We bought everything needed to make $3 million worth of fentanyl. All it took was $3,600 and a web browser.

By Maurice Tamman, Laura Gottesdiener, and Stephen Eisenhammer

25 July 2024

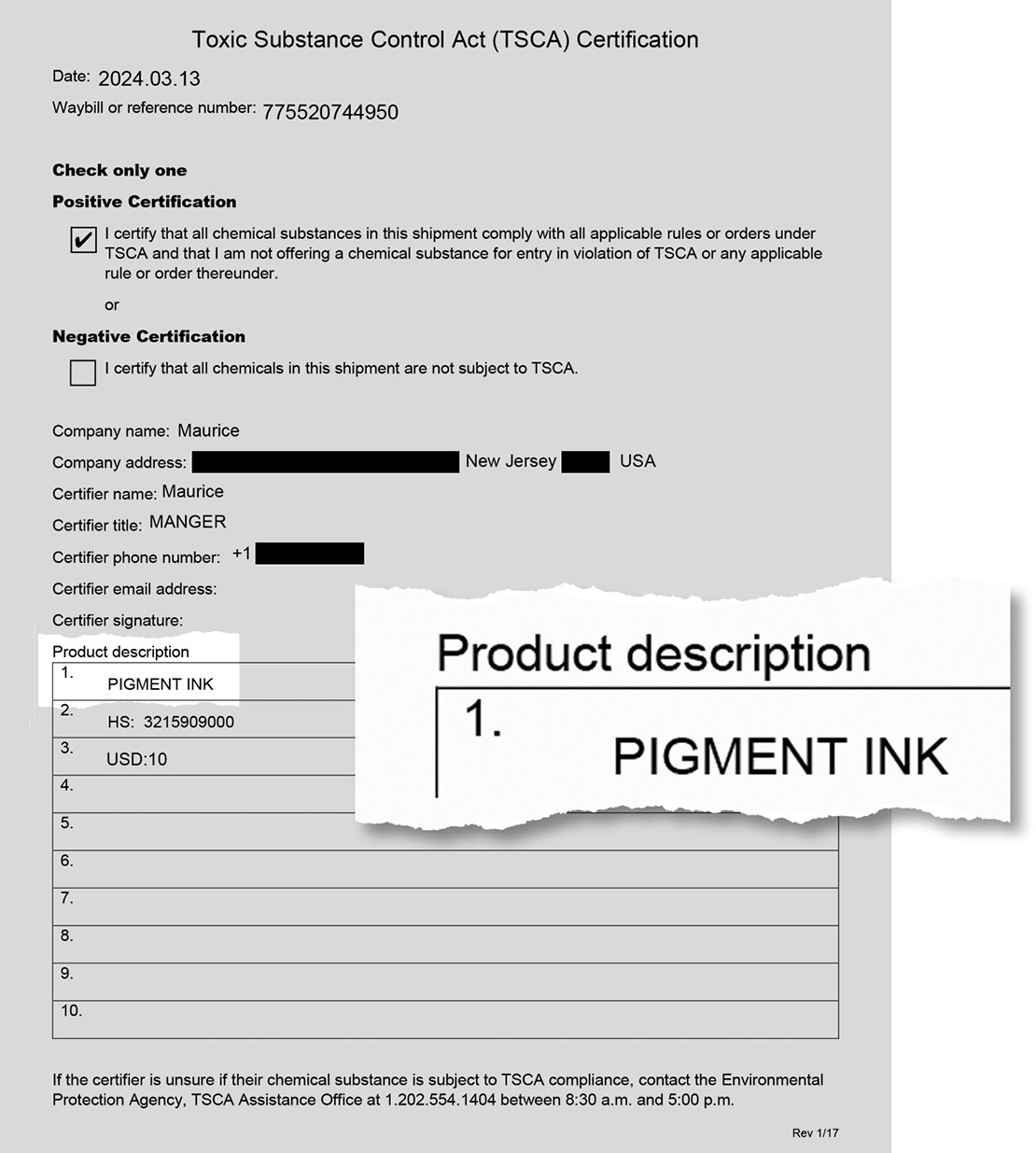

(Reuters) – A cardboard box half the size of a loaf of bread bore a shipping label declaring its contents: “Adapter.” It was delivered in October to a Reuters reporter in Mexico City.

There was no adapter inside that package. Instead, sealed in a metallic Mylar bag was a plastic jar containing a kilogram of 1-boc-4-piperidone, a pale powder that’s a core ingredient of fentanyl. It was enough to produce 750,000 tablets of the deadly drug.

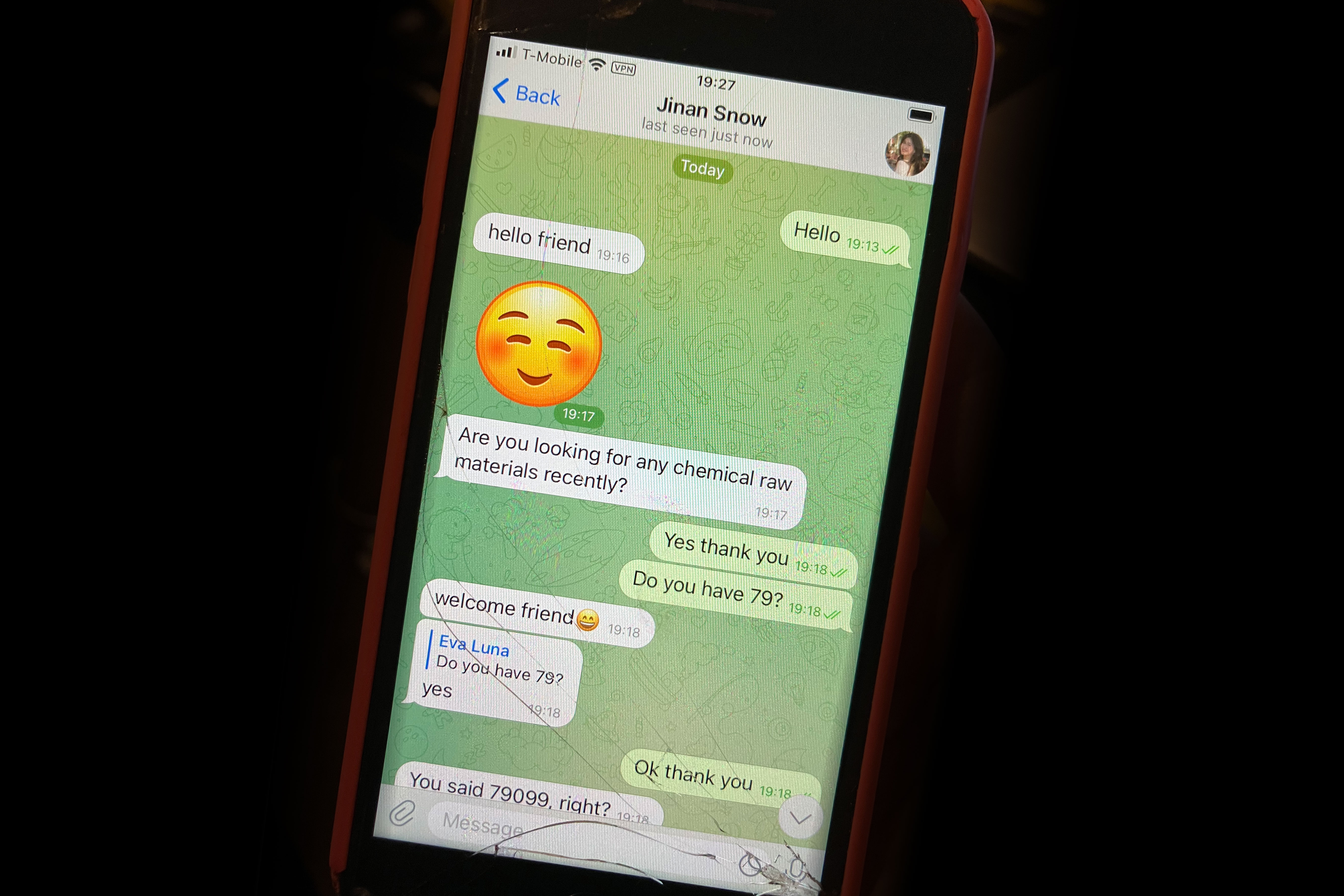

A Reuters reporter had ordered the chemical six weeks earlier from a seller in China. The sales assistant, “Jenny,” used a photo of a Chinese actress as her screen avatar. The price was $440, payable in Bitcoin, delivery by air freight included.

“We can ship safely to Mexico,” Jenny had written in Spanish on the encrypted message platform Telegram in July 2023, when the reporter first inquired about the chemical. “No one knows what we ship.”

Transactions like this are part of the biggest upheaval in the global narcotics trade since the war on drugs began half a century ago. The manufacturing of fentanyl, the synthetic opioid that’s killing tens of thousands of Americans a year, has become an endlessly inventive and ruthlessly efficient global industry.

The trade hinges on chemicals known as “precursors,” which are the drug’s essential ingredients. Compounds called piperidines are the core of fentanyl’s structure. Other precursors provide the remaining building blocks. Combined through chemical reactions, these precursors create a drug 50 times stronger than heroin.

The problem for regulators: Many of the same chemicals used to make fentanyl are also crucial to legitimate industries, from perfumes and pharmaceuticals to rubber and dyes. Tightly restricting all of them would upend global commerce. And because of fentanyl’s potency, even small quantities of these precursors can produce vast numbers of tiny pills using a simple manufacturing process – rendering the ingredients, the final product and the supply chain easy to conceal from authorities.

Anyone with a mailbox, an internet connection and digital currency to pay the tab can source these chemicals, a Reuters investigation found.

Turning these precursors into fentanyl would have required just modest lab skills and a basic grasp of chemistry. One Mexican fentanyl cook who dropped out of school at age 12 told Reuters he learned the trade as an apprentice at an illegal lab.

“It’s like making chicken soup,” said the cook, an independent producer based in the cartel stronghold of Sinaloa state. “It’s mega-easy making that drug.”

The Reuters reporters didn’t make fentanyl, had no intention to do so, and arranged for safe destruction of the chemicals and other materials they purchased. They also followed the guidance of lawyers before making the buys in an effort to ensure they complied with the law. Reuters is withholding detailed instructions and other information that could aid in synthesizing the drug.

The dominant players in the illicit opioid trade – the Mexican cartels that manufacture most of the drugs and smuggle them into America– have been the subject of detailed reporting over the years. Now, as the first news organization to buy and test fentanyl’s essential ingredients, Reuters has penetrated the hidden sub-industry that makes the cartel operations possible: the international supply chain of precursor chemicals.

The fentanyl business is largely a three-nation trading system, with the United States, Mexico and China linked in a toxic triangle as the illicit drug’s biggest consumer, manufacturer and raw-materials supplier. The Reuters investigation has uncovered the names of Chinese sellers, the methods they use to ship their chemicals to North America, and how these packages evade customs inspections in Mexico and the United States. The ease with which the reporters bought the drug-making chemicals and gear exposes holes in the world regulatory framework, and shows how law enforcement is playing catch-up amid a profound transformation of the opioid market.

At the tap of a buyer’s smartphone, Chinese sellers will air-ship fentanyl precursors, sometimes falsely labeled as gadgets, cosmetics and other mundane goods. These packages are loaded onto planes stuffed with nearly identical-looking boxes of cheap exports that leave China by the billions every year.

Major destinations are airports in Mexico and the United States, where the precursor-filled packages typically sail through customs with other merchandise, authorities in both countries said. There’s no need to ship bulky barrels of chemicals and navigate the tricky logistics of getting them onshore, as is the case for drugs like methamphetamine.

“The game is different now,” said Christopher Landberg, deputy assistant secretary in the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. The supply chain is “more difficult to track, it’s more difficult to go after,” and fentanyl itself is “so much more deadly,” he said.

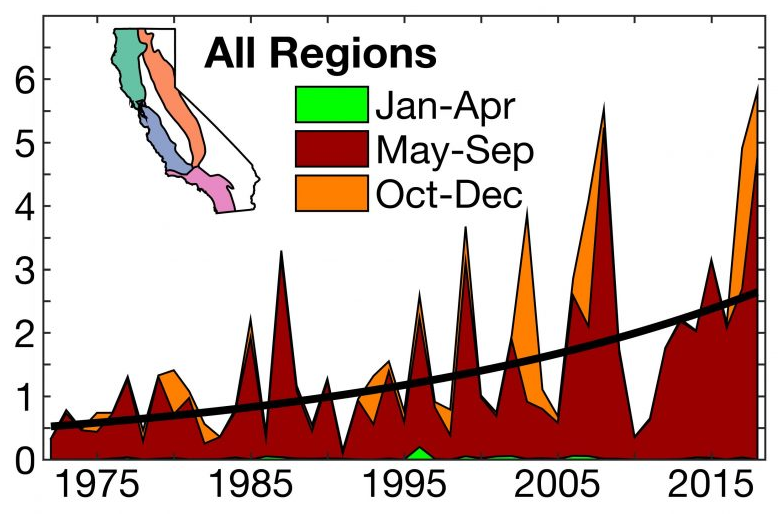

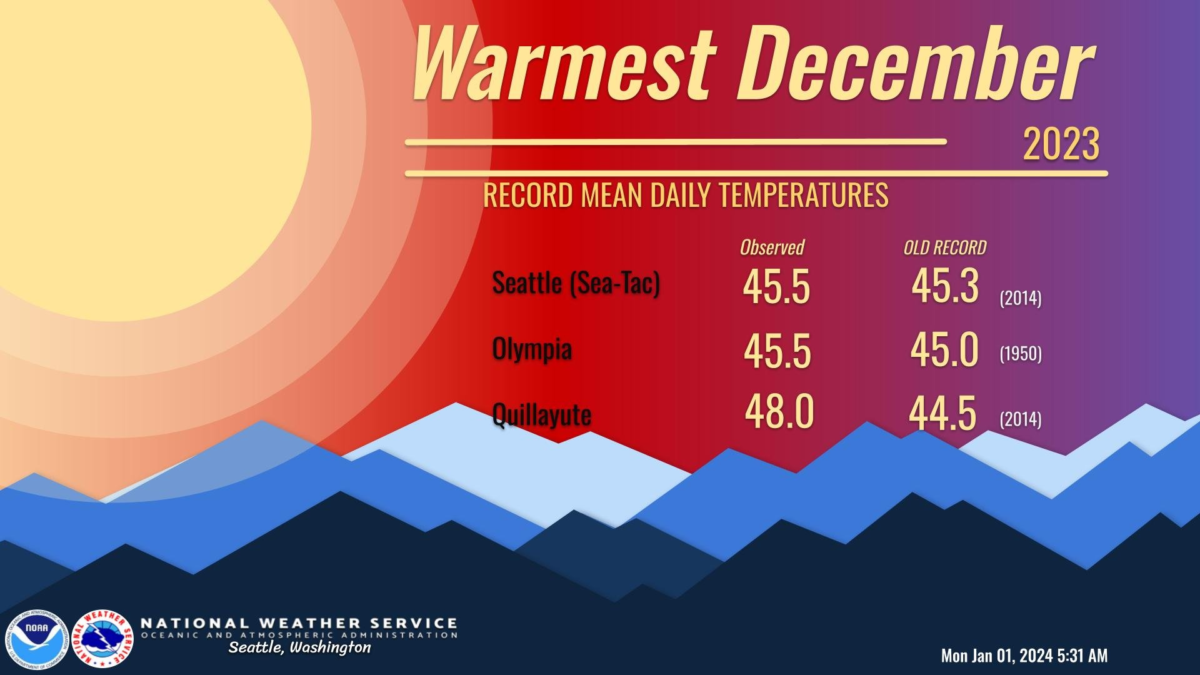

This flow is fueling alarming levels of fentanyl production, addiction, and deaths. The street drug is the top killer of Americans aged 18 to 45, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Last year nearly 75,000 people died from overdoses of synthetic opioids, mainly fentanyl. While that’s down about 2% from 2022, no other illicit drug comes close to fentanyl’s toll.

President Joe Biden has made cracking down on illicit fentanyl supply chains a priority of his administration. A key element of this effort has been prosecution. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has indicted at least a dozen Chinese chemical suppliers since mid-2023.

But at least three of those operators remained in business – and sold precursors to Reuters months after they were charged. One of these was Jenny’s company, which shipped Reuters the kilo of 1-boc-4-piperidone. In chats while arranging the sale, she scoffed at the U.S. crackdown.

“We are a powerful company,” Jenny wrote in July 2023. “This incident has no impact on us.”

In a written statement, Justice Department spokesman Wyn Hornbuckle said the DOJ and the DEA “will continue to aggressively investigate and prosecute every link in the fentanyl supply chain, including the chemical companies and executives in the People’s Republic of China supplying the ingredients used to make this deadly drug.”

A senior White House official said the administration has vigorously attacked the fentanyl scourge at home and abroad. Those efforts include jump-starting bilateral cooperation with China on the issue, making record seizures of fentanyl entering the United States, and sanctioning hundreds of foreigners involved in the drug trade. The United States is saving lives through federal approval of an over-the-counter medication that rapidly reverses the effects of opioid overdoses, the official said.

The administration is also looking to work with Congress to strengthen the reporting requirements for small shipments arriving in the United States, the official said, “so that we can better track, identify and target those packages which may contain finished pills, precursor chemicals, machinery and parts.” [more]