of power plants pledged by PPCA members would cut emissions by 1.6 GtCO2, which is 150 times less than globally committed emissions from existing coal power plants. We also investigated the prospect of major coal consumers joining the PPCA by systematically comparing members to non-members. PPCA members extract and use less coal and have older power plants, but this alone does not fully explain their pledges to phase out coal power. The members of the alliance are also wealthier and have more transparent and independent governments. Thus, what sets them aside from major coal consumers, such as China and India, are both lower costs of coal phase-out and a higher capacity to bear these costs.