They turned cattle ranches into tropical forest — then climate change hit

By Justine Calma

27 April 2024

(The Verge) – Ecologist Daniel Janzen wades into the field, clutching a walking stick in one hand and a fist full of towering green blades of grass in the other to steady himself. Winnie Hallwachs, also an ecologist and Janzen’s wife, watches him closely, carrying a hat that she hands to him once he stops to explain our whereabouts.

Together with other conservationists who have dedicated decades of their lives to this place, the couple has brought forests back to the Area de Conservación Guanacaste (ACG). It’s an astonishing 163,000 hectares of protected landscapes — an area larger than the Hawaiian island of Oahu — where forests have reclaimed farmland in Costa Rica.

The grass isn’t supposed to be here. Janzen and Hallwachs only keep this small field around as a reminder of — and to show visitors like me — how far they’ve come since the 1970s, when pastures and ranches still dominated much of the landscape.

Across from the field, on the other side of a two-lane road that winds through the ACG, is one of the first stretches of young forest that Janzen and Hallwachs started nursing back to life. Tree limbs stretch out over the road, as if trying to reach the remaining patch of grass left to seed on the other side.

ACG is a success story, a powerful example of what can happen when humans help forests heal. It’s part of what’s made Costa Rica a destination for ecotourism and the first tropical country in the world to reverse deforestation. But now, the couple’s beloved forest faces a more insidious threat.

Across the road, the leaves are too perfect. It’s like they’re growing in a greenhouse, Janzen says. There’s an eerie absence among the foliage — although you’d probably also have to be a regular in the forest to notice.

“Every year it seems worse,” Hallwachs says. “We should have found bugs.”

There should have been bees, wasps, and moths along our walk, she explains. And plenty of caterpillar “houses” — curled up leaves the critters sew together that eventually become shelter for other insects. “The houses were everywhere, now it’s almost exciting when you see one,” Hallwachs says. “This is just weird.”

The bugs play crucial roles in the forest — from pollinating plants to forming the base of the food chain. Their disappearance is a warning. Climate change has come to the ACG, marking a new, troubling chapter in the park’s comeback story.

It also serves as a lesson for conservation efforts around the globe. More than 190 countries have recently committed to restoring 30 percent of the world’s degraded ecosystems under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Billionaire philanthropists are pledging to support those efforts. What’s happening here in the ACG says a lot about what it takes to revive a forest — especially in a warming world.

“When I was here earlier, a younger person, I could win a case of beer by betting on the first day that the rains would start,” Janzen tells The Verge. Now, at 85 years old, he says, “I would never dream of betting anything because it can start a month early or a month late.”

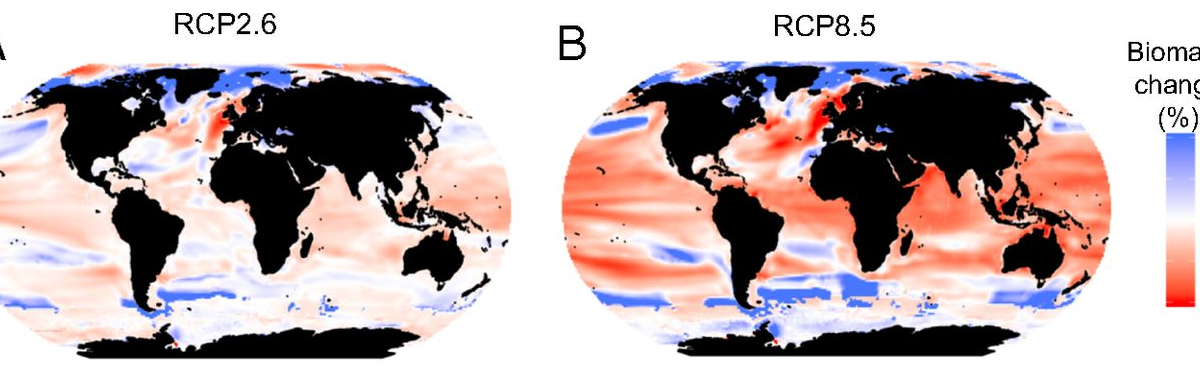

The dry season is about two months longer than it was when Janzen arrived in the 1960s. Climate change is making seasons more unpredictable and weather more erratic across the planet. And that’s posing new risks to the sanctuary scientists like Janzen and Hallwachs have created at ACG.

María Marta Chavarría, ACG’s field investigation program coordinator, describes the unpredictability as “el alegrón de burro.” Strictly translated from Spanish, it means “donkey happiness.” Colloquially, it describes a fake-out: short-lived joy from a false start.

Chavarría, who speaks with the upbeat tilt of an educator excited to teach, explains it like this, “A big rain is the trigger. It’s time! The rainy season is going to start!” Trees unfurl new leaves. Moths and other insects that eat those leaves emerge. But now, the rains don’t always last. The leaves die and fall. That has ripple effects across the food chain, from the insects that eat the leaves to birds that eat the insects. They perish or move on. And next season, there are fewer pollinators for the plants. “The big trigger in the beginning was false,” Chavarría explains. “They started, but no more.” [more]

They turned cattle ranches into tropical forest — then climate change hit