Ten “you must be kidding” weather and climate facts of 2023

By Bob Henson and Jeff Masters

26 December 2023

(Yale Climate Connections) – The drumbeat of record weather and climate phenomena — hottest, wettest, fieriest, fiercest, and so on — can sometimes fade into the background, like the repetitive backdrop to a mournful dirge. Then there are those sharp moments, like a cymbal crash, when the atmosphere jolts us to attention. The past year has been riddled with such moments, some of them reflecting the vagaries of extreme weather and others more firmly connected to the effects of human-caused warming from fossil fuel use. Below are quick looks at some of the wildest facts about the past year’s weather and climate.

Wildfires scorched 17 times as much land in Canada as in the United States.

Wildfire tore across North America in a bizarrely bifurcated fashion in 2023. The continental area burned by U.S. wildfire — about 2.6 million acres — was the least since 1998 and only about one-third of the annual average over the past decade. This was due in large part to generous rains and mountain snows that helped keep the Southwest moist and relatively mild well into summer, as well as the unusual arrival of late-summer moisture from Hurricane Hilary (see below). On November 4, California was declared drought-free for the first time in more than three years.

Meanwhile, record springtime heat and drought dried out much of the landscape of southern and western Canada and pushed the nation’s fire season into premature overdrive. By June, destructive fires were already raging from the Canadian Rockies to Atlantic Canada, spewing massive volumes of smoke that periodically swept south into the United States and even reached Europe. Yellowknife, the second-largest city in northern Canada, was almost engulfed by flames in mid-August, forcing a three-week-long evacuation order.

The year’s total fire coverage in Canada of about 45 million acres was more than twice the previous national record, from 1995, and more than six times the yearly average over the past decade, affecting some 5% of Canada’s forest entire cover. By itself, it was more than enough to push the combined U.S./Canada fire coverage into record territory for data going back to 1983. Many parts of our warming planet — including western North America — have become more fire-prone as rising temperatures more effectively parch the landscape when drought sets in. Increased settlement in the wildland-urban interface is also adding to the threat.

Typhoon Doksuri was almost twice as costly as any other typhoon on record in China.

Typhoon Doksuri, the strongest on record to hit China’s Fujian province, made landfall there on July 28. According to Gallagher Re, the damage was at least $20 billion, making Doksuri the costliest typhoon in Chinese history, surpassing the $12 billion cost of Typhoon Lekima in 2019. According to EM-DAT, the international disaster database, the only costlier typhoon on record in the entire Northwest Pacific was Typhoon Mireille of 1991, which caused $22 billion in damage to Japan (in inflation-adjusted dollars).

Doksuri killed at least 80 people in China and 47 in the Philippines. The remnants of Doksuri dumped 744.8 mm (29.32 inches) of rainfall in Beijing over five days, setting an all-time precipitation record for the capital region since record-keeping began during the Qing dynasty in 1883. It’s also quite a bit more than Beijing typically experiences in an entire year: the city’s annual average from 1991 to 2020 was 20.78 inches.

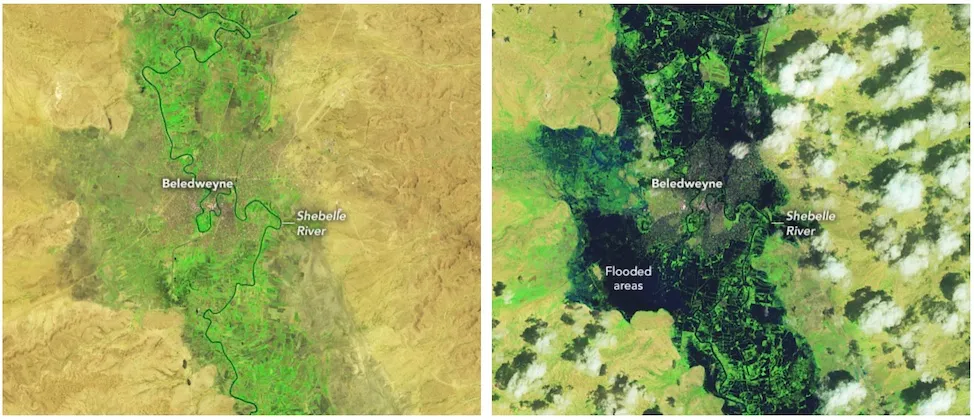

Somalia lurched from catastrophic drought to deadly flooding in less than a year.

As the Eastern Pacific switched this year from a multiyear La Niña event to the strong El Niño event now underway, rainfall patterns made a U-turn in some parts of the world. The reversal was especially dramatic in hard-hit Somalia. During the unusually protracted La Niña conditions, eastern parts of the Horn of Africa region (Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia) experienced their most prolonged drought in records going back to 1950. In Somalia alone, the drought led to 43,000 excess deaths from 2021 through 2022, according to a February 2023 study by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The study warned that the rate of fatalities could rise and predicted an additional 18,100-34,200 drought deaths in Somalia during the first half of 2023. If this estimate proves correct, then the Somalia drought will be the deadliest weather-related disaster of 2023.

An analysis from World Weather Attribution released April 27 found that the October-to-December “short rains” have been getting wetter over time, even with La Niña’s drying influence taken into account, while the March-to-May “long rains” (which are uncorrelated with La Niña) have been getting drier. The extremity of drought impacts produced by low rainfall plus heat-induced landscape drying in 2021-2022 was far more severe in today’s climate than in the preindustrial climate, the study found, mainly due to the long-term warming of 1.2°C. “A conservative estimate is that such droughts have become about 100 times more likely,” the report added. It also noted that climate change is expected to intensify drought impacts as well as flood-producing rains in the region: “Taken together, regional climate variability and the projections indicate the need to invest in adaptation strategies that are robust to both wet and dry extremes.”

Late in 2023, as La Niña segued into El Niño, rain finally arrived — but too much of it — to parts of the Horn of Africa, including up to four times the average October-November rainfall. By late November, the most widespread and destructive floods in more than 20 years had led to nearly 100 deaths in Somalia and 76 deaths in Kenya. Almost 700,000 people in Somalia were displaced, according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network. A December 7 analysis from World Weather Attribution found that the exceptional intensity of the rains could be attributed in roughly equal parts to human-induced climate change and to a strong positive phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole, a naturally occurring phenomenon similar to the El Niño–Southern Oscillation. [more]