Inside the Saudi strategy to keep the world hooked on oil – “People would like us to give up on investment in hydrocarbons. But no.”

By Hiroko Tabuchi

21 November 2022

(The New York Times) – Shimmering in the desert is a futuristic research center with an urgent mission: Make Saudi Arabia’s oil-based economy greener, and quickly. The goal is to rapidly build more solar panels and expand electric-car use so the kingdom eventually burns far less oil.

But Saudi Arabia has a far different vision for the rest of the world. A major reason it wants to burn less oil at home is to free up even more to sell abroad. It’s just one aspect of the kingdom’s aggressive long-term strategy to keep the world hooked on oil for decades to come and remain the biggest supplier as rivals slip away.

In recent days, Saudi representatives pushed at the United Nations global climate summit in Egypt to block a call for the world to burn less oil, according to two people present at the meeting, saying that the summit’s final statement “should not mention fossil fuels.” The effort prevailed: After objections from Saudi Arabia and a few other oil producers, the statement failed to include a call for nations to phase out fossil fuels.

The kingdom’s plan for keeping oil at the center of the global economy is playing out around the world in Saudi financial and diplomatic activities, as well as in the realms of research, technology and even education. It is a strategy at odds with the scientific consensus that the world must swiftly move away from fossil fuels, including oil and gas, to avoid the worst consequences of global warming.

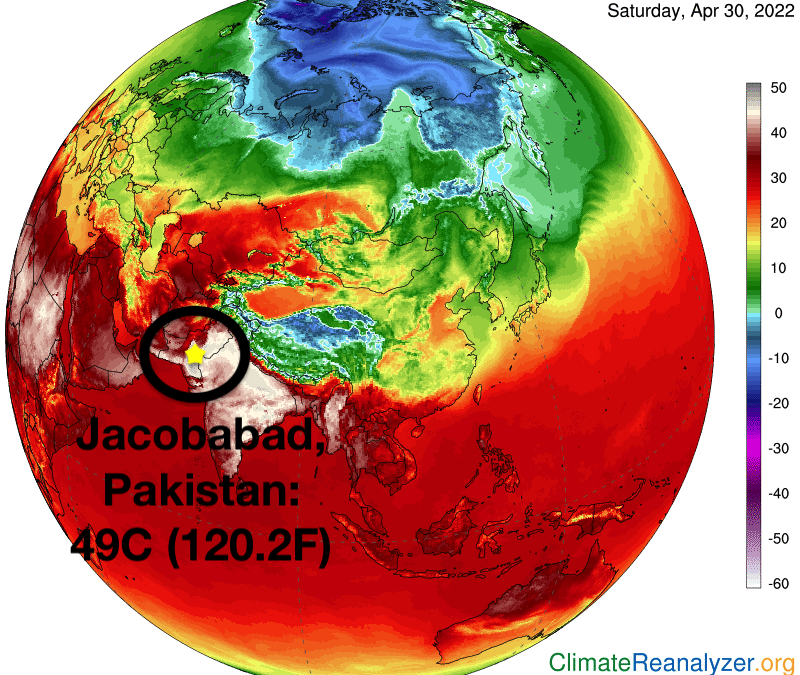

The dissonance cuts to the heart of the Saudi kingdom. The government-controlled oil company, Saudi Aramco, already produces one out of every 10 of the world’s barrels of oil and envisions a world where it will be selling even more. Yet climate change and rising temperatures are already threatening life in the desert kingdom like few other places in the world.

Saudi Aramco has become a prolific funder of research into critical energy issues, financing almost 500 studies over the past five years, including research aimed at keeping gasoline cars competitive or casting doubt on electric vehicles, according to the Crossref database, which tracks academic publications. Aramco has collaborated with the United States Department of Energy on high-profile research projects including a six-year effort to develop more efficient gasoline and engines, as well as studies on enhanced oil recovery and other methods to bolster oil production.

Aramco also runs a global network of research centers including a lab near Detroit where it is developing a mobile “carbon capture” device — equipment designed to be attached to a gasoline-burning car, trapping greenhouse gases before they escape the tailpipe. More widely, Saudi Arabia has poured $2.5 billion into American universities over the past decade, making the kingdom one of the nation’s top contributors to higher education.

Saudi interests have spent close to $140 million since 2016 on lobbyists and others to influence American policy and public opinion, making it one of the top countries spending on U.S. lobbying, according to disclosures to the Department of Justice tallied by the Center for Responsive Politics.

Much of that has focused on bolstering the kingdom’s overall image, particularly after the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 by Saudi operatives. But the Saudi effort has also extended to building alliances in American Corn Belt states that produce ethanol — a product also threatened by electric cars.

Behind closed doors at global climate talks, the Saudis have worked to obstruct climate action and research, in particular objecting to calls for a rapid phaseout of fossil fuels. In March, at a United Nations meeting with climate scientists, Saudi Arabia, together with Russia, pushed to delete a reference to “human-induced climate change” from an official document, in effect disputing the scientifically established fact that the burning of fossil fuels by humans is the main driver of the climate crisis.

“People would like us to give up on investment in hydrocarbons. But no,” said Amin Nasser, Saudi Aramco’s chief executive, because such a move would only wreak havoc with oil markets. The bigger threat was the “lack of investment in oil and gas,” he said.

In a statement, the Saudi Ministry of Energy said it expected that hydrocarbons such as oil, gas and coal would “continue to be an essential part of the global energy mix for decades,” but at the same time the kingdom had “made significant investments in measures to combat climate change.” The statement added, “Far from blocking progress at climate change talks, Saudi Arabia has long played a major role” in negotiations as well as in oil and gas industry groups working to lower emissions.

And Saudi Arabia is hedging its bets. The government has invested in Lucid, the American electric vehicle company, and recently said it would form its own electric vehicle company, Ceer. It is investing in hydrogen, a cleaner alternative to oil and gas.

Still, the green transition at home has been slow. Saudi Arabia still generates less than 1 percent of its electricity from renewables, and it isn’t clear how it plans to plant billions of trees in one of the world’s driest regions.

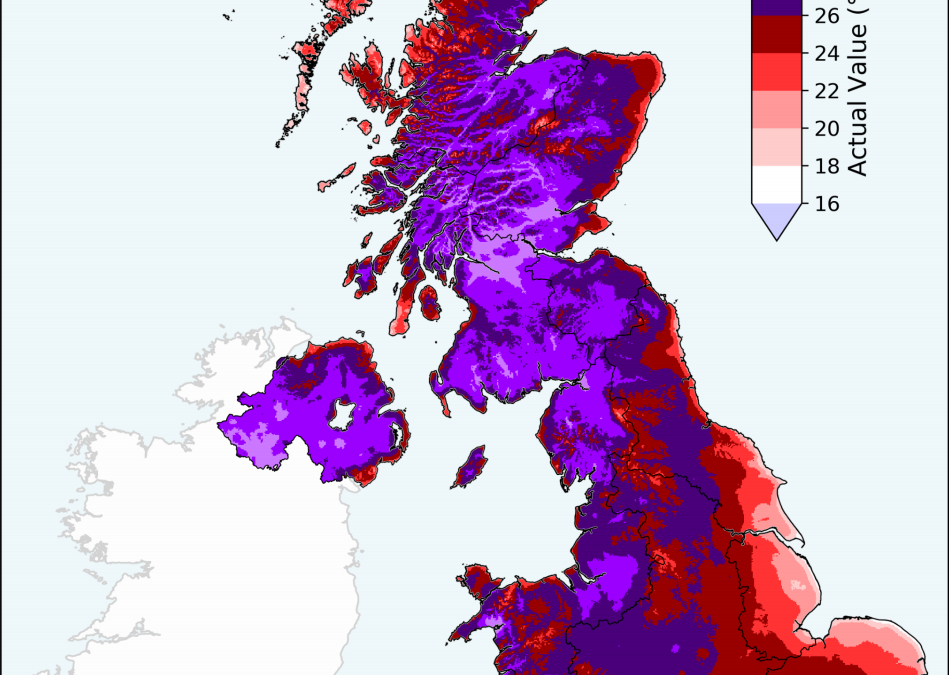

All the while, the climate threat is getting harder to ignore. At current rates, human survival in the region will be impossible without continuous access to air-conditioning, researchers said last year.

Among researchers at the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, a space station-like compound powered by 20,000 solar panels where discussion focuses on solar and wind projects or technologies like carbon capture, the more immediate trade-off is clear.

“If we keep consuming our own oil,” said Anvita Arora, who directs the center’s transport team, “we won’t have any oil left to sell.” [more]