Fires still being set in blazing Bolivia – Up to 18 million wild animals killed, including 500 rare jaguars – “Bolivia needs to rethink its agricultural strategy, as the future of its immeasurable biodiversity is at stake”

By Claire Wordley

1 October 2019

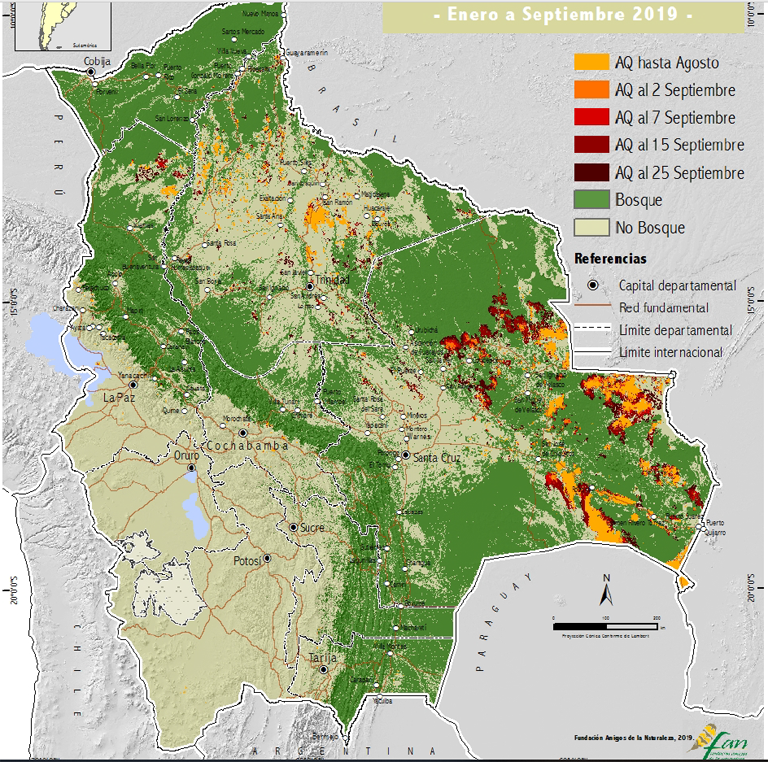

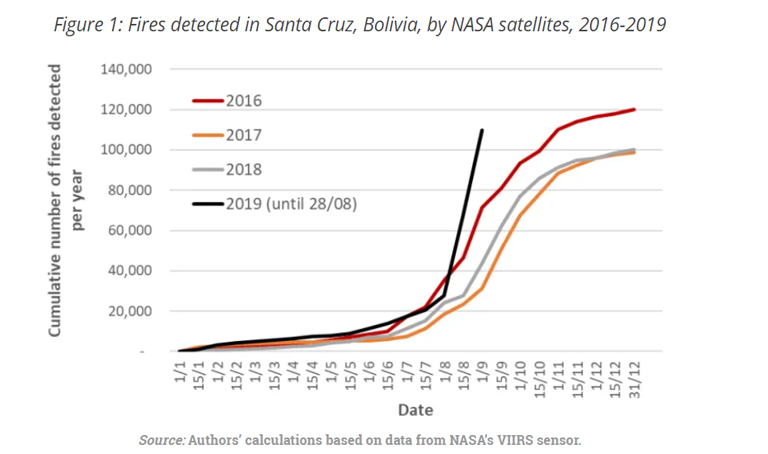

(Mongabay) – Despite over six weeks of firefighting, the infernos destroying Bolivia’s forests continue to spread. 5.3 million hectares (about 13.1 million acres) — an area larger than the whole of Costa Rica — have been destroyed, and about 40 percent of that area was forest. A perfect storm of factors — from an unusually dry year, probably linked to climate change, to a new law allowing burning of forest lands — have combined to make this one of the worst years this century for forest fires in the megadiverse nation.

But are these fires out of the ordinary?

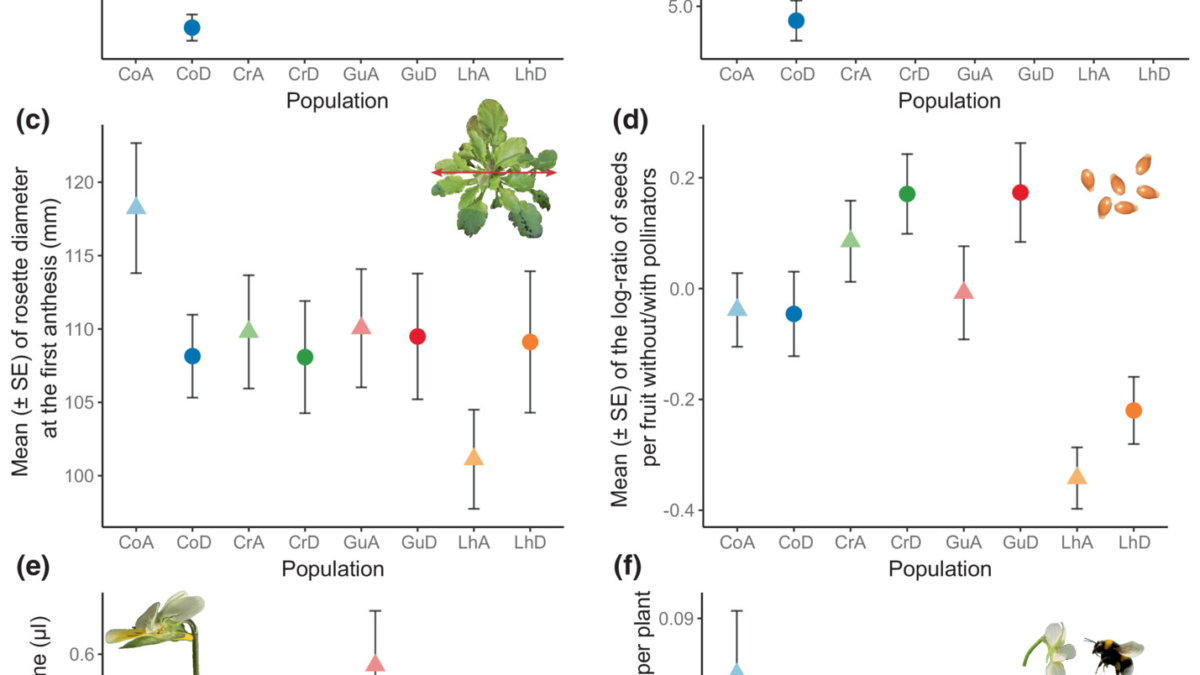

Fires are set every year in Bolivia, usually to clear land for agriculture. But Assistant Professor Carwil Bjork-James of Vanderbilt University says that the fires this year are especially severe: “We are seeing a dramatic year in terms of the numbers of fires blazing in Bolivia, and the acreage consumed by them. If the fires continue at their current pace, it will be the second worst year of the twenty-first century.”

The number of fires set this year in the worst-affected Santa Cruz district of Bolivia — which had the dubious distinction of being the number one deforestation hotspot in the Amazon even before the current fires — is well above that of previous years. Over 83,000 fires were set in Santa Cruz in August, more than double the number set in 2016, another bad year for fires. There were also differences in where the fires were set, with more than twice as many fires set in remote areas compared to 2016.

Why are fires being set?

Many are pointing the finger at Supreme Decree 3973, announced in July, which legalized burning forest areas. Less than a month after the decree was issued, out-of-control fires were reported. This decree, along with Law 741, which allows up to 20 hectares of land to be burned at a time, have been denounced by major Indigenous organizations, the Catholic Church of Bolivia, Amnesty International, and at least 21 civil society groups.

These laws appear to be aimed at fulfilling government pledges to triple agricultural area and export beef to China. Bolivia’s agricultural industry has defended the legalization of burning, asking President Evo Morales not to “kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.” Morales has “paused” the laws until the current fires are under control — but on-the-ground reports suggest that there are no attempts at enforcement.

While many Bolivians are fighting the fires, some are still setting them. An ecologist working with firefighters told me that “people who for whatever reason want to burn the forest are now taking advantage of the situation to do so, knowing that the authorities either can’t or won’t implement sanctions. Many of them may also be hoping that there will be a “perdonazo” (a general pardon) at some point in the future, which will allow them to keep hold of land that has illegally been cleared. Based on what has happened in the past, that’s a fairly safe bet.” […]

Biologists have estimated that 4,000 plant species and 1,600 animal species are affected by the fires. Estimates vary hugely, but between 2 million and 18 million wild animals have been killed, including about 500 rare jaguars.

Indigenous peoples

Assistant Professor Bjork-James, who has worked on social movements and Indigenous rights in Bolivia since 2008, told me that “the fires are the leading edge of the process of converting forested lands into soy plantations, cattle ranches, and small-scale agricultural settlements. In many areas, these new uses run counter to the resource model used by existing Indigenous inhabitants.”

He points to some of the worst affected Indigenous territories — 34 percent of Ñembi Guasu, which hosts the only Indigenous group living in voluntary isolation in Bolivia, has burned, along with 56 percent of Santa Teresita, another Indigenous territory. “As a result, Indigenous people affiliated with CIDOB (Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia), OICH (Chiquitana Indigenous Organization), COICA (Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin), and other Indigenous organizations began a march this week.”

The march is traveling 470 kilometers (292 miles) to the capital of the Santa Cruz district. The marchers demand that the government declare a National Disaster and annul the laws which allow burning. “If we are not heard, we will continue the march to La Paz. We are the people affected by the burning of our big house. We are in mourning for our big house,” said The First Great Chief of the Chiquitan Nation, Beatriz Tapanaché. […]

Biologist Alfredo Romero-Muñoz says that this enormous ecological disaster should trigger policy changes: “The government should repeal the laws that promote deforestation and forest burning for agricultural expansion. Overall, Bolivia needs to rethink its agricultural strategy, as the future of its immeasurable biodiversity is at stake. The forests provide water and resilience to climate change, to which Bolivia is one of the most vulnerable countries.” [more]