Russia’s war on Ukraine dims global economic outlook as inflation accelerates – Africa faces new shock as war raises food and fuel costs – “This crisis unfolds even as the global economy has not yet fully recovered from the pandemic”

By Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas

19 April 2022

(IMF) – Global economic prospects have been severely set back, largely because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

This crisis unfolds even as the global economy has not yet fully recovered from the pandemic. Even before the war, inflation in many countries had been rising due to supply-demand imbalances and policy support during the pandemic, prompting a tightening of monetary policy. The latest lockdowns in China could cause new bottlenecks in global supply chains.

In this context, beyond its immediate and tragic humanitarian impact, the war will slow economic growth and increase inflation. Overall economic risks have risen sharply, and policy tradeoffs have become even more challenging.

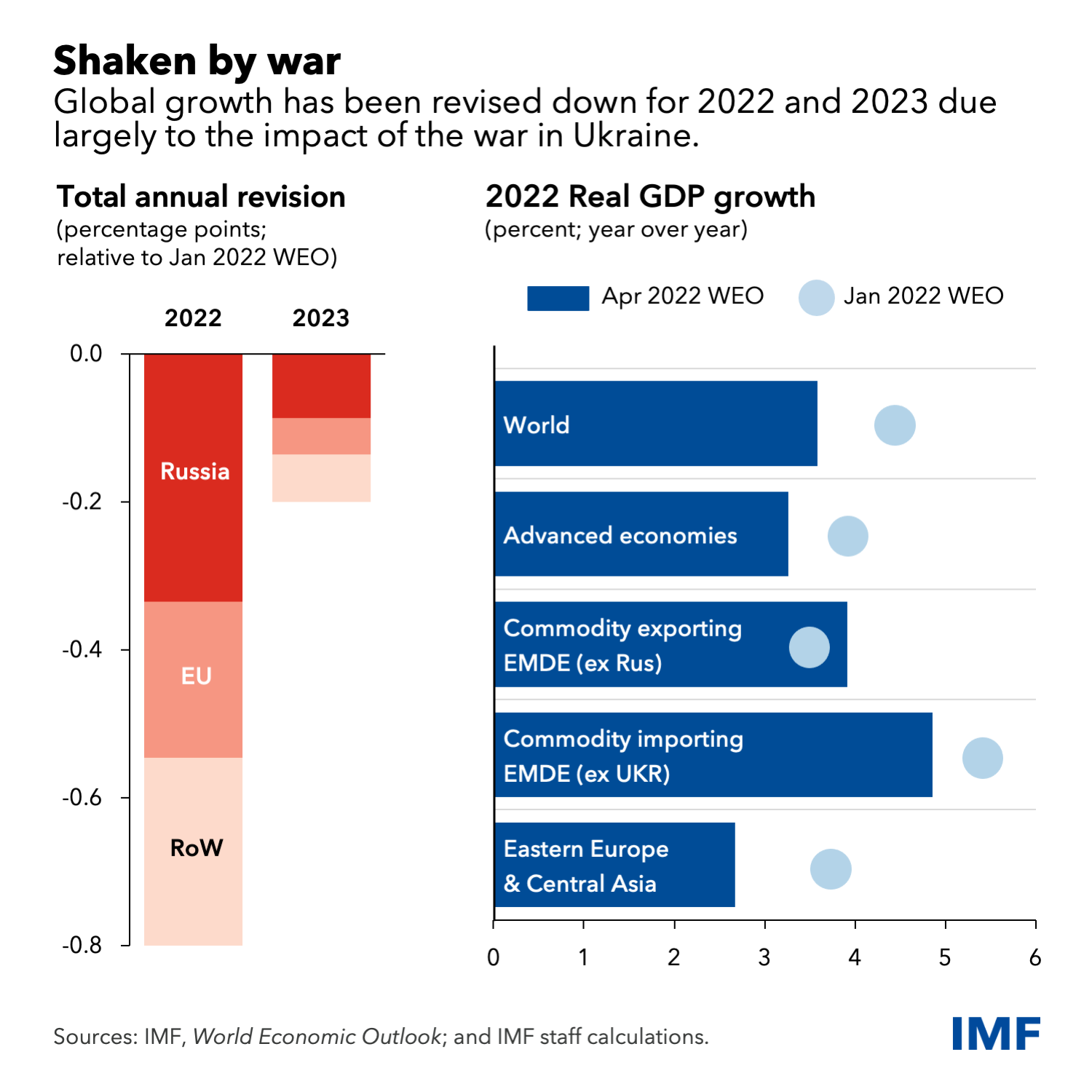

Compared to our January forecast, we have revised our projection for global growth downwards to 3.6 percent in both 2022 and 2023. This reflects the direct impact of the war on Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, with both countries projected to experience steep contractions. This year’s growth outlook for the European Union has been revised downward by 1.1 percentage points due to the indirect effects of the war, making it the second largest contributor to the overall downward revision.

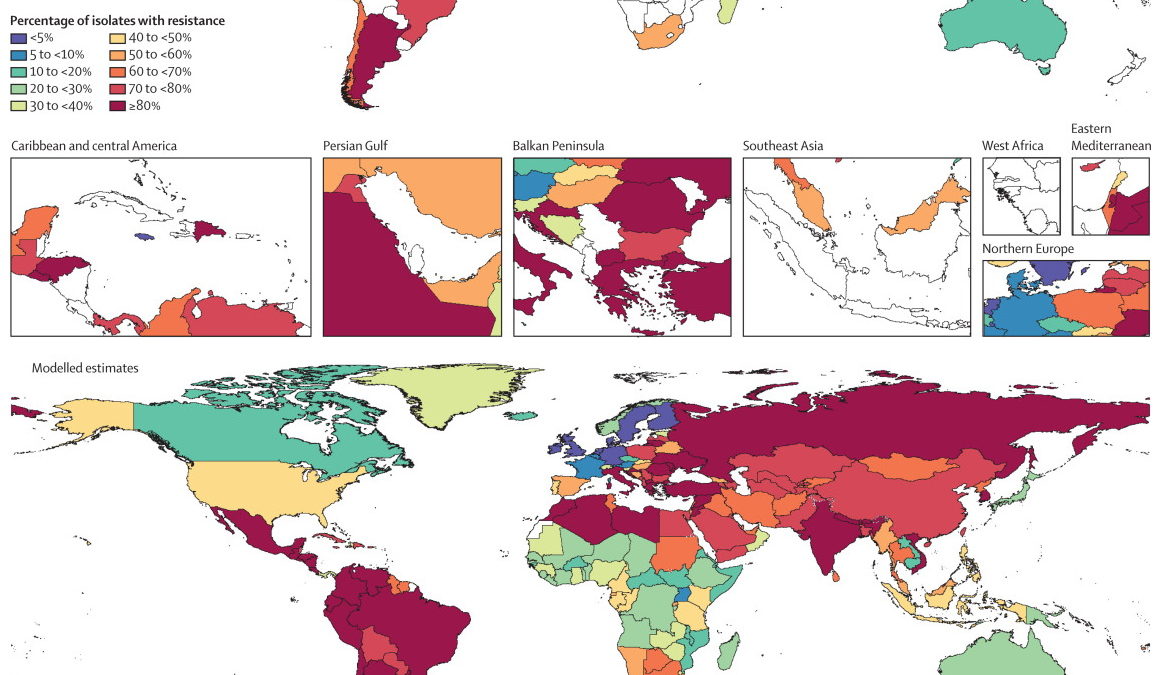

The war adds to the series of supply shocks that have struck the global economy in recent years. Like seismic waves, its effects will propagate far and wide—through commodity markets, trade, and financial linkages. Russia is a major supplier of oil, gas, and metals, and, together with Ukraine, of wheat and corn. Reduced supplies of these commodities have driven their prices up sharply. Commodity importers in Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa are most affected. But the surge in food and fuel prices will hurt lower-income households globally, including in the Americas and the rest of Asia.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia have large direct trade and remittance links with Russia and are expected to suffer. The displacement of about 5 million Ukrainian people to neighboring countries, especially Poland, Romania, Moldova, and Hungary, adds to economic pressures in the region.

Pressures amplified

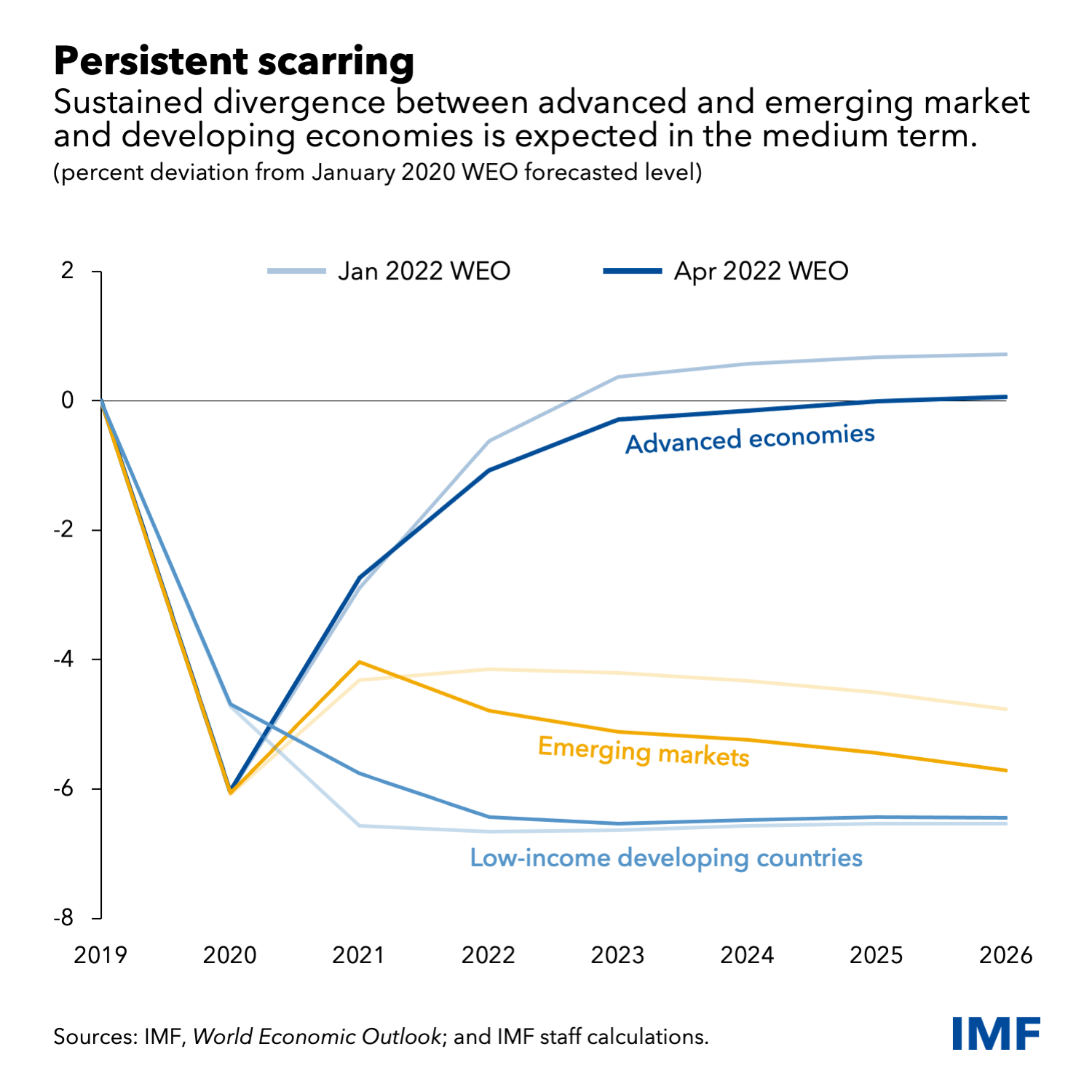

The medium-term outlook is revised downwards for all groups, except commodity exporters who benefit from the surge in energy and food prices. Aggregate output for advanced economies will take longer to recover to its pre-pandemic trend. And the divergence that opened up in 2021 between advanced and emerging market and developing economies is expected to persist, suggesting some permanent scarring from the pandemic.

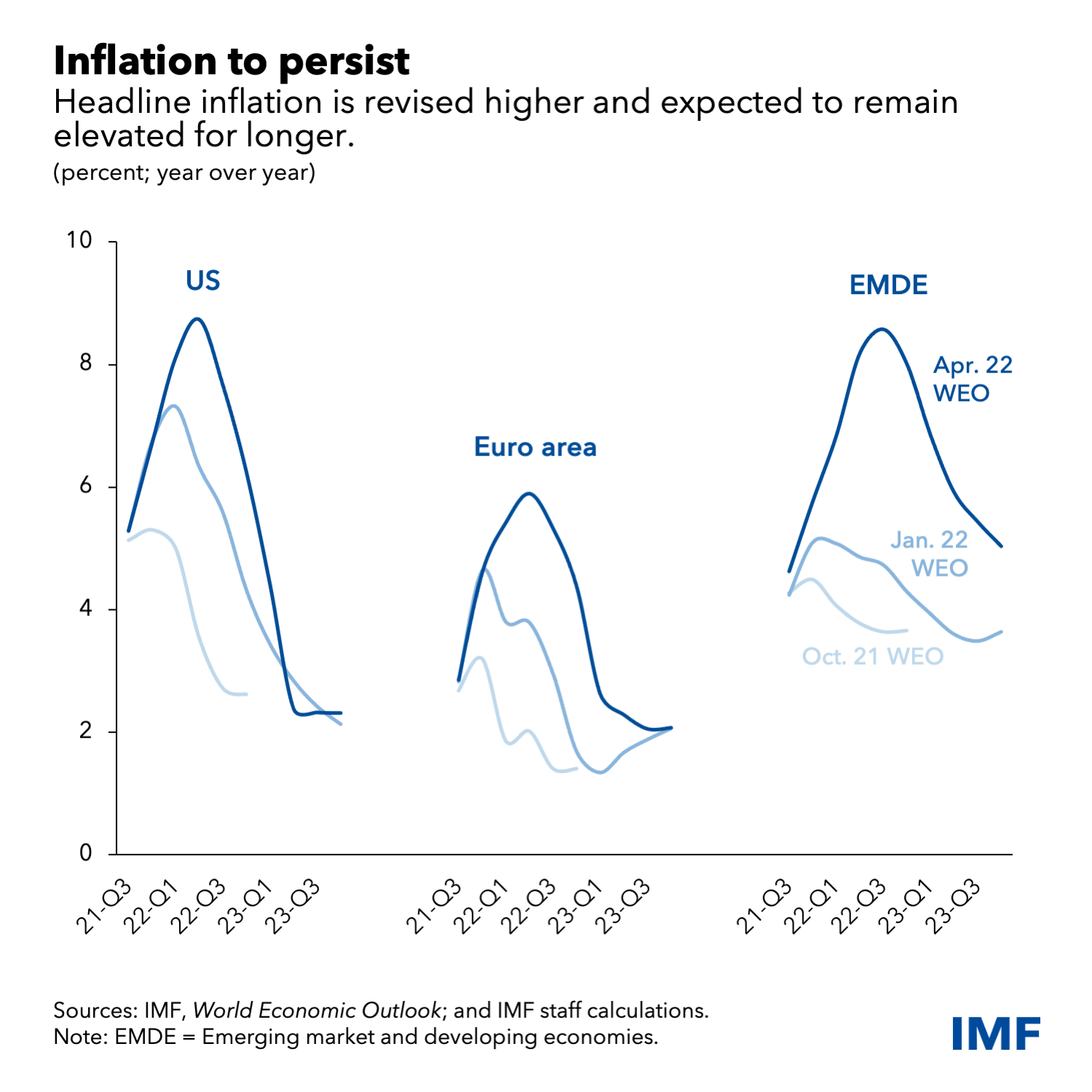

Inflation has become a clear and present danger for many countries. Even prior to the war, it surged on the back of soaring commodity prices and supply-demand imbalances. Many central banks, such as the Federal Reserve, had already moved toward tightening monetary policy. War-related disruptions amplify those pressures. We now project inflation will remain elevated for much longer. In the United States and some European countries, it has reached its highest level in more than 40 years, in the context of tight labor markets.

The risk is rising that inflation expectations drift away from central bank inflation targets, prompting a more aggressive tightening response from policymakers. Furthermore, increases in food and fuel prices may also significantly increase the prospect of social unrest in poorer countries.

Immediately after the invasion, financial conditions tightened for emerging markets and developing countries. So far, this repricing has been mostly orderly. Yet, several financial fragility risks remain, raising the prospect of a sharp tightening of global financial conditions as well as capital outflows.

On the fiscal side, policy space was already eroded in many countries by the pandemic. Withdrawal of extraordinary fiscal support was projected to continue. The surge in commodity prices and the increase in global interest rates will further reduce fiscal space, especially for oil- and food-importing emerging markets and developing economies.

The war also increases the risk of a more permanent fragmentation of the world economy into geopolitical blocks with distinct technology standards, cross-border payment systems, and reserve currencies. Such a tectonic shift would cause long-run efficiency losses, increase volatility and represent a major challenge to the rules-based framework that has governed international and economic relations for the last 75 years. [more]

War Dims Global Economic Outlook as Inflation Accelerates

Africa Faces New Shock as War Raises Food and Fuel Costs

By Abebe Aemro Selassie and Peter Kovacs

28 April 2022

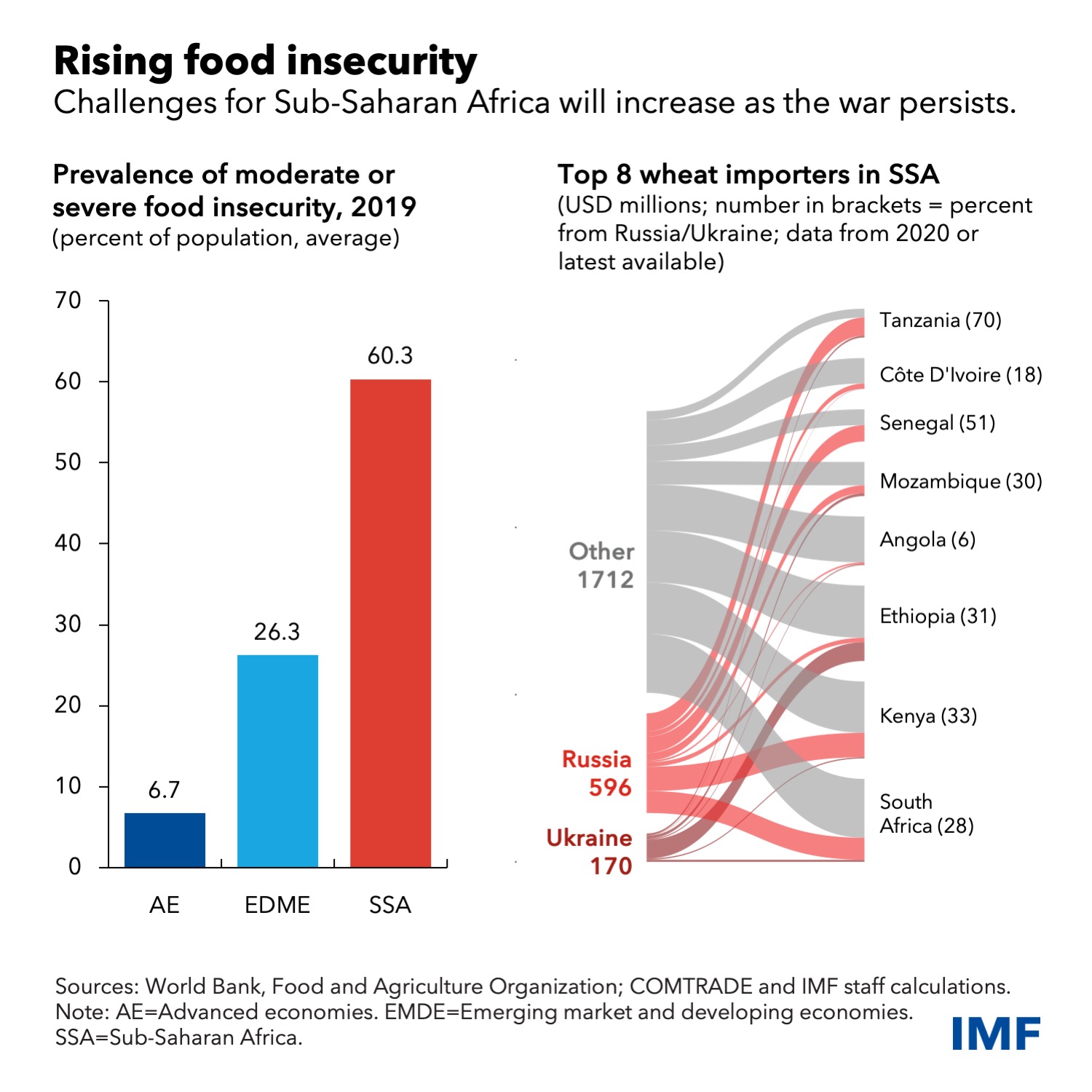

(IMF) – Sub-Saharan African countries find themselves facing another severe and exogenous shock. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted a surge in food and fuel prices that threatens the region’s economic outlook. This latest setback could not have come at a worse time—as growth was starting to recover and policymakers were beginning to address the social and economic legacy of COVID-19 pandemic and other development challenges. The effects of the war will be deeply consequential, eroding standards of living and aggravating macroeconomic imbalances.

We now expect growth to slow to 3.8 percent this year from last year’s better-than-expected 4.5 percent, according to our latest Regional Economic Outlook. Though we project annual growth to average 4 percent over the medium term, it will be too slow to make up for ground lost to the pandemic. Inflation in the region is expected to remain elevated in 2022 and 2023 at 12.2 percent and 9.6 percent respectively—the first time since 2008 that regional average inflation will reach such high levels.

There are three main channels through which the war is impacting countries—with notable differentiation both across and within countries:

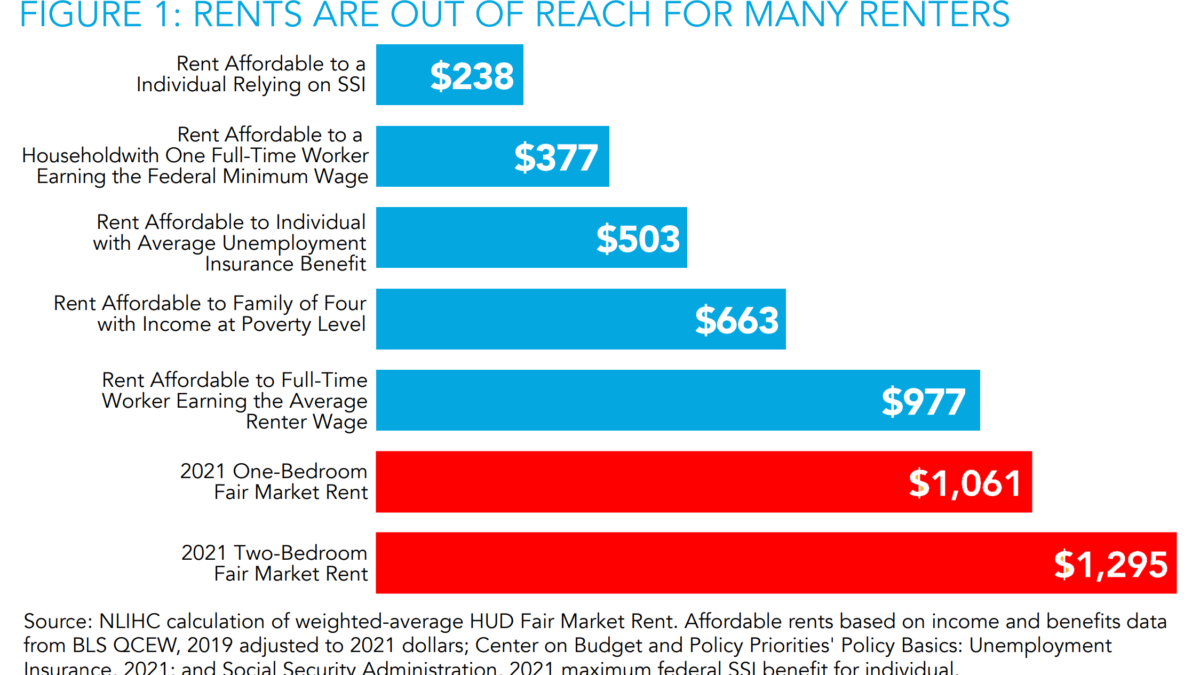

- Prices for food, which accounts for about 40 percent of consumer spending in the region, are rising rapidly. Around 85 percent of the region’s wheat supplies are imported. Higher fuel and fertilizer prices also affect domestic food production. Together, these factors will disproportionately hurt the poor, especially in urban areas, and will increase food insecurity.

- Higher oil prices will boost the import bill for the region’s oil importers by about $19 billion, worsening trade imbalances and raising transport and other consumer costs. Oil-importing fragile states will be hit hardest, with fiscal balances expected to deteriorate by around 0.8 percent of gross domestic product compared to the October 2021 forecast—twice that of other oil-importing countries. The region’s eight petroleum exporters, however, benefit from higher crude prices.

- The shock is set to make an already delicate fiscal balancing act more difficult: increasing development spending, mobilizing more tax revenues, and containing debt pressures. Fiscal authorities generally aren’t well-positioned for additional shocks after the pandemic. Half of the region’s low-income countries are already in or at high risk of distress. Rising oil prices also represent a direct fiscal cost for countries through fuel subsidies, while inflation will make reducing these subsidies unpopular. Spending pressures will only increase as growth slows, while rising interest rates in advanced economies may make financing more costly and harder to obtain for some governments.

Countries need a careful policy response to address these daunting challenges. Fiscal policy will need to be targeted to avoid adding to debt vulnerabilities. Policymakers should as much as possible use direct transfers to protect the most vulnerable households. Improving access to finance for farmers and small businesses would also help.

Countries that can’t provide targeted transfers can use temporary subsidies or targeted tax reductions, with clear end dates. If well-designed, they can protect households by providing time to adjust to international prices more gradually. To enhance resilience to future crises, it remains important for these countries to develop effective social safety nets. Digital technology, such as mobile money or smart cards, could be used to better target social transfers, as Togo did during the pandemic.

Net commodity-importers, such as Benin, Ethiopia and Malawi, will need to find resources to protect the vulnerable by reprioritizing spending. Net exporters, like Nigeria, are likely to benefit from rising oil prices, but a fiscal gain is only possible if the fuel subsidies they provide are contained. It is important that windfalls are largely directed to strengthen policy buffers, supported by strong fiscal institutions such as a credible medium-term fiscal framework and a strong public financial management system.

To navigate the trade-off between curbing inflation and supporting growth, central banks will need to monitor price developments carefully and raise interest rates if inflation expectations drift up. They must also guard against the financial stability risks posed by higher rates and maintain a credible policy framework underpinned by strong independence and clear communication. [more]