Fentanyl’s scourge plainly visible on streets of Los Angeles

By Jae C. Hong and Brian Melley

28 November 2022

LOS ANGELES (AP) – In a filthy alley behind a Los Angeles doughnut shop, Ryan Smith convulsed in the grips of a fentanyl high — lurching from moments of slumber to bouts of violent shivering on a warm summer day.

When Brandice Josey, another homeless addict, bent down and blew a puff of fentanyl smoke his way in an act of charity, Smith sat up and slowly opened his lip to inhale the vapor as if it was the cure to his problems.

Smith, wearing a grimy yellow T-shirt that read “Good Vibes Only,” reclined on his backpack and dozed the rest of the afternoon on the asphalt, unperturbed by the stench of rotting food and human waste that permeated the air.

For too many people strung out on the drug, the sleep that follows a fentanyl hit is permanent. The highly addictive and potentially lethal drug has become a scourge across America and is taking a toll on the growing number of people living on the streets of Los Angeles.

Nearly 2,000 homeless people died in the city from April 2020 to March 2021, a 56% increase from the previous year, according to a report released by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Overdose was the leading cause of death, killing more than 700.

Fentanyl was developed to treat intense pain from ailments like cancer. Use of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that is cheap to produce and is often sold as is or laced in other drugs, has exploded. Because it’s 50 times more potent than heroin, even a small dose can be fatal.

It has quickly become the deadliest drug in the nation, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. Two-thirds of the 107,000 overdose deaths in 2021 were attributed to synthetic opioids like fentanyl, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. […]

Drug abuse can be a cause or symptom of homelessness. Both can also intersect with mental illness.

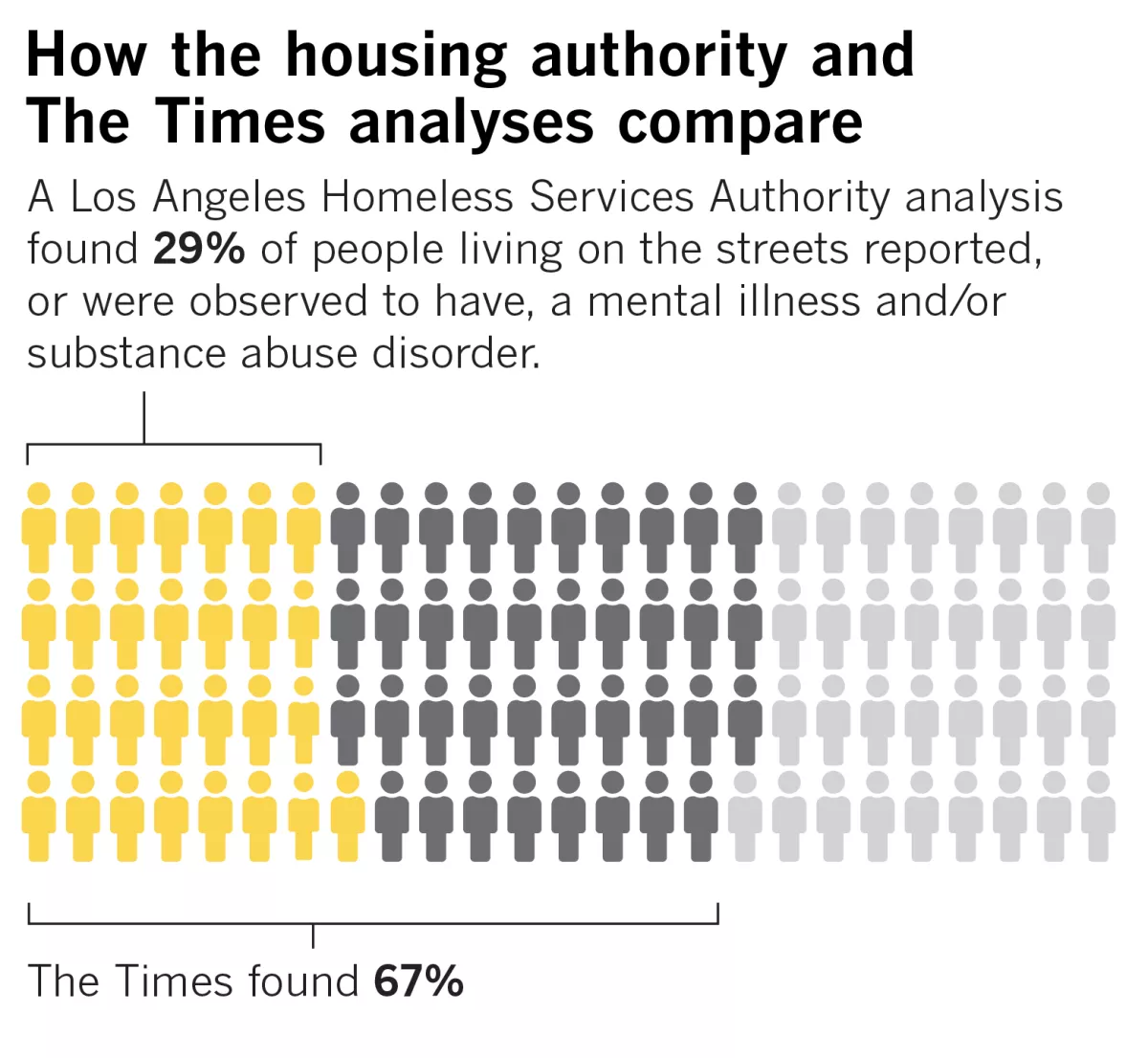

A 2019 report by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority found about a quarter of all homeless adults in Los Angeles County had mental illnesses and 14% had a substance use disorder. That analysis only counted people who had a permanent or long-term severe condition. Taking a broader interpretation of the same data, the Los Angeles Times found about 51% had mental illnesses and 46% had substance use disorders.

Billions of dollars are being spent to alleviate homelessness in California but treatment is not always funded.

A controversial bill signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom could improve that by forcing people suffering from severe mental illness into treatment. But they need to be diagnosed with a certain disorder such as schizophrenia and addiction alone doesn’t qualify.

Help is available but it is outpaced by the magnitude of misery on the streets.

Rita Richardson, a field supervisor with LA Door, a city addiction-prevention program that works with people convicted of misdemeanors, hands out socks, water, condoms, snacks, clean needles, and flyers at the same hotspots Monday through Friday. She hopes the consistency of her visits will encourage people to get help.

“Then hopefully the light bulb comes on. It might not happen this year. It might not happen next year. It might take several years,” said Richardson, a former homeless addict. ”My goal is to take them from the dark to the light.”

Parts of Los Angeles have become scenes of desperation with men and women sprawled on sidewalks, curled up on benches and collapsed in squalid alleys. Some huddle up smoking the drug, others inject it.

Armando Rivera, 33, blew out white puffs to attract addicts in the alley where Smith was sleeping. He needed to sell some dope to buy more. Those without enough money to support their habit, hovered around him, hoping for a free hit. Rivera showed no mercy.

Catano couldn’t sell the chair, but eventually she sold the fabric softener to a street vendor for $5.

It was enough money for another high. [more]

Fentanyl’s scourge plainly visible on streets of Los Angeles