Eurasia Group’s Top Risks for 2023 – “The risks this year are the most dangerous we’ve encountered in the 25 years since we started Eurasia Group”

By Ian Bremmer and Cliff Kupchan

3 January 2023

(Eurasia Group) – Russia has no way to win in Ukraine. The European Union is stronger than ever. NATO rediscovered its reason for being. The G7 is strengthening. Renewables are becoming dirt cheap. American hard power remains unrivaled. Midterms in the United States were decidedly normal … and many of the candidates posing the biggest threat to democracy (especially those who would have had authority over elections) lost their races. Meanwhile, Donald Trump is the weakest he has been since he became president, with a large number of Republicans preparing to take him on for the GOP nomination.

There’s got to be a catch.

The big one: A small group of individuals has amassed an extraordinary amount of power, making decisions of profound geopolitical consequence with limited information in opaque environments. On a spectrum of geopolitics with integrated globalization at one extreme, these developments are at the other extreme, and they’re driving a disproportionate amount of the uncertainty in the world today.

Our top risks this year are skewed toward these actors and their impact: Rogue Russia, Maximum Xi, Weapons of mass disruption, and Iran in a corner all come from international actors facing severe structural challenges and strong opposition (internal and/or external) in achieving their desired goals, with neither oversight, adequate expert inputs, nor checks and balances constraining their actions.

Dictatorships are stumbling at the same time that they’re becoming more consolidated. Vladimir Putin’s Russia is too isolated for its leader to attend the G20 summit, facing serious economic and military decline … while NATO has never looked stronger. Iran, Russia’s most important military ally, faces a deeply hostile geopolitical environment alongside the greatest domestic unrest since the 1979 revolution that brought the Islamic Republic to power. China was thoroughly unprepared for its troubles with zero Covid (our #1 risk last year), leading to unprecedented demonstrations … and a sudden turnaround of President Xi Jinping’s policy, ending restrictions two years after the Americans and Europeans. Their trajectories are, to varying degrees, increasingly unsustainable.

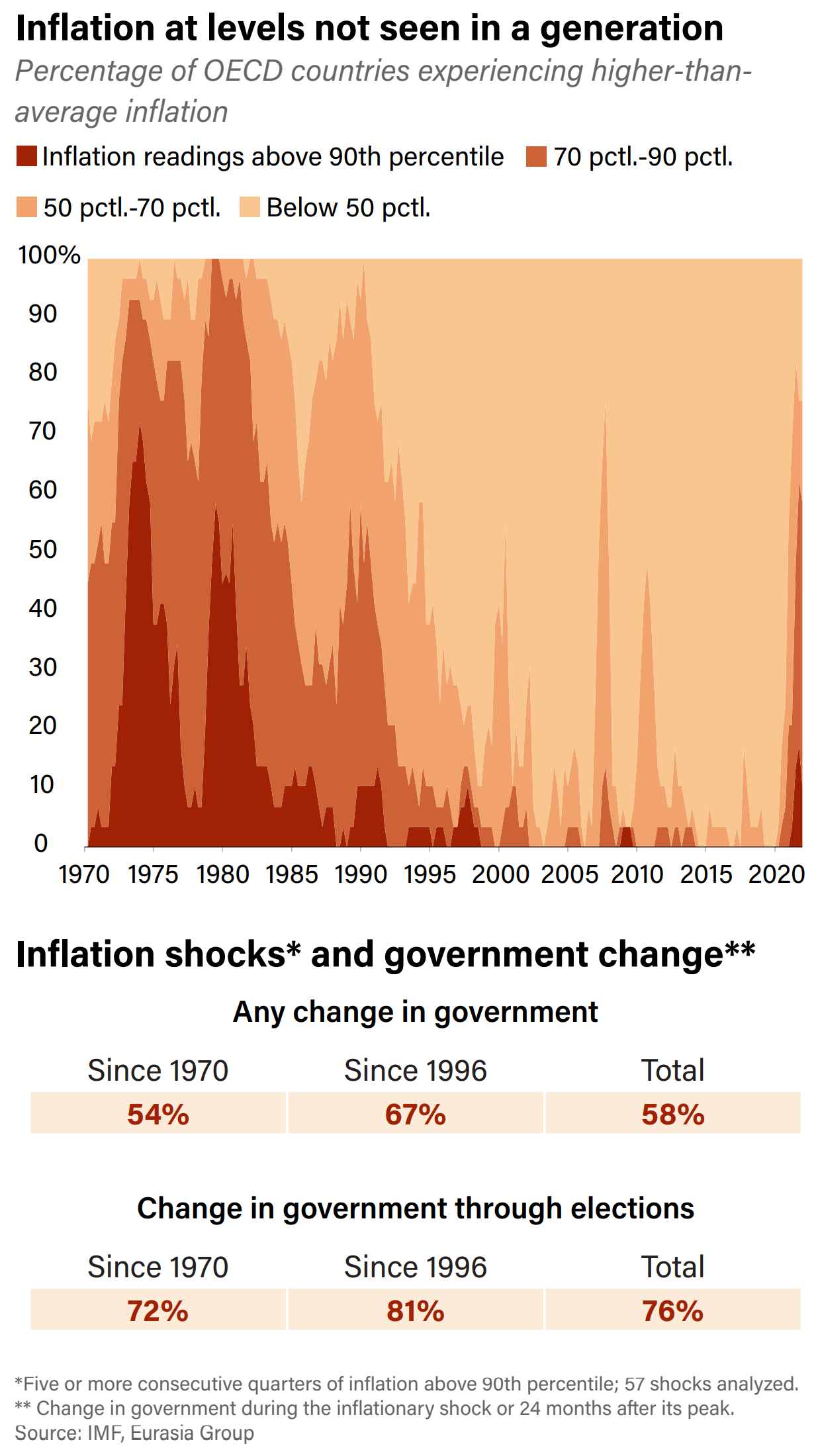

More broadly, progress in human development has been thrown into reverse by a global pandemic, a land war in Europe, a massive inflationary shock, and mounting climate catastrophe. After decades of globalization pushing unprecedented global growth and the emergence of a robust global middle class, we are now seeing a majority of the world’s 8 billion people fare worse, not better, in education levels, life expectancy, economic well-being, and safety and security. The headwinds for human development will grow in 2023.

American leadership is a double-edged sword. One year into Russia’s failed war, the United States has only gained as the world’s sole global military leader. Core allies clearly recognize their reliance on the United States for national security, broadly defined. America’s comparative economic power is stronger coming out of the pandemic and through the Russia war than after the global financial crisis in 2008. Whispering in Europe has gotten louder that the global position of the United States is benefiting from the war, while the Europeans and Japan face deindustrialization and a permanent end to the peace dividend. China, too, faces massive economic challenges, much greater than other major countries. Its economy is still expected to surpass that of the United States in GDP by 2030, but there is a growing chance it never does. And if it does, this does not herald a Chinese century as China’s population halves by 2100. If any major middle-income country is truly outperforming in the coming decades, it’s the world’s soon-to-be third largest economy (and its largest democracy), India.

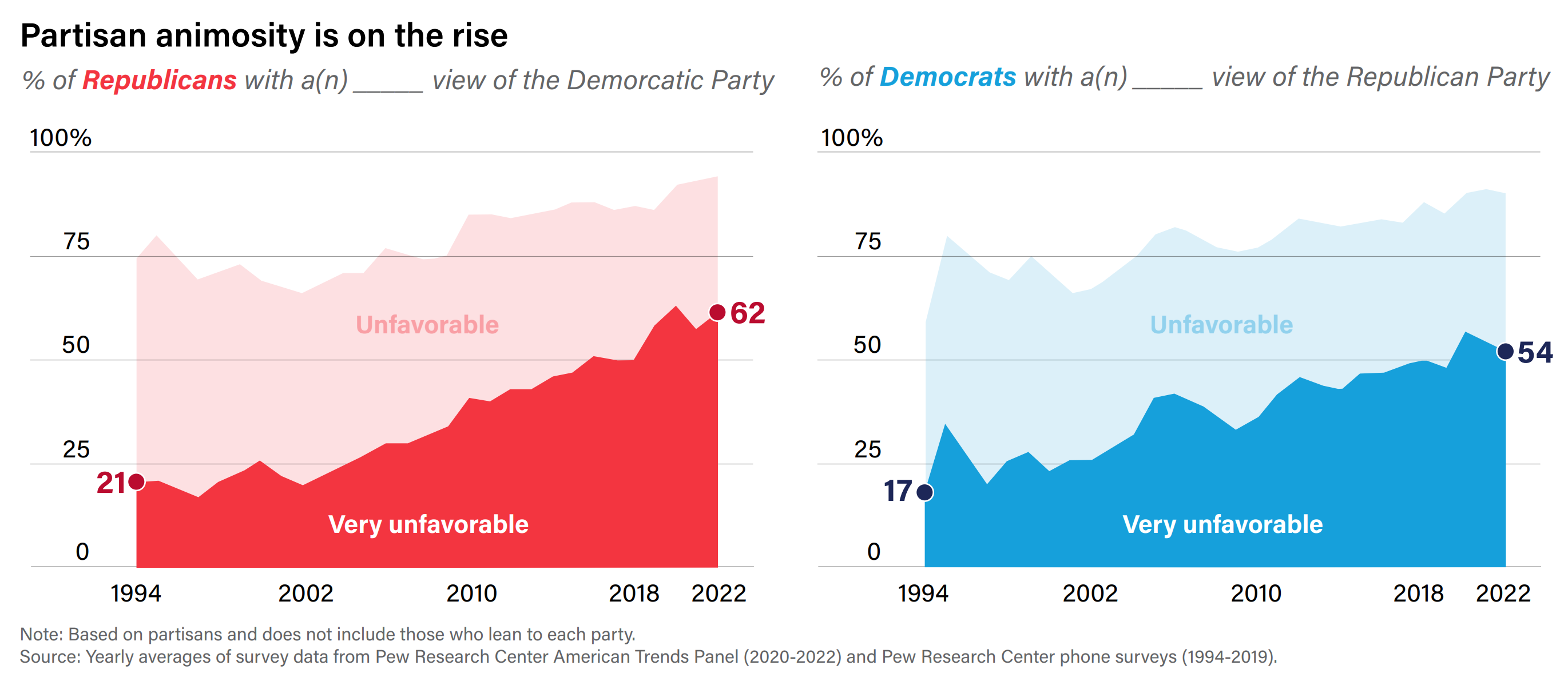

But in terms of leading by example, it’s a radically different story for the United States. In 1989, the US was the world’s leading exporter of democracy. Today, it is the leading exporter of tools that undermine democracy—the result of algorithms and social media platforms that rip at the fabric of civil society while maximizing profit, creating unprecedented political division, disruption, and dysfunction. That trend is accelerating fast—not driven by governments but by a small collection of individuals with little understanding of the social and political impact of their actions.

Is the tech centibillionaire a bigger threat to global instability than Putin or Xi? It’s unclear but the right question to ask and a critical challenge for the world’s democracies, highlighting the vulnerability of representative political institutions and the growing allure of state control and surveillance. As we showed with the J Curve back in 2006, open societies were the most stable, in part because technology strengthened them and weakened authoritarian regimes. In 2023, less than two decades later, the opposite is true.

It’s not the end of democracy (nor of NATO or the West). But we remain in the depths of a geopolitical recession, with the risks this year the most dangerous we’ve encountered in the 25 years since we started Eurasia Group.

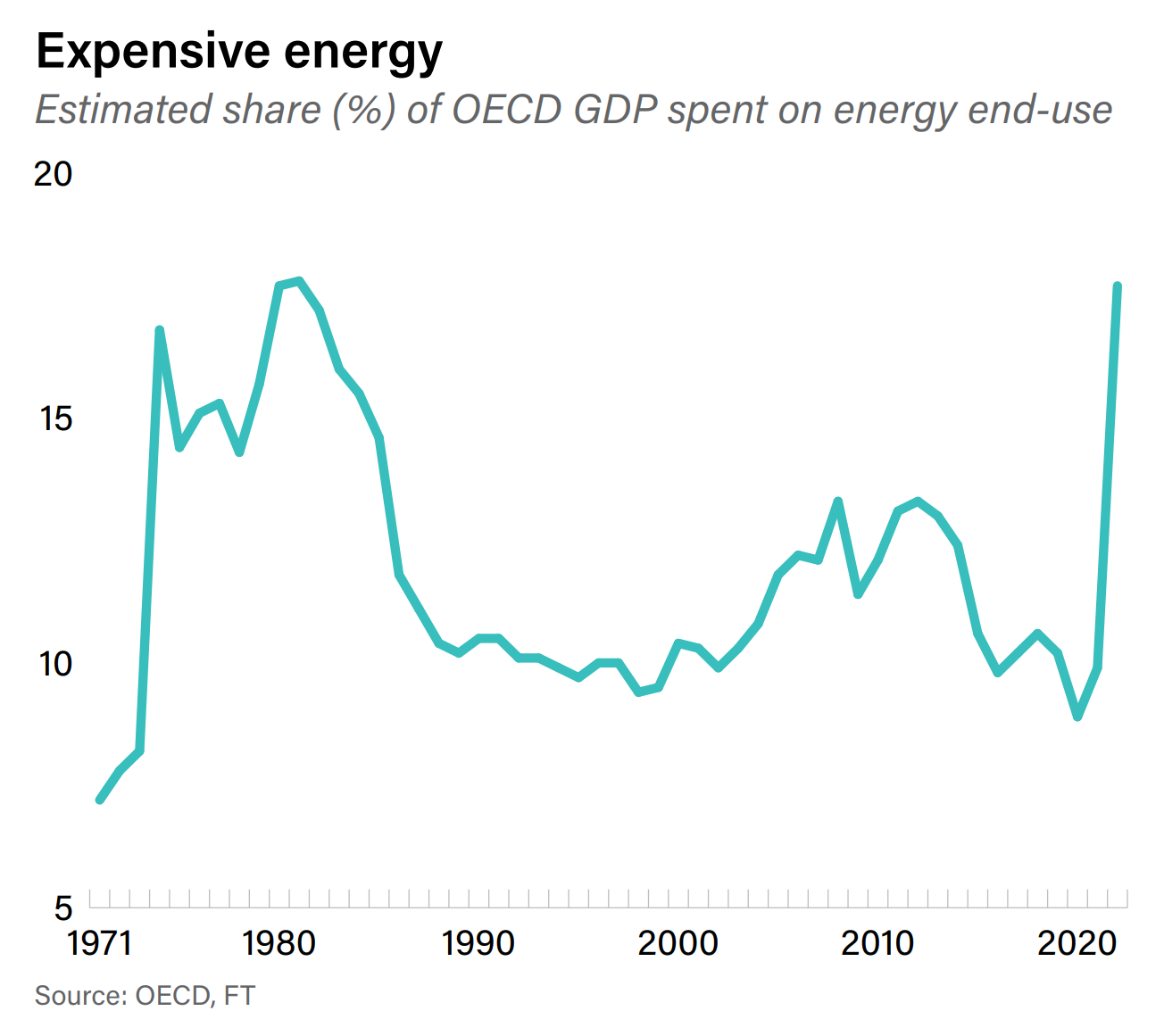

to cushion the fall in incomes with extraordinary fiscal and monetary stimulus at the same time that it disrupted global supply. Then, just as the United States and Europe were coming out of the pandemic thanks to vaccines, China doubled down on its zero-Covid policy, locking down the global economy’s most important manufacturing and shipping hubs. Finally, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the West’s sanctions in response put a strain on the global supply of energy, food, and fertilizer. This unprecedented confluence of overlapping shocks pushed inflation to levels most countries hadn’t seen in nearly 50 years. Graphic: Eurasia Group

And now, our top risks [Top Risks 2023].

- ROGUE RUSSIA: A humiliated Russia will turn from global player into the world’s most dangerous rogue state, posing a serious security threat to Europe, the United States, and beyond.

- MAXIMUM XI: Xi Jinping emerged from China’s 20th Party Congress in October 2022 with a grip on power unrivaled since Mao Zedong.

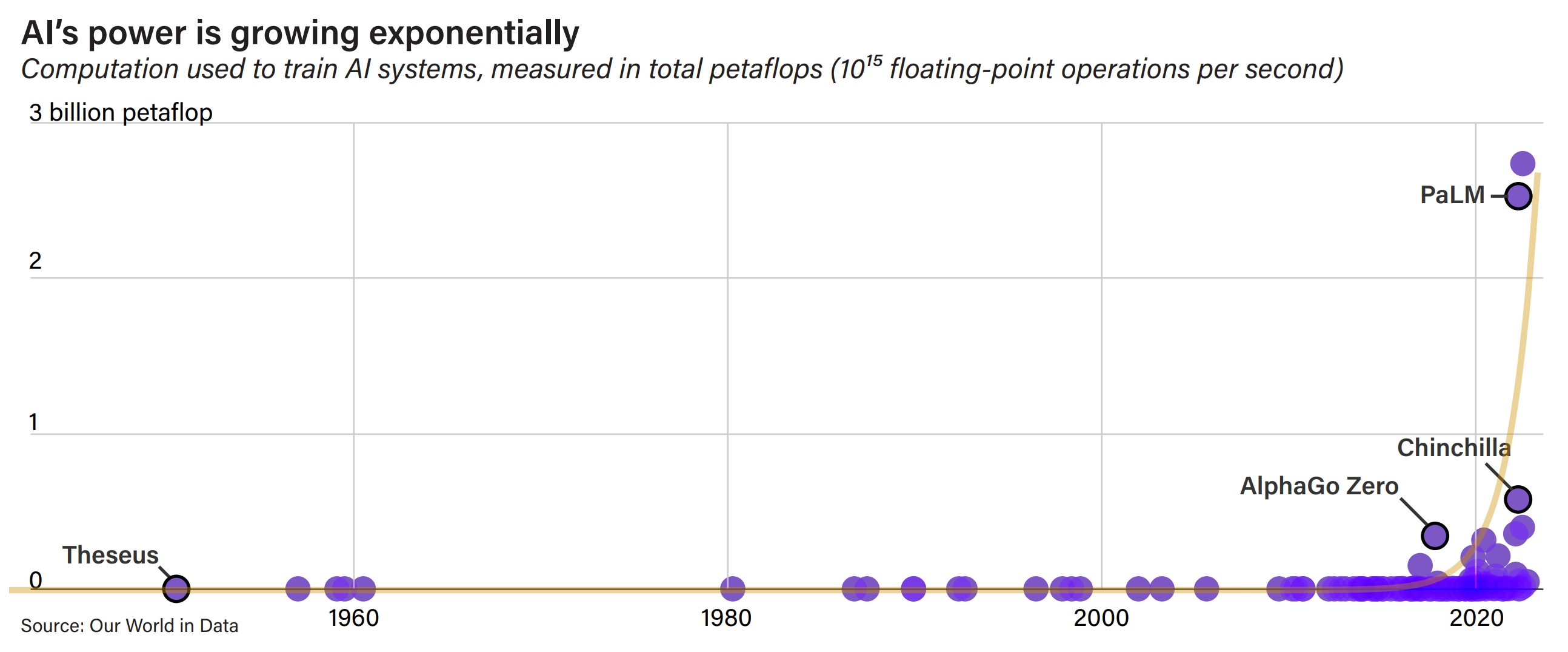

- WEAPONS OF MASS DISRUPTION: New technologies will be a gift to autocrats bent on undermining democracy abroad and stifling dissent at home.

- INFLATION SHOCKWAVES: Rising interest rates and global recession will raise the risk of emerging-market crises.

- IRAN IN A CORNER: The chance of regime collapse is low, but it’s higher than at any point in the past four decades.

- ENERGY CRUNCH: Higher oil prices will also increase frictions between OPEC+ and the United States.

- ARRESTED GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT: Women and girls will suffer the most, losing hard-earned rights, opportunities, and security.

- DIVIDED STATES OF AMERICA: There is a continuing risk of political violence in the US, even as some who participated in the Capitol riots go to prison.

- TIK TOK BOOM: Gen Z has both the ability and the motivation to organize online to reshape corporate and public policy, making life harder for multinationals everywhere and disrupting politics with the click of a button.

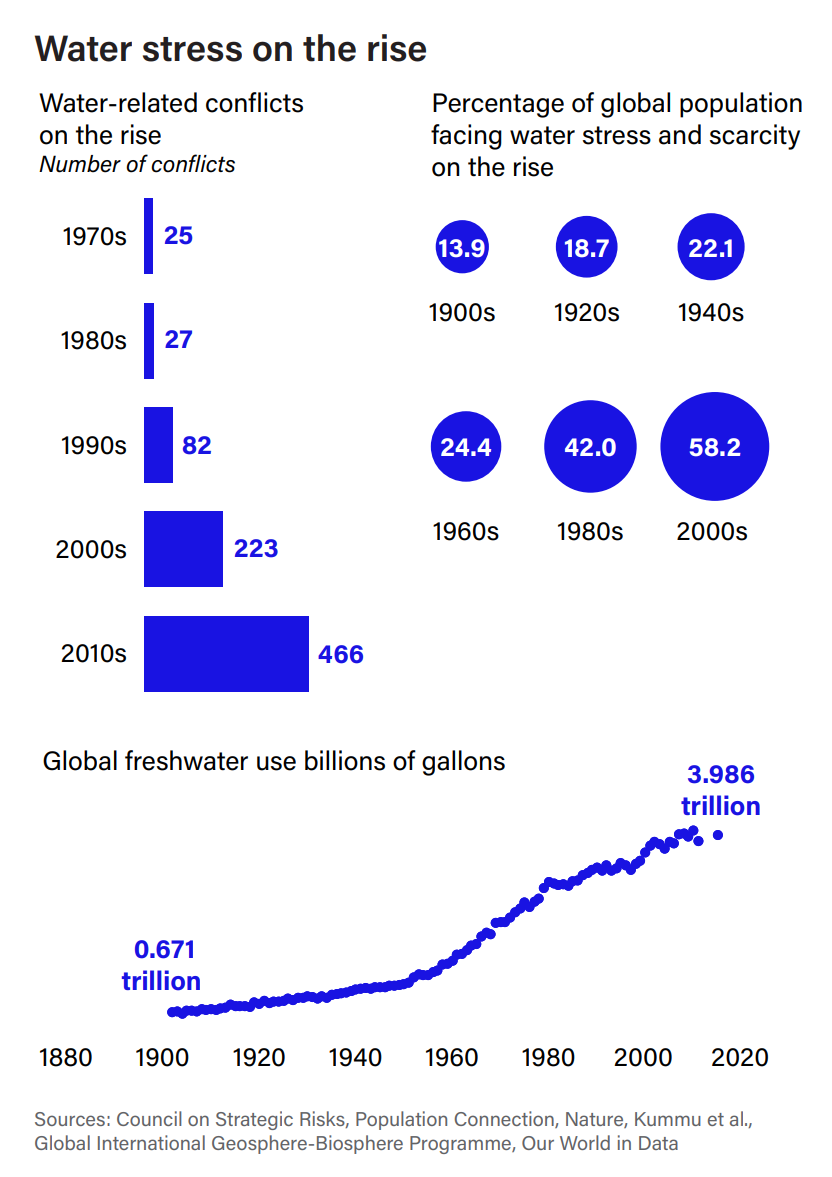

- WATER STRESS: This year, water stress will become a global and systemic challenge…while governments will still treat it as a temporary crisis.

RED HERRINGS: Cracks in support for Ukraine. EU political dysfunction. Taiwan crisis. Tech tit-for-tat.

Conclusion

We try not to think too hard about writing a report on where the world is going (put it that way, and it feels like a daunting task). But it’s not about prediction. You start with where the world is, really is, and to the extent that you get that assessment right, it constrains more outcomes than any crystal ball ever could. In many ways, Top Risks is about the art of what’s not possible.

We learn as much about ourselves as the world in the process. What biases are we holding on to that need to be challenged? What are the things we think we know that aren’t really so? And what would make us wrong?

We hope we’ve addressed these issues—we’ve certainly tried! As always, we’ll be keeping the Top Risks on our homepage all year, so we can keep ourselves honest … and then come back in December and see how we’ve done.

In the meantime, a heartfelt thanks for your support for the 25 years since we started Eurasia Group. It’s a milestone that makes us stop for a moment. Yes, we’re older, if not wiser (though it helps that we were children when we founded this thing). We’re definitely more grateful.

Our very best wishes for our year ahead.

Ian and Cliff