Forests are no longer our climate friends – “As extreme as this year’s wildfire emissions have been, they are just the latest escalation in a multi-decade flood of CO₂ pouring out of Canada’s ‘managed’ forests and forestry”

By David Wallace-Wells

6 September 2023

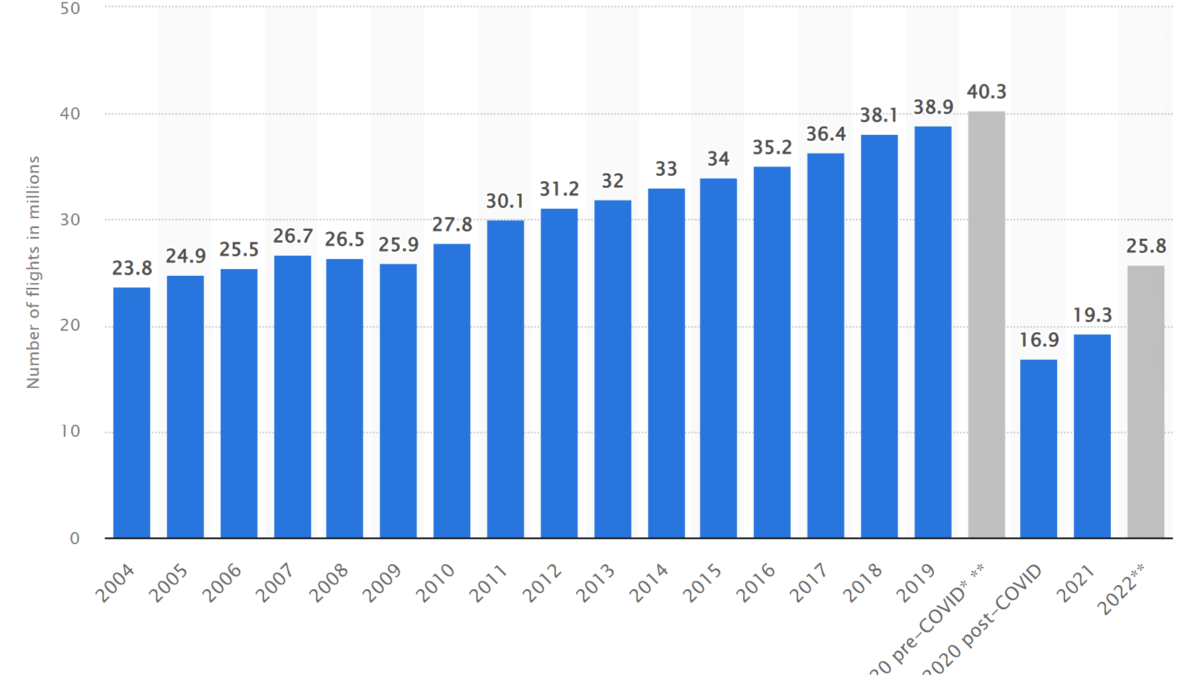

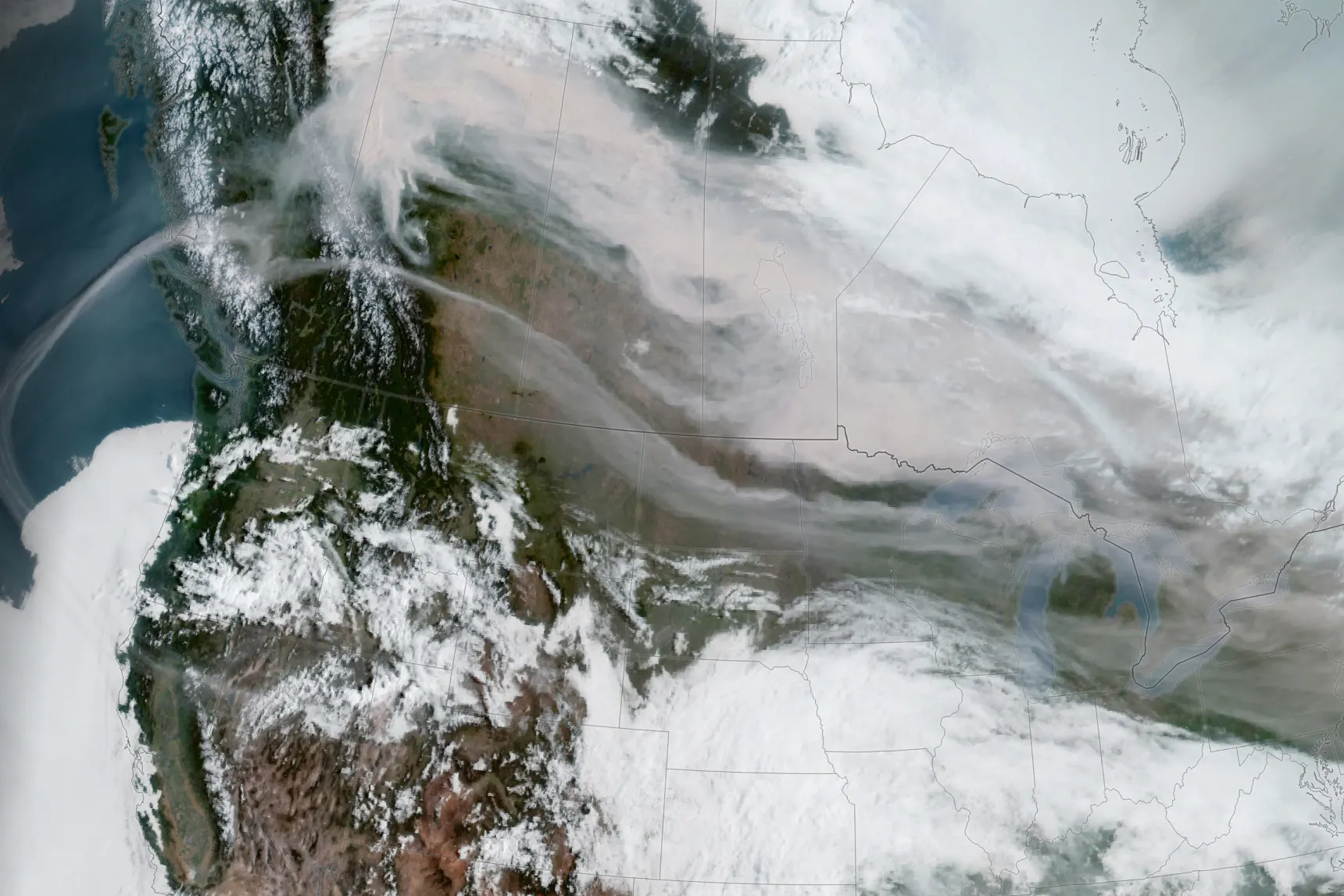

(The New York Times) – Canadian wildfires have this year burned a land area larger than 104 of the world’s 195 countries. The carbon dioxide released by them so far is estimated to be nearly 1.5 billion tons — more than twice as much as Canada releases through transportation, electricity generation, heavy industry, construction and agriculture combined. In fact, it is more than the total emissions of more than 100 of the world’s countries — also combined.

But what is perhaps most striking about this year’s fires is that despite their scale, they are merely a continuation of a dangerous trend: Every year since 2001, Canada’s forests have emitted more carbon than they’ve absorbed. That is the central finding of a distressing analysis published last month by Barry Saxifrage in Canada’s National Observer, ominously headlined “Our forests have reached a tipping point.”

In fact, Saxifrage suggests, the tipping point was passed two decades ago, when the country’s vast boreal forests, long a reliable “sink” for carbon, became instead a carbon “source.” In the 2000s, the effect was relatively small. But so far in the 2020s, Canada’s forests have raised the country’s total emissions by 50 percent.

“There is this feel-good myth in Canada that our massive forest is offsetting some of our massive fossil fuel emissions,” Saxifrage writes. “That might have been true decades ago under our old, stable climate. But we’ve so weakened our forest — through decades of business-as-usual industrial logging and fossil-fueled climate shifts — that it has switched to hemorrhaging CO₂ instead of absorbing it.”

And, in theory at least, there is a lot more to hemorrhage: Saxifrage calculates that the 3.7 billion tons of carbon dioxide released by Canada’s forests since 2001 are only a small fraction of the 100 billion tons stored in its trees and soil. The trends there are not encouraging. “As extreme as this year’s wildfire emissions have been,” he says, “they are just the latest escalation in a multi-decade flood of CO₂ pouring out of Canada’s ‘managed’ forests and forestry.”

This is not a simple story of wildfire and climate change but also of logging and forest management. Roughly speaking, when trees logged and trees replanted and regrown are in balance, a forest’s ability to absorb carbon is stable. But beginning in the early 2000s, twice as much carbon-absorbing ability was destroyed through logging as was regenerated by replanting. In the decades since, the forest has largely stopped regenerating at all. In the 1990s Canadian forests were sequestering 165 million tons of carbon each year, 20 million more than the carbon-storage loss by logging. In the 2010s those same forests released 35 million more tons of carbon each year than they stored, not including the additional carbon released by logging. In the 2020s, that number has grown to 180 million tons released annually.

It all seems very Canadian. This is a country that promotes itself as a soft-spoken environmentalist leader, endowed with an endless forest landscape, but which nevertheless expands its pipelines, mocks the idea of leaving fossil fuels in the ground and routinely arrests climate activists. Canada is one of the few countries with more per capita emissions than the United States; in fact, its overall carbon production has actually grown since 1990, with the country producing more than 20 percent more carbon dioxide in 2019 than it did three decades earlier. This year, in the hellish midst of its worst fire season in modern history, Alberta actually hit pause on new renewable energy projects — a pause that may derail 118 projects worth $33 billion. […]

But in recent months carbon offsetting has begun to look like an outright sham, with reports illustrating the emptiness of a vast majority of programs, particularly those that pay skimpily for poorly monitored projects in the developing world.

In one particularly scathing review in Science, researchers estimated that only 6 percent of 89 million carbon offsets would be associated with real carbon reductions. My colleague Peter Coy recently noted that the British bank Barclays suggested that the cost of offsets had fallen by more than three-quarters in just a year, a reflection of how little faith those buying them have in their reliability; voluntary carbon markets are shrinking for the first time in seven years out of growing skepticism. And last month in The Guardian, Patrick Greenfield speculated that carbon-credit speculators stood to lose many billions as the world came to realize that nearly all of the offsets being sold were “worthless.” A 2020 study showed that much-celebrated offsets sold for the Brazilian Amazon had barely slowed deforestation there. And a white paper published this summer by Joe Romm argued that the whole project of mitigating emissions through carbon offsets using forest replantation was “unscalable, unjust, and unfixable.” [more]