Facing unbearable heat, Qatar has begun to air-condition the outdoors – “The Persian Gulf is a prophecy of what’s to come”

By Steven Mufson

16 October 2019

DOHA, Qatar (The Washington Post) – It was 116 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade outside the new Al Janoub soccer stadium, and the air felt to air-conditioning expert Saud Ghani as if God had pointed “a giant hair dryer” at Qatar.

Yet inside the open-air stadium, a cool breeze was blowing. Beneath each of the 40,000 seats, small grates adorned with Arabic-style patterns were pushing out cool air at ankle level. And since cool air sinks, waves of it rolled gently down to the grassy playing field. Vents the size of soccer balls fed more cold air onto the field.

Ghani, an engineering professor at Qatar University, designed the system at Al Janoub, one of eight stadiums that the tiny but fabulously rich Qatar must get in shape for the 2022 World Cup. His breakthrough realization was that he had to cool only people, not the upper reaches of the stadium — a graceful structure designed by the famed Zaha Hadid Architects and inspired by traditional boats known as dhows.

“I don’t need to cool the birds,” Ghani said.

Qatar, the world’s leading exporter of liquefied natural gas, may be able to cool its stadiums, but it cannot cool the entire country. Fears that the hundreds of thousands of soccer fans might wilt or even die while shuttling between stadiums and metros and hotels in the unforgiving summer heat prompted the decision to delay the World Cup by five months. It is now scheduled for November, during Qatar’s milder winter.

The change in the World Cup date is a symptom of a larger problem — climate change.

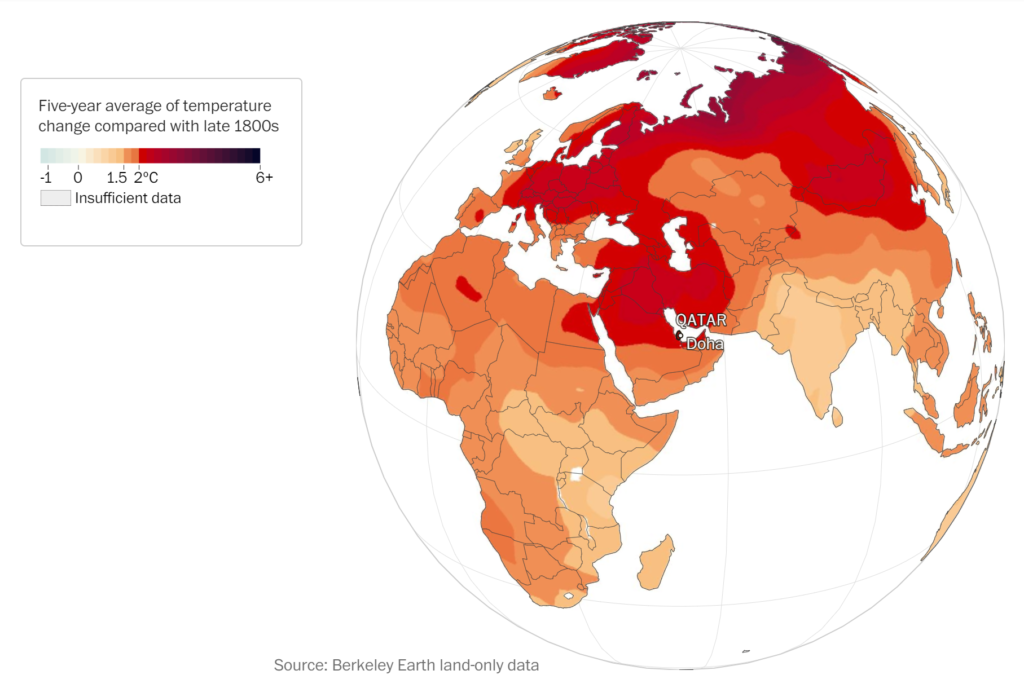

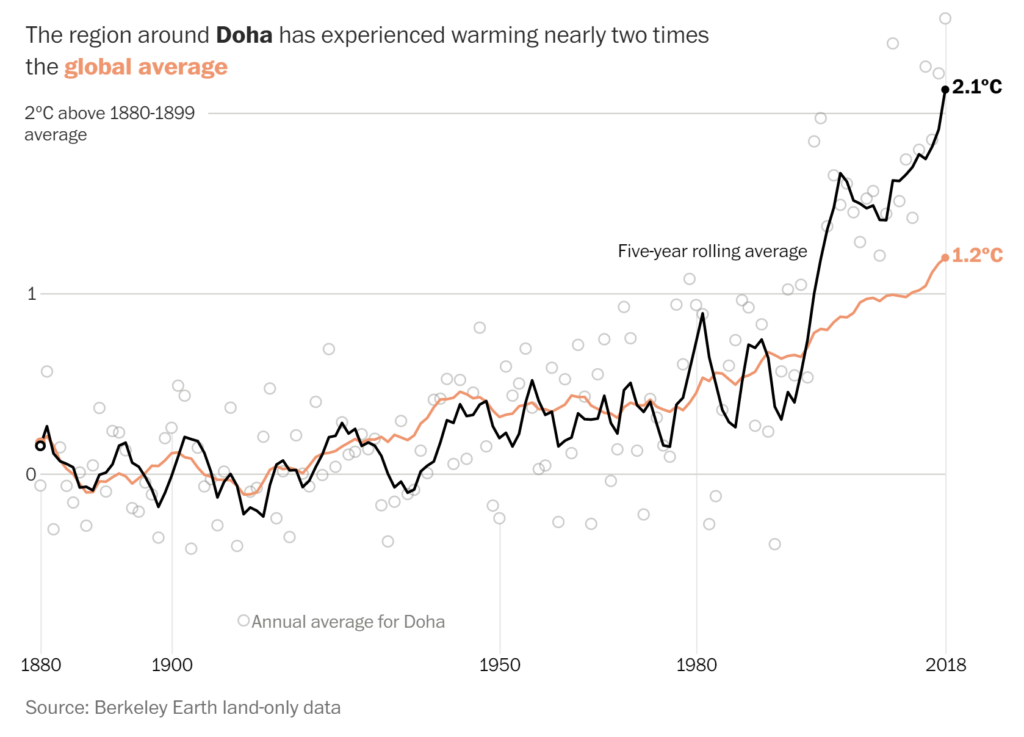

Already one of the hottest places on Earth, Qatar has seen average temperatures rise more than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial times, the current international goal for limiting the damage of global warming. The 2015 Paris climate summit said it would be better to keep temperatures “well below” that, ideally to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. […]

“Qatar is one of the fastest warming areas of the world, at least outside of the Arctic,” said Zeke Hausfather, a climate data scientist at Berkeley Earth, a nonprofit temperature analysis group. “Changes there can help give us a sense of what the rest of the world can expect if we do not take action to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions.” […]

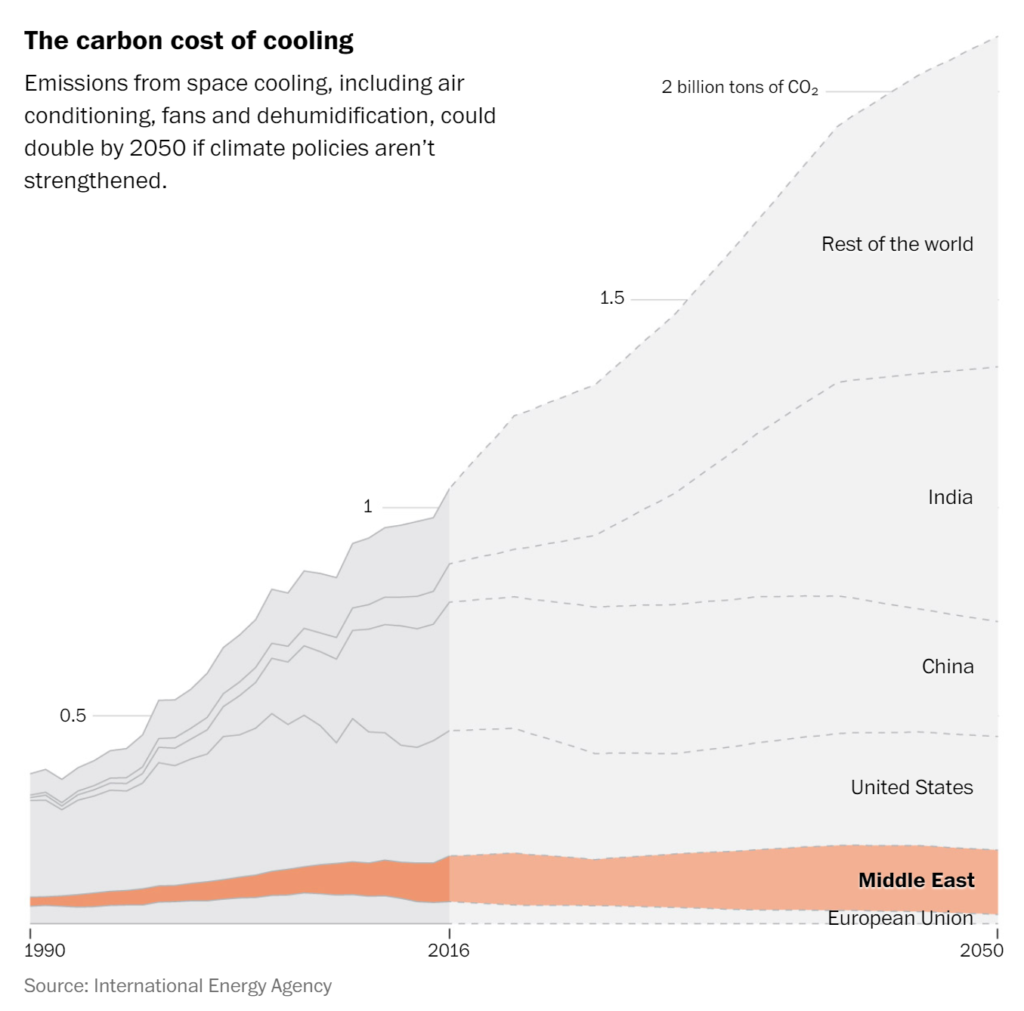

To survive the summer heat, Qatar not only air-conditions its soccer stadiums, but also the outdoors — in markets, along sidewalks, even at outdoor malls so people can window shop with a cool breeze. “If you turn off air conditioners, it will be unbearable. You cannot function effectively,” says Yousef al-Horr, founder of the Gulf Organization for Research and Development. […]

The danger is acute in Qatar because of the Persian Gulf humidity. The human body cools off when its sweat evaporates. But when humidity is very high, evaporation slows or stops. “If it’s hot and humid and the relative humidity is close to 100 percent, you can die from the heat you produce yourself,” said Jos Lelieveld, an atmospheric chemist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany who is an expert on Middle East climate.

That became abundantly clear in late September, as Doha hosted the 2019 World Athletics Championships. It moved the start time for the women’s marathon to midnight Sept. 28. Water stations handed out sponges dipped in ice-cold water. First-aid responders outnumbered the contestants. But temperatures hovered around 90 degrees Fahrenheit and 28 of the 68 starters failed to finish, some taken off in wheelchairs. […]

“With the coming global environmental collapse, to live completely indoors is like, the only way we’ll be able to survive. The Gulf’s a prophecy of what’s to come,” said Qatari American artist Sophia al-Maria in an interview in Dazed Digital, an online magazine covering fashion and culture. [more]

Facing unbearable heat, Qatar has begun to air-condition the outdoors