The global expansion of authoritarian rule – “The present threat to democracy is the product of 16 consecutive years of decline in global freedom”

By Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz

24 February 2022

(Freedom House) – Global freedom faces a dire threat. Around the world, the enemies of liberal democracy—a form of self-government in which human rights are recognized and every individual is entitled to equal treatment under law—are accelerating their attacks. Authoritarian regimes have become more effective at co-opting or circumventing the norms and institutions meant to support basic liberties, and at providing aid to others who wish to do the same. In countries with long-established democracies, internal forces have exploited the shortcomings in their systems, distorting national politics to promote hatred, violence, and unbridled power. Those countries that have struggled in the space between democracy and authoritarianism, meanwhile, are increasingly tilting toward the latter. The global order is nearing a tipping point, and if democracy’s defenders do not work together to help guarantee freedom for all people, the authoritarian model will prevail.

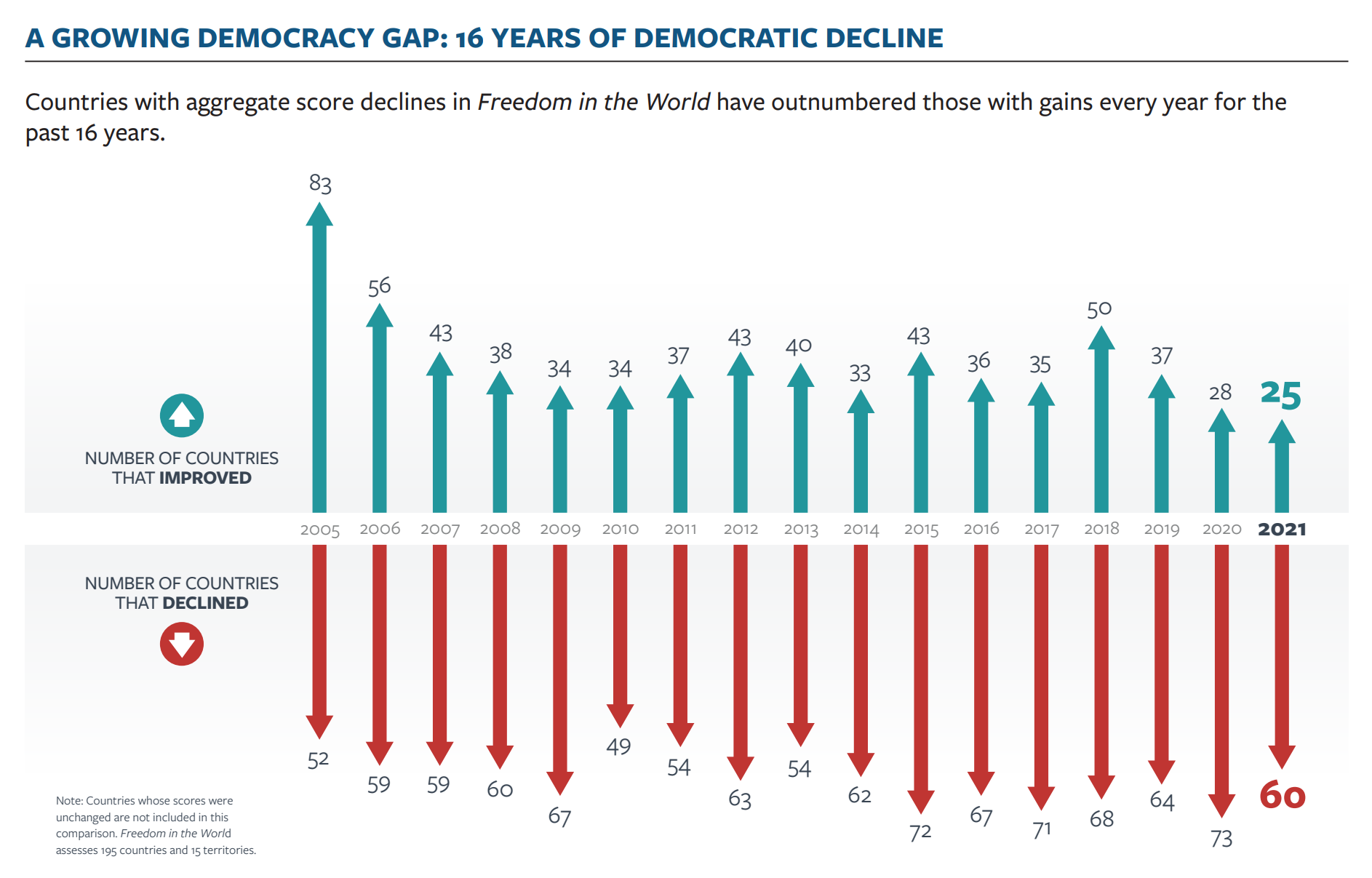

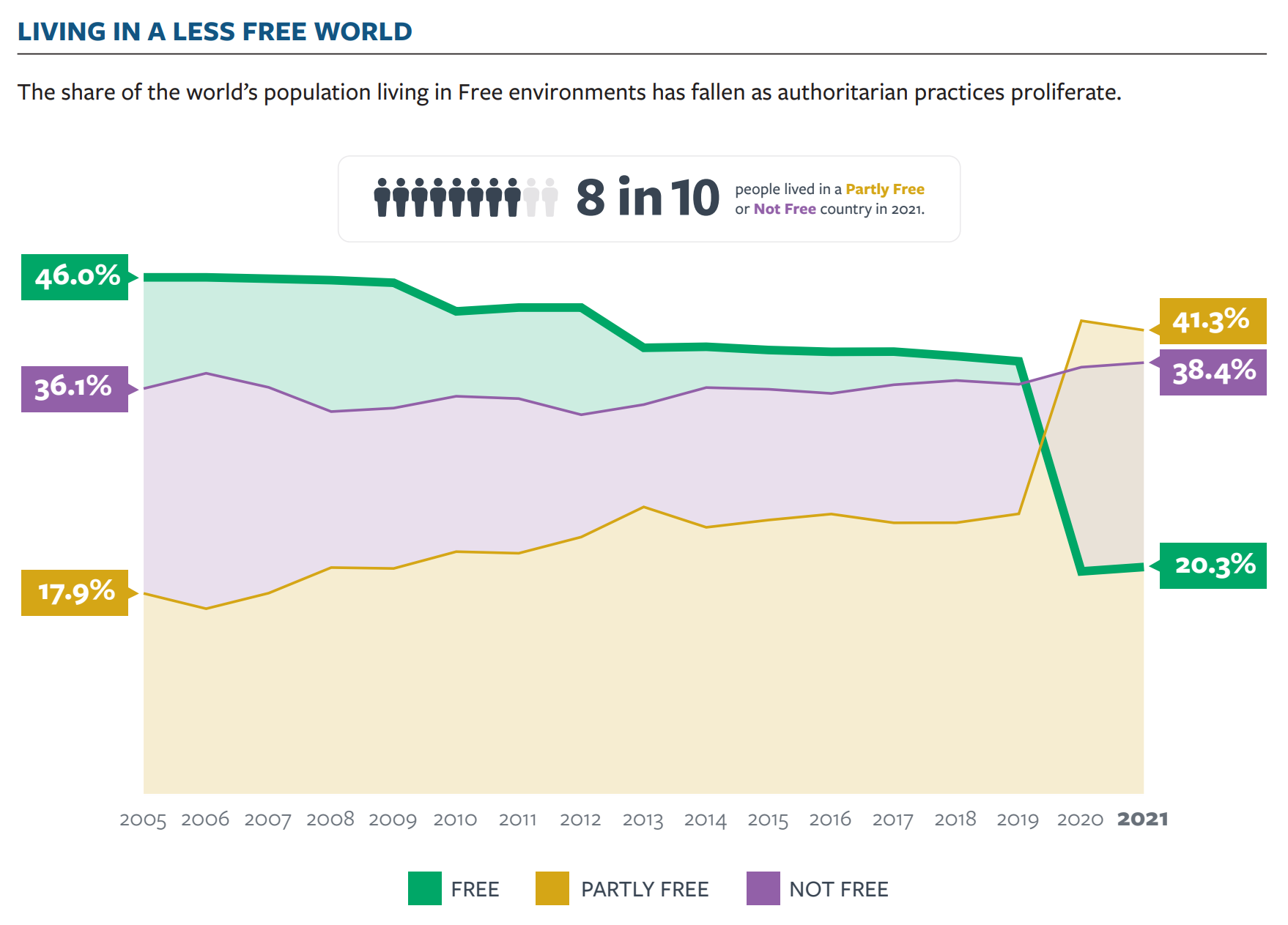

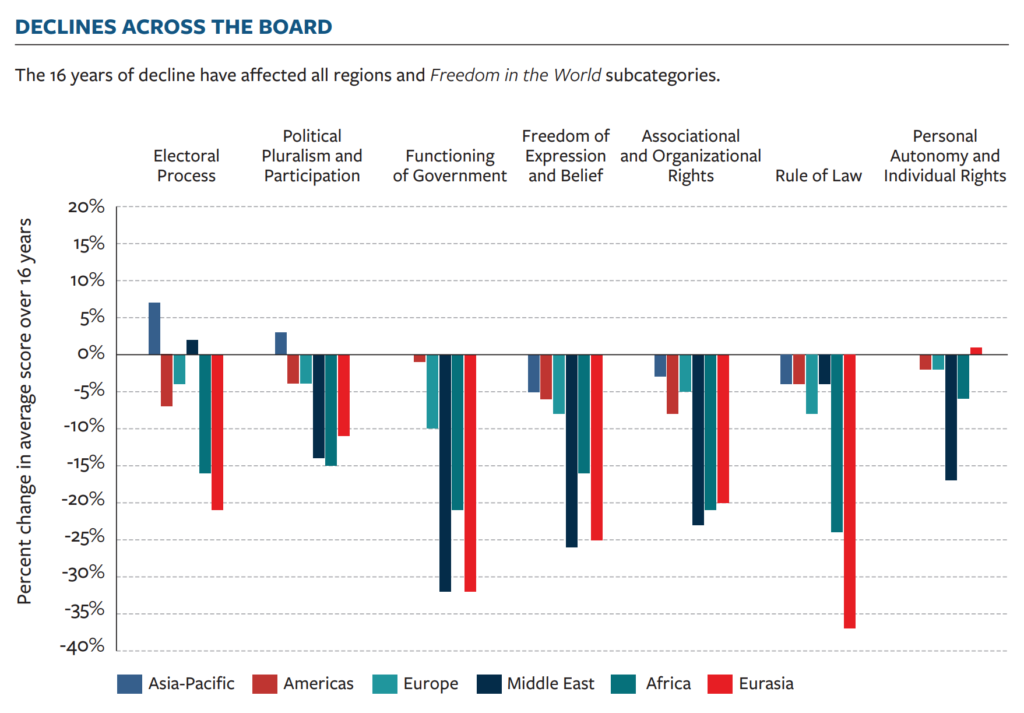

The present threat to democracy is the product of 16 consecutive years of decline in global freedom. A total of 60 countries suffered declines over the past year, while only 25 improved. As of today, some 38 percent of the global population live in Not Free countries, the highest proportion since 1997. Only about 20 percent now live in Free countries.

During this period of democratic decline, checks on abuse of power and human rights violations have eroded. In the decades after World War II, the United Nations and other international institutions promoted the notion of fundamental rights, and democracies offered support—however unevenly—in their domestic and foreign policies as they strove to create an open international system built on shared resistance to totalitarianism. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, leaders of countries in transition felt compelled to publicly embrace the same ideals in order to win acceptance in the international community, even if their commitment was only skin deep. Governments that relied on external economic or military support had to stage at least superficially credible elections and respect some institutional checks on their power, among other concessions, to maintain their good standing.

For much of the 21st century, however, democracy’s opponents have labored persistently to dismantle this international order and the restraints it imposed on their ambitions. The fruits of their exertions are now apparent. The leaders of China, Russia, and other dictatorships have succeeded in shifting global incentives, jeopardizing the consensus that democracy is the only viable path to prosperity and security, while encouraging more authoritarian approaches to governance.

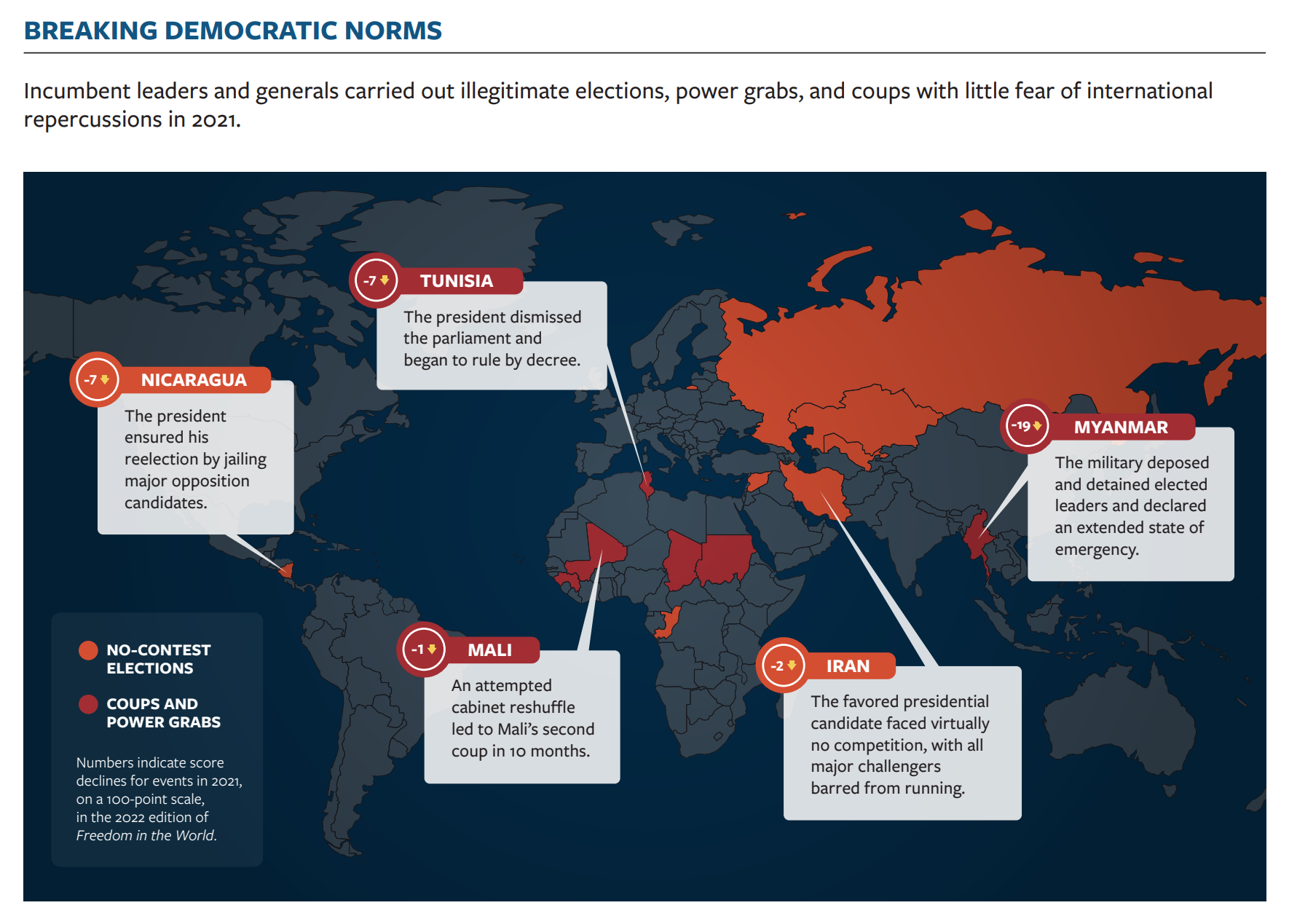

Countries in every region of the world have been captured by authoritarian rulers in recent years. In 2021 alone, Nicaragua’s incumbent president won a new term in a tightly orchestrated election after his security forces arrested opposition candidates and deregistered civil society organizations. Sudan’s generals seized power once again, reversing democratic progress made after the 2019 ouster of former dictator Omar al-Bashir. And as the United States abruptly withdrew its military from Afghanistan, the elected government in Kabul collapsed and gave way to the Taliban, returning the country to a system that is diametrically opposed to democracy, pluralism, and equality.

At the same time, democracies are being harmed from within by illiberal forces, including unscrupulous politicians willing to corrupt and shatter the very institutions that brought them to power. This was arguably most visible last year in the United States, where rioters stormed the Capitol on January 6 as part of an organized attempt to overturn the results of the presidential election. But freely elected leaders from Brazil to India have also taken or threatened a variety of antidemocratic actions, and the resulting breakdown in shared values among democracies has led to a weakening of these values on the international stage.

It is now impossible to ignore the damage to democracy’s foundations and reputation. The regimes of China, Russia, and other authoritarian countries have gained enormous power in the international system, and freer countries have seen their established norms challenged and fractured. The current state of global freedom should raise alarm among all who value their own rights and those of their fellow human beings. To reverse the decline, democratic governments need to strengthen domestic laws and institutions while taking bold, coordinated action to support the struggle for democracy around the world. In less free countries, democrats must unite to resist the encroachment of unchecked power and work toward expanding freedom for all individuals. Only global solidarity among democracy’s defenders can successfully counter the combined aggression of its adversaries.

Popular demand for democracy remains strong. From Sudan to Myanmar, people continue to risk their lives in the pursuit of freedom in their countries. Many others undertake dangerous journeys in order to live freely elsewhere. Democratic governments and societies must harness and support this common desire for fundamental rights and build a world in which it is ultimately fulfilled.

The promotion of autocratic norms

Autocrats have created a more favorable international environment for themselves over the past decade and a half, empowered by their own political and economic might as well as waning pressure from democracies. The alternative order is not based on a unifying ideology or personal affinity among leaders. It is not designed to serve the best interests of populations, or to enable people to improve their own lives. Instead it is grounded in autocrats’ shared interest in minimizing checks on their abuses and maintaining their grip on power. A world governed by this order would in reality be one of disorder, replete with armed conflict, lawless violence, corruption, and economic volatility. Such global instability and insecurity would have a significant cost in human lives.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) plays a leading role in promoting autocratic norms. Citing its self-serving interpretation of state sovereignty, the party strives to carve out space for incumbent governments to act as they choose without oversight or consequences. It offers an alternative to democracies as a source of international support and investment, helping would-be autocrats to entrench themselves in office, adopt aspects of the CCP governance model, and enrich their regimes while ignoring principles like transparency and fair competition. At the same time, the CCP has used its vast economic clout and even military threats to suppress international criticism of its own violations of democratic principles and human rights, for instance by punishing governments and other foreign entities that criticize its demolition of civil liberties in Hong Kong or question its expansive territorial claims.

In 2021, the CCP further extended the scope of speech it would not tolerate, employing economic and technological leverage to pressure governments, international institutions, and the private sector to echo its preferred narratives. Although new evidence indicated that party leader Xi Jinping and other top officials had a hand in planning and implementing widespread crimes against humanity and acts of genocide against ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang, many foreign actors, including some democracies, toed the CCP line. A Marriott hotel in the Czech Republic declined to host a November 2021 World Uyghur Congress gathering, arguing that it preferred to observe “political neutrality.” New Zealand’s Parliament refrained from identifying Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang as a genocide after the trade minister voiced concerns that such language would hinder economic relations with China. Such threats are credible given Beijing’s past reprisals against foreign companies and nations, including the imposition of tariffs on Australian exports after Canberra called for an independent investigation into the origin of COVID-19.

Dropping the pretense of competitive elections

Elections, even when critically flawed, have long given authoritarian leaders a veneer of legitimacy, both at home and abroad. As international norms shift in the direction of autocracy, however, these exercises in democratic theater have become increasingly farcical.

In the run-up to Russia’s September 2021 parliamentary elections, the regime of President Vladimir Putin dispelled the illusion of competition by imprisoning opposition leader Aleksey Navalny and tarring his movement as “extremist,” which prevented any candidates who were even loosely associated with it from running for office. The balloting itself was marred by irregularities and restrictions on independent observers, and technology firms were forced to remove a Navalny-backed mobile app meant to inform opposition voters about the strongest candidates in their area. A law on “foreign agents” was also expanded ahead of the elections, restricting the activities of independent media as well as individuals who were critical of the regime.

The November 2021 presidential election in Nicaragua was similarly uncompetitive. President Daniel Ortega’s authoritarian government refused to implement electoral reforms recommended by the Organization for American States, including measures that would have made the Supreme Electoral Council more independent, established more transparency in the voter-registration and vote-counting processes, and allowed independent and credible international electoral observers to monitor the polls. Instead, during the preceding year, the government passed laws designed to target the opposition, including a “foreign agents” law inspired by the Russian legislation. The regime also canceled the registration of nearly 50 organizations, effectively quashing independent civil society, and arrested at least seven potential opposition candidates on charges including treason.

The December 2021 Legislative Council elections in Hong Kong underscored Beijing’s success in dismantling the territory’s semidemocratic institutions. Like Putin and Ortega, the CCP and its allies in the Hong Kong government laid the groundwork for a tightly controlled process, enacting an electoral “reform” that sharply diminished direct suffrage and allowed authorities to exclude candidates based on political criteria, arresting and detaining opposition leaders under the draconian National Security Law, and forcing independent media outlets to shut down. It therefore surprised no one when pro-Beijing candidates dominated the new legislature, despite a long history of robust voter support for prodemocracy candidates. [more]

https://www.vox.com/2015/3/23/8279397/kolomoisky-oligarch-ukraine-militia