Why carbon capture is no easy solution to climate change – “Not all technologies are going to be possible in all locations”

By Leah Douglas

27 November 2023

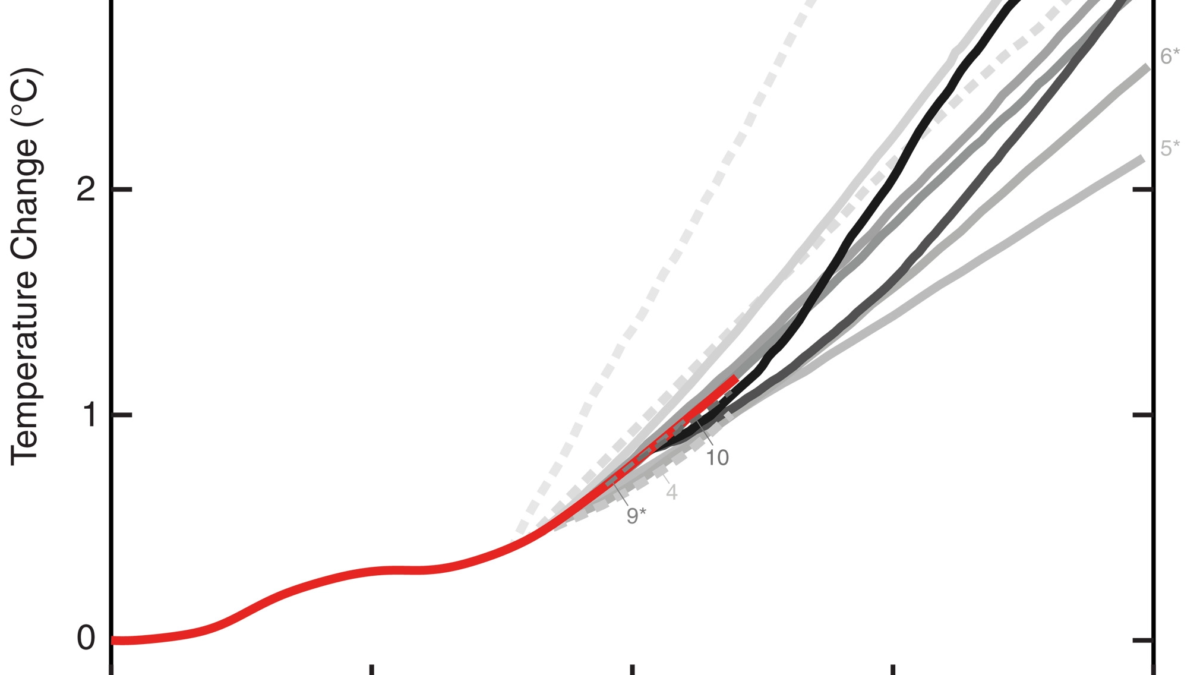

(Reuters) – Technologies that capture carbon dioxide emissions to keep them from the atmosphere are central to the climate strategies of many world governments as they seek to follow through on international commitments to decarbonize by mid-century.

But they are also expensive, unproven at scale, and can be hard to sell to a nervous public – making unworkable, at the moment, the model envisaged worldwide of capturing carbon and storing it for money.

Underscoring the current hurdles, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in a November 23 report that the oil and gas industry is relying excessively on carbon capture to reduce emissions and called the approach “an illusion,” sparking an angry response from OPEC which views the technology as a lifeline for future fossil fuel use.

As nations gather for the 28th United Nations climate change conference in the United Arab Emirates at the end of November, the question of carbon capture’s future role in a climate-friendly world will be in focus.

Here are some details about the state of the industry now, and the obstacles in the way of widespread deployment:

Forms of carbon capture

The most common form of carbon capture technology involves capturing the gas from a point source like an industrial smokestack. From there, the carbon can either be moved directly to permanent underground storage or it can be used in another industrial purpose first, variations that are respectively called carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS).

There are currently 42 operational commercial CCS and CCUS projects across the world with the capacity to store 49 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, according to the Global CCS Institute, which tracks the industry. That is about 0.13% of the world’s roughly 37 billion metric tons of annual energy and industry-related carbon dioxide emissions.

Some 30 of those projects, accounting for 78% of all captured carbon from the group, use the carbon for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), in which carbon is injected into oil wells to free trapped oil. Drillers say EOR can make petroleum more climate-friendly, but environmentalists say the practice is counter-productive.

The other 12 projects, which permanently store carbon in underground formations without using them to boost oil output, are in the U.S., Norway, Iceland, China, Canada, Qatar, and Australia, according to the Global CCS Institute.

It is unclear how many of these projects, if any, turn a profit.

Another form of carbon capture is direct air capture (DAC), in which carbon emissions are captured from the air.

About 130 DAC facilities are being planned around the world, according to the IEA, though just 27 have been commissioned and they capture just 10,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually.

The U.S. in August announced $1.2 billion in grants for two DAC hubs in Texas and Louisiana that promise to capture 2 million metric tons of carbon per year, though a final investment decision on the projects has not been made. […]

Companies investing in carbon removal need to take seriously community concerns about new infrastructure projects, said Simone Stewart, industrial policy specialist at the National Wildlife Federation.

“Not all technologies are going to be possible in all locations,” Stewart said. [more]

Explainer: Why carbon capture is no easy solution to climate change