Summer in the Southern U.S. is becoming unbearable – “This is how it’s going to be: Things will get hotter, storms will get worse, wildfire smoke will get more common. All the while, the ruts of inequity will be worn deeper, the same people time and time again placed on the front lines of catastrophe.”

By Olivia Paschal

1 July 2023

(The Atlantic) – A few weeks ago, as the first wave of smoke from the Canadian wildfires rolled south, I was getting ready to drive from Charlottesville, Virginia, about 18 hours west to my hometown of Rogers, Arkansas, to visit family. I figured that by the time I hit the Virginia–North Carolina border, where I was planning to camp, I would have outrun the haze. But it followed me past the campsite and along I-40 in Tennessee, all the way to my corner of Arkansas, just 20 minutes away from Oklahoma. The smoke felt much like these past years of extreme weather in the South have—heavy, muddling, inescapable.

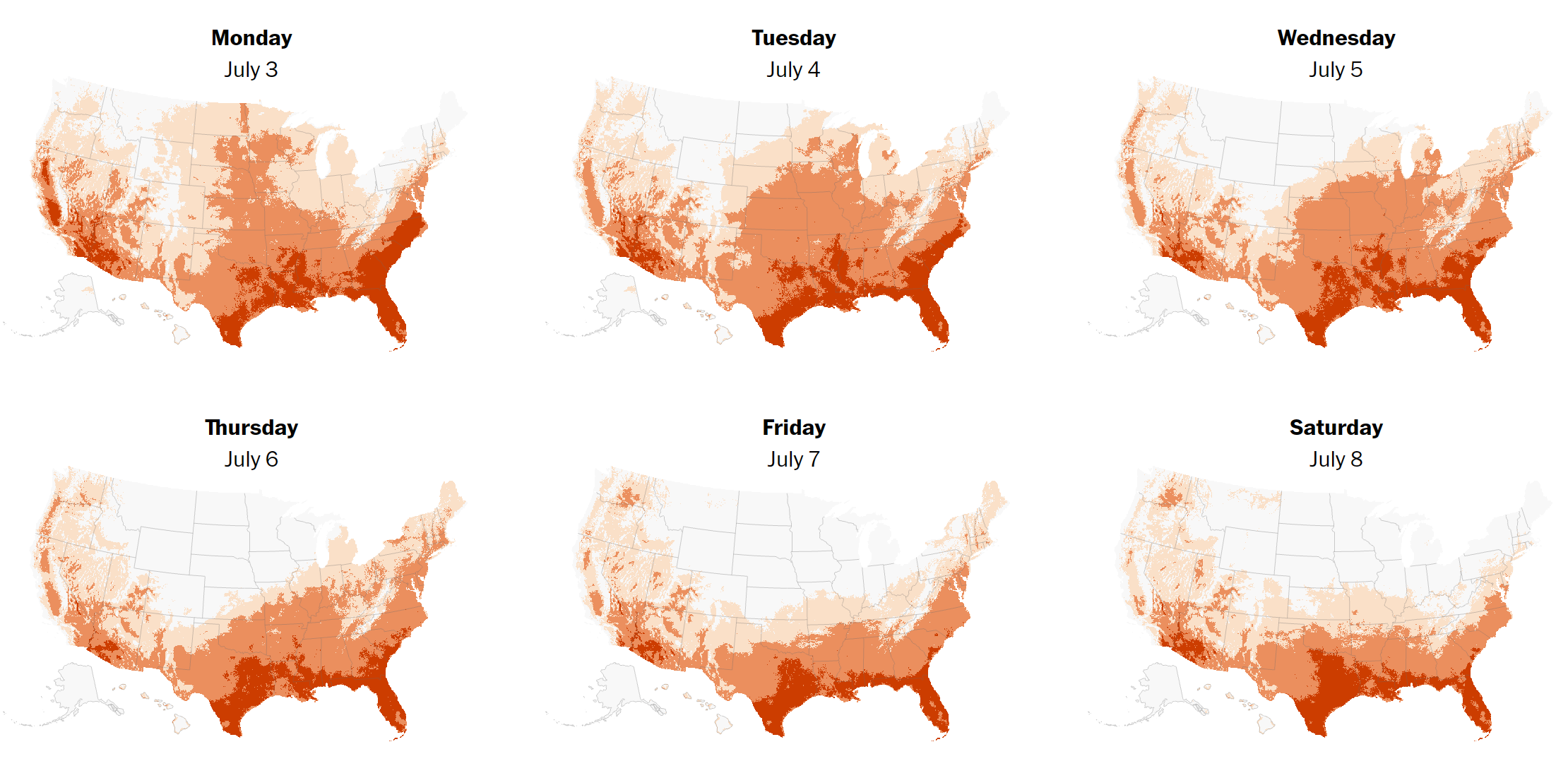

This week, more wildfire smoke washed over Charlottesville and much of the South. Meanwhile, communities wilted under a heat wave, rattled from thunder, and flooded with rain. Towns in central Arkansas hit by severe thunderstorms last weekend were facing excessive heat advisories and worse-than-normal air quality by the end of this week. Last Monday, I watched hail batter my car. Within an hour, the sun was back out and I was picking peaches in my friends’ garden, pulling off my sweatshirt because the heat had become so fierce.

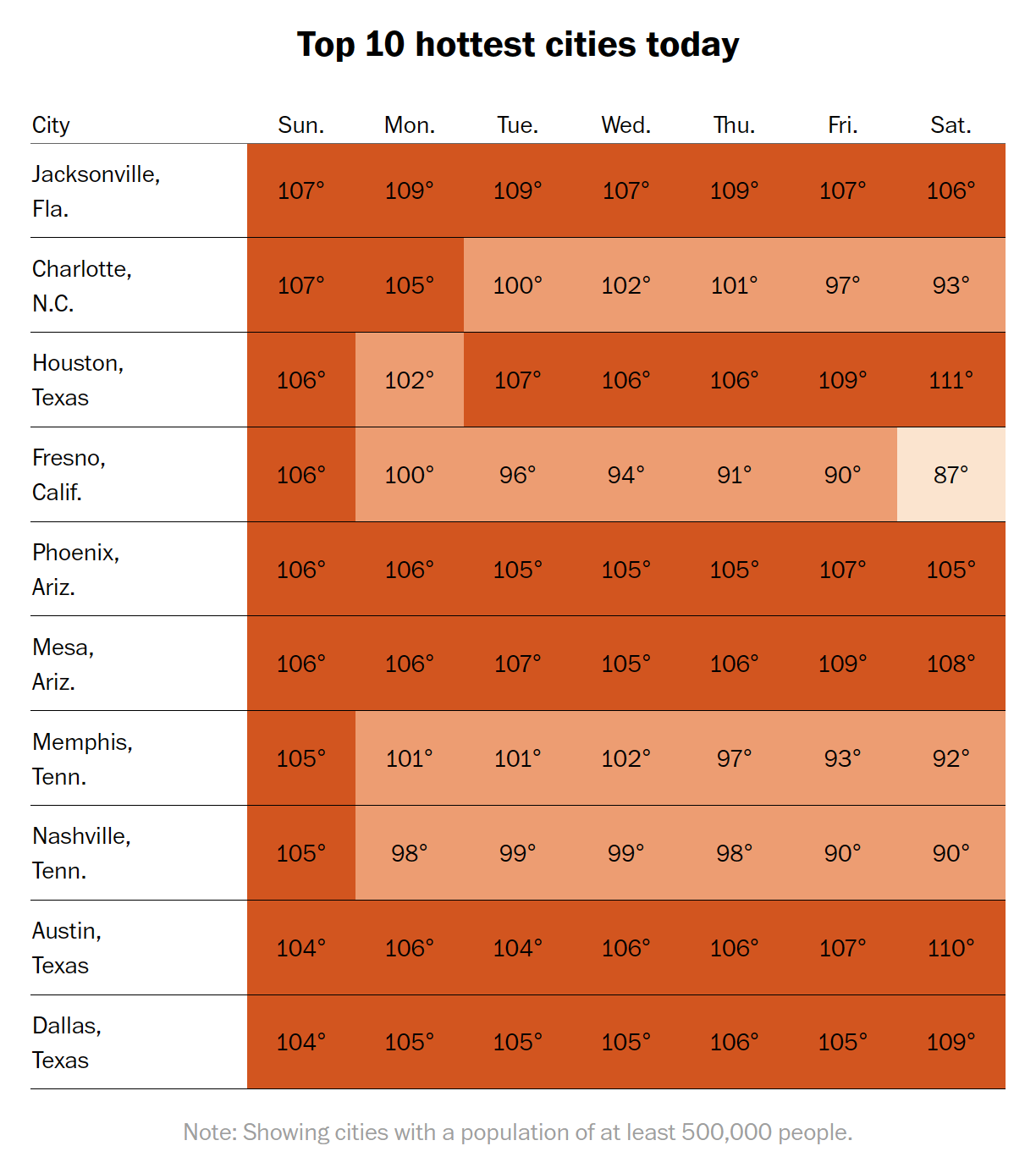

Friends in Texas who were facing deadly cold earlier this year are now seeking respite from temperatures that threaten to hit 115 degrees. In some Texas cities, the heat index has surpassed 125 degrees, dangerously high for the elderly, the unhoused, and people who have conditions like asthma. Several people have died from the heat, including Tina Perritt, a woman in Louisiana who spent days without power.

Southern summers have always been hot and humid. But the swings from one extreme to the next—drought to torrential rain, record-breaking cold to sweltering heat, storm to sun—have lately begun to feel apocalyptic. Summer is our season, the South at its best. But this new reality has taken the best parts of southern summers and made them unbearable.

The extremities feed into one another: The heat breeds severe thunderstorms in some parts of the country, and lights forests on fire in others; homes and cars are damaged, power is knocked out, and people are stranded. Power has become a particular issue in Texas, where the grid has been stretched past its limits by cold snaps over the past several winters as well as the current heat wave; right now, the saving grace is additional solar power from the beating sun, aided by wind power. And when the lights go out or the pipes burst, families are left to deal with the continued and increasing heat with no air conditioner, perhaps no water.

Growing up in Arkansas, I came to expect power outages during specific seasons: winter ice storms, March tornado warnings. These days, the disasters—because what else can they be called?—feel more frequent, less familiar. A tornado hit my parents’ house in October a few years ago. Earlier this week, some friends and I tried to escape the heat by floating the Rivanna River, and spent three hours drifting through wildfire haze, trying not to acknowledge that in escaping one hazard we’d exposed ourselves to another.

Climate change amplifies these disasters, and economic precarity exacerbates their impacts for many, especially the unhoused, the elderly, the incarcerated. Connie Edmonson, a 78-year-old woman in rural Everton, Arkansas, recently missed an electricity payment for her mobile home because she was paying medical bills for her heart and breathing problems. The heat had put her in danger before—she’s had several heat strokes, and earlier this year, she passed out while she was mowing her lawn. A neighbor had to help her up and back inside (and finish the mowing). If it hadn’t been for Legal Aid and her doctor working together to persuade her electricity provider to turn the power back on before temperatures escalated again this week, she said, “I don’t think I would have made it.”

The South is a region rutted with inequities, and every time the pendulum of climate change swings from extreme heat to extreme cold, it deepens the grooves. Laborers are especially vulnerable. The South’s agricultural economy, propped up for centuries by enslaved Black workers, now relies on farmworkers—and because of lobbying by segregationist southern lawmakers, those workers are exempt from the National Labor Relations Act. No federal regulations protect farmworkers—who are mostly noncitizen immigrants from Latin America, commonly live under the poverty line, and have few legal rights—from extreme heat. Farmworkers die from heat-related injuries at 20 times the rate of other laborers. A 2020 study estimated that the number of days farmworkers labor in extreme heat will double by mid-century. The state of Texas just rescinded rules requiring water breaks for construction workers, exposing them to greater risk of dehydration and heat stroke.

For workers, the growing heat is impossible to ignore. Carlos Herrera Fabian is a 22-year-old who grew up in a farmworker family that moved up and down the East Coast, from Florida to Maine, picking seasonal crops. “Back then, you could say that the heat was tolerable,” he said. “Now it’s just scorching. You can feel your eyes burning from the sweat dripping down.” Fabian’s 72-year-old grandfather, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, still works in the Florida fields, and comes home looking like he’s just taken a shower, with sweat streaming down his body. Farmworkers generally wear long-sleeve shirts and pants to protect themselves from sun and pesticides, exacerbating the effects of the heat. And they don’t get paid when extreme thunderstorms keep people out of the fields, or drought ruins crops.

Federal—and state—labor laws would help protect against these conditions. So would better infrastructure: power grids, tree canopies, cooling shelters, readily available water. The inequities manifest in cities too. Low-income, redlined neighborhoods have more concrete and fewer trees—and, as a result, summer temperatures up to 20 degrees higher—than wealthier, whiter ones.

This is how it’s going to be. Things will get hotter, storms will get worse, wildfire smoke will get more common, cold snaps will persist. All the while, the ruts of inequity will be worn deeper, the same people time and time again placed on the front lines of catastrophe. Power grids will continue to fail, especially in states where the government is reticent to fund infrastructure even for the wealthy and white, let alone for the poor, the rural, the people of color. The layering haze-on-hail-on-heat sometimes weighs so heavy that it can feel hopeless, like southern summers will never be southern summers again. And they won’t. But together we will try to stymie the damage.

One Response

Comments are closed.