Adjusting carbon emissions to the Paris climate commitments would prevent thousands of heat-related deaths per city – “Compelling evidence for the heat-related health benefits of limiting global warming to 1.5°C”

5 June 2019 (University of Bristol) – Thousands of annual heat-related deaths could be potentially avoided in major US cities if global temperatures are limited to the Paris Climate Goals compared with current climate commitments, a new study led by the University of Bristol has found.

The research, published today in the journal Science Advances, is highly relevant to decisions about strengthening national climate actions in 2020, when the next round of climate pledges is due in 2020.

The Paris Agreement aims at keeping global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with an ambition of limiting warming to 1.5°C. Nations in the agreement are required to submit their climate pledges every five years.

Climate scientists and epidemiologists from the UK and the US combined observed temperature and mortality data with climate projections of different warmer worlds, to estimate changes in the number of heat-related deaths for 15 major US cities.

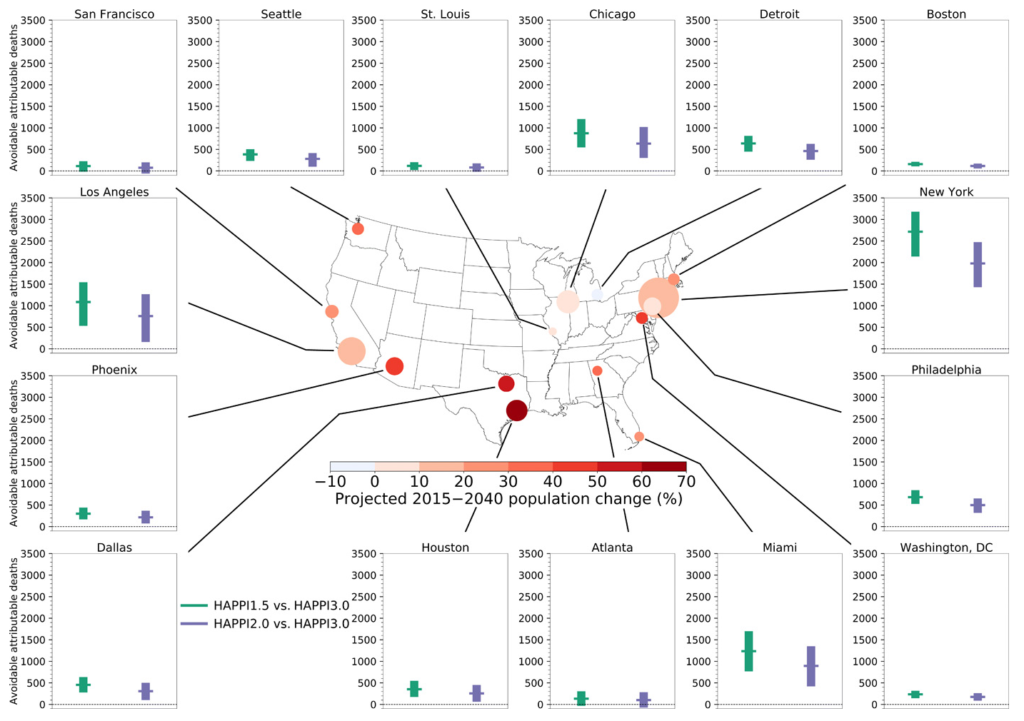

Their findings showed that limiting warming to the lower Paris Climate Goal could avoid 110 to 2,720 annual heat-related deaths during extreme heat-events, depending on the city.

This is substantially more beneficial than limiting warming to the upper Paris Climate Goal, which could avoid 70 to 1,980 deaths per city.

Our study brings together a wide range of physical and social complexities to show just how human lives could be impacted if we do not cut carbon emissions. Considering the US citizens that will be adversely affected by increasing global temperatures, we strongly encourage them to hold their politicians to account.

Professor Dann Mitchell, University of Bristol

Lead author, Dr Eunice Lo from the University of Bristol’s Cabot Institute, said: “If global temperature rise is reduced to 1.5°C from where we are headed, the cities’ exposure to extreme heat would decrease and up to thousands of annual heat-related deaths could be avoided per city.

“Strengthened climate actions are needed as they would substantially benefit public health in the United States.”

Co-lead author, Professor Dann Mitchell, also from the University of Bristol’s Cabot Institute, added: “We are no longer counting the impact of climate in change in terms of degrees of global warming, but rather in terms of number of lives lost.

“Our study brings together a wide range of physical and social complexities to show just how human lives could be impacted if we do not cut carbon emissions. Considering the US citizens that will be adversely affected by increasing global temperatures, we strongly encourage them to hold their politicians to account.”

The Trump administration announced US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in 2017. However, the effective withdrawal date is not until 2020, and states including New York and California are still committed to achieving the US climate goal within the agreement.

Professor Kristie Ebi, US-based public health expert and co-author of the study from the University of Washington, said: “Municipal adaptation strategies including increases in passive cooling and awareness of heat-related health risks play an important role in increasing resilience to future higher temperatures.”

Recognising the dangerous consequences of climate change through the work of climate experts at the University and from around the globe, the University of Bristol became the first UK university to declare a climate emergency in April 2019.

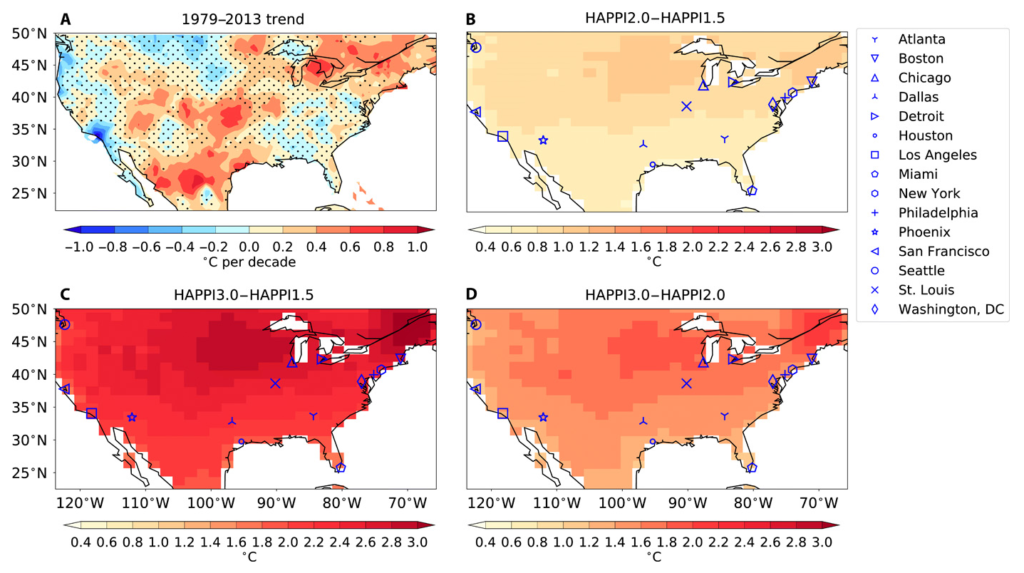

ABSTRACT: Current greenhouse gas mitigation ambition is consistent with ~3°C global mean warming above preindustrial levels. There is a clear need to strengthen mitigation ambition to stabilize the climate at the Paris Agreement goal of warming of less than 2°C. We specify the differences in city-level heat-related mortality between the 3°C trajectory and warming of 2° and 1.5°C. Focusing on 15 U.S. cities where reliable climate and health data are available, we show that ratcheting up mitigation ambition to achieve the 2°C threshold could avoid between 70 and 1980 annual heat-related deaths per city during extreme events (30-year return period). Achieving the 1.5°C threshold could avoid between 110 and 2720 annual heat-related deaths. Population changes and adaptation investments would alter these numbers. Our results provide compelling evidence for the heat-related health benefits of limiting global warming to 1.5°C in the United States.