The climate contradiction that will sink us – “We already have a refugee crisis; I shudder to think what would happen if everyone living within two meters of sea level would be displaced.”

By Zoë Schlanger

10 November 2023

(The Atlantic) – You’d be forgiven for thinking that the fight against climate change is finally going well. The clean-energy revolution is well under way and exceeding expectations. Solar is set to become the cheapest form of energy in most places by 2030, and the remarkable efficiency of heat pumps is driving their own uptake now. Sales of electric vehicles could surpass those of gas-burning cars in the next six years. The world’s biggest powers are putting huge sums toward infrastructure to usher in some form of energy transformation. Pledges are being made; legislation is being passed. The world, it seems, is finally lurching in the right direction.

But none of that is enough, practically speaking, because of one enormous hitch: The world is still using more energy each year, our consumption ticking ever upward, swallowing any gains made by renewable energy. Emissions are still rising—more slowly than they used to but, nonetheless, rising. Instead of getting pushed down, that needle is fitfully jiggling above zero, clawing into the positive digits when it needs to be deeply pitched into the negative. We are, in other words, simply not making a dent.

And so we are now in climate purgatory. In this zone, countries and companies are doing the right things to steer away from the damages of climate change, but are at the very same time making deliberate choices that swamp the effect of those other, better things. The International Energy Agency predicts that demand for fossil fuels will peak by 2030. Yet a report released by the United Nations and several climate organizations this week found that governments in aggregate still plan to increase coal production until 2030, and oil and gas production until at least 2050, global net-zero agreements be damned. In total, countries that hold the world’s oil, gas, and coal deposits still plan to produce 69 percent more fossil fuels than is compatible with keeping warming under 2 degrees Celsius, the riskier cousin to the 1.5-degree-Celsius goal each of those countries pledged to aim for. Many experts now consider that goal impossible, because of global reluctance to phase out fossil fuels. One expert who worked on the UN report called this “insanity,” a “climate disaster of our own making.” The climate math is not adding up.

Perhaps you’ve suspected this. One hardly needs to look out the window to register the effects of these choices. This year of fires and floods is on track to be the hottest year on record. And the global ocean, which absorbs the preponderance of the excess energy in the global system, is heating at an accelerating rate; the ocean was the warmest on record in August 2023, according to NOAA. In all likelihood, with El Niño persisting into the new year, 2024 will probably be even warmer.

The scientist James Hansen, famous for his early warnings about climate change, suggested in a paper released last week with a suite of high-level colleagues that warming is accelerating more rapidly than is presently understood: In their view, that the Earth could exceed 1.5 degrees of warming this decade is practically assured, and 2 degrees by 2050 is likely unless the world eliminates fossil-fuel use far faster than planned. These new calculations are a reflection of just how many variables go into making the livable conditions we call “the climate,” and how messing with one, even with good intentions, can have cascading effects. Part of the problem, these researchers found, was that regulations passed to reduce harmful sulfate-aerosol emissions from shipping vessels worked. Sulfate aerosols are bad for human health. But they also reflect solar radiation back into space, so less pollution also means that the Earth is absorbing that much more energy and heating up that much faster. “That’s why global warming will accelerate. That’s why global melting will accelerate,” Hansen said at a press conference.

Some fellow climate scientists found the paper’s exact predictions questionable, calling them too alarmist and arguing that the temperature will take a bit longer to change. But even if researchers disagree on the details, their worry over our climatic future is apparent. Their usual tone of reserve is melting away. Typically circumspect scientists are beginning to sound desperate, the despair leaking out in their exhortations to the public to take climate change for the emergency it is. They are publicly mourning the species they study: the emperor-penguin scientist facing down the loss of her subjects, the coral-reef scientist recognizing that no reef is safe from bleaching. One climate scientist, Zeke Hausfather, called recent global temperature data “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.” Whichever way you cut it, global warming is already happening too fast to generously support life, which our prior climate did quite well. As a feebly supportive climate devolves into an unsupportive one, it won’t matter who forecasted the timing right, only that we missed our chance at the good version of Earth.

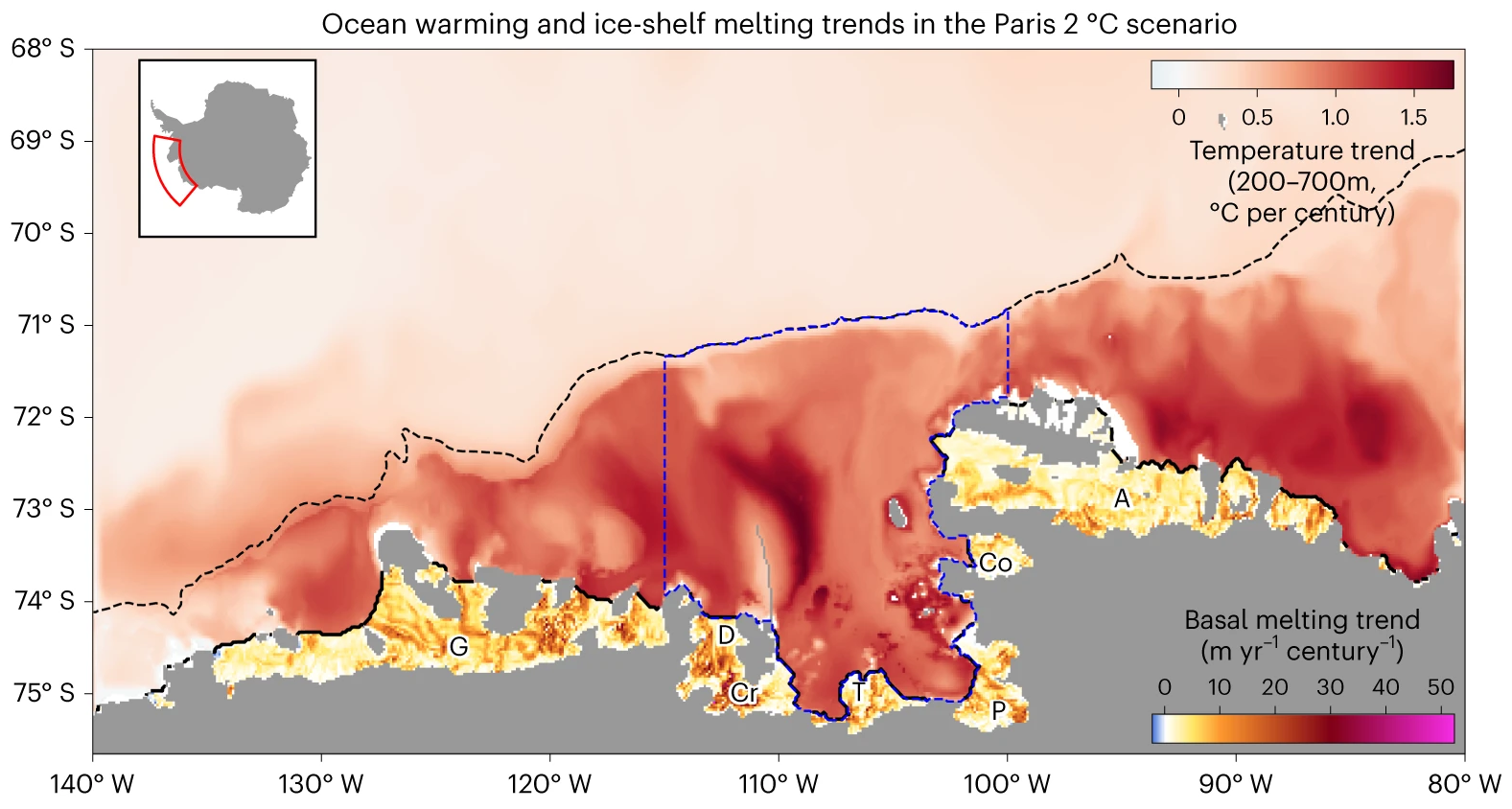

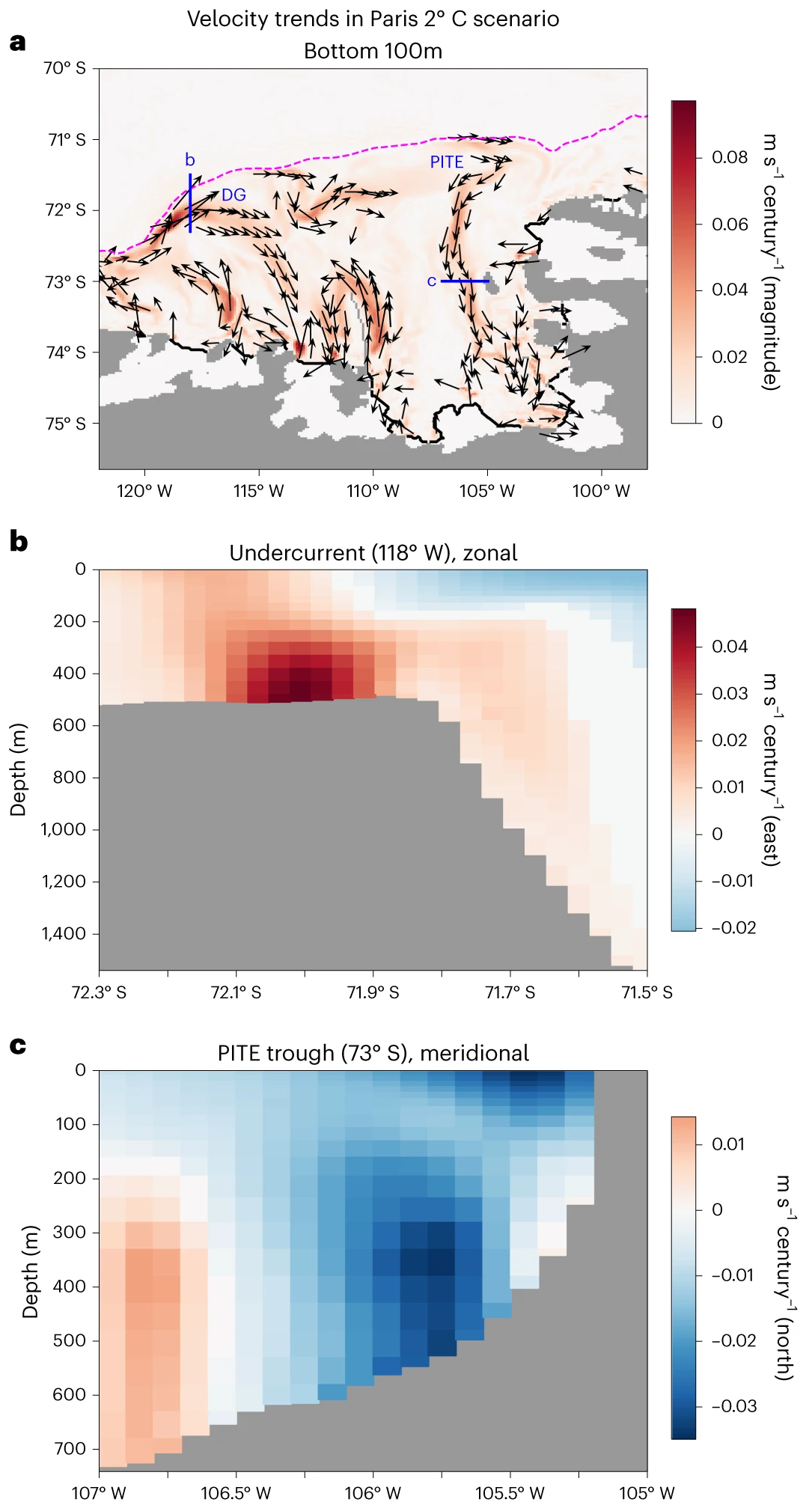

And that is where the math is still pointing: Emissions tick up, global temperatures tick up, and the consequences unfold. Kaitlin Naughten, an ocean-ice modeler for the British Antarctic Survey, co-authored a paper in the journal Nature last month warning that the loss of much of West Antarctica’s ice sheet is now virtually inevitable. Even if future emissions are drastically curtailed, enough warming is probably locked in to wash the bulk of the sheet away. At best, she says, we are on the brink of its total loss becoming assured. The exact timing of the sheet’s total disappearance, too, is unclear. But by one estimate, the West Antarctic ice sheet contains enough water to raise sea level globally by just over five meters, or 17 feet. At the very least, Naughten told me, she thinks it would be wise to plan for two to three meters of sea-level rise, or six to ten feet, in the next couple of centuries. “We already have a refugee crisis; I shudder to think what would happen if everyone living within two meters of sea level would be displaced,” she added. That “everyone” is projected to include some 410 million by 2100.

“I think as a climate scientist you get used to screaming into the void. You get used to people just ignoring you,” Naughten told me. Previous studies have warned of the ice sheet’s collapse if emissions were not drawn down; hers now suggests that we’ve passed the point of no return, that even significant emissions cuts would be too late for this particular ice sheet. (The East Antarctic ice sheet, she said, is far more stable—and good thing, because it contains enough frozen water for 10 times the amount of sea-level rise as its western counterpart.) As the global community prepares for COP28, the next round of international climate negotiations that begins later this month, France, Ireland, Kenya, Spain, and 12 other countries have called for a global accord to phase out fossil-fuel production. There is little doubt that this is necessary; adding more fossil fuels to the pipeline is quite obviously counterproductive to slowing, then stopping, climate change.

Yet in the U.S. alone, a country responsible for at least 20 percent of historical emissions, the current buildout of liquified-natural-gas infrastructure, intended to export the country’s plentiful gas, is the largest fossil-fuel expansion proposed in the world—and it’s happening under a president who recently passed the most impactful climate legislation the country has ever seen. That climate math isn’t adding up. China, which is responsible for about 12 percent of historical emissions according to Alex Wang, who studies Chinese environmental governance at UCLA, has one of the largest clean-power programs in the world. But the country is at the same time dramatically expanding its coal production.

Right now, these disjuncts are allowed to persist as if they are not contradictions: In the places still extracting and using the most fossil fuels, like the U.S., leaders aren’t yet paying that steep a political price for promoting clean energy or pursuing climate action while simultaneously promoting and pursuing policies that have the exact opposite ends. But at some point, that internal contradiction must become so obvious to the average citizen, or so untenable in the face of the damage it has done, that one way or another it collapses. And only when it does will the world have a real chance at closing off the widening gyre of loss that is coming for us.

Oddly enough, the difference between the world we have and the one we could have is buried in two contrasting modeling reports by two of the world’s most important energy-information organizations. Whereas the International Energy Agency projected that we’d hit peak fossil-fuel use in 2030, the U.S. Energy Information Administration came to a very different conclusion: It saw demand for fossil fuels rising through at least 2050. The difference between the two agency’s models is how they treat government policy. “It’s important to understand we are modeling exactly what’s on the books as it is written,” Michelle Bowman, a senior renewables analyst at the U.S. EIA, told me. If a policy is set to expire, the U.S. EIA treats it as expiring. It doesn’t take into account policies that countries have talked about but have had yet to implement. The international agency’s analysis, in contrast, assumes countries will follow through with more climate-friendly policies and renew the ones they already have on the books. “Look how different things could be,” Bowman said. The difference is night and day, despair and hope.

Policy, and only policy, appears to make that difference. It represents the choices that our leaders make about when to finally change course. Naughten, the Antarctic-ice scientist, reminded me that “climate is a spectrum; it isn’t an on/off switch.” Whenever we do make a different set of decisions, ones that make the math properly compute, we will be saving what we have left, preventing some layer of livability from being irrecoverably sloughed off and swept away.