Dying crops, spiking energy bills, showers once a week: in South America, global warming brings new normal of water scarcity – “What we’re seeing today is as if the future has already arrived”

By Diego Laje, Anthony Faiola, and Ana Vanessa Herrero

24 September 2021

BUENOS AIRES (The Washington Post) – Sergio Koci’s sunflower farm in the lowlands of northern Argentina has survived decades of political upheaval, runaway inflation and the coronavirus outbreak. But as a series of historic droughts deadens vast expanses of South America, he fears a worsening water crisis could do what other calamities couldn’t: Bust his third-generation agribusiness.

“When you have one bad year, you can face it,” Koci said. Some of his 20,000 acres rest near the mighty Paraná River, where water levels have reached lows not seen since 1944. On the back of two years of drought-related crop losses, he said, the continuing dryness is now set to reduce his sunflower yields this year by 65 percent.

“When you have three bad years, you don’t know if there will even be another year,” he said.

From the frigid peaks of Patagonia to the tropical wetlands of Brazil, worsening droughts this year are slamming farmers, shutting down ski slopes, upending transit and spiking prices for everything from coffee to electricity.

So low are levels of the Paraná running through Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina that some ranchers are herding cattle across dried-up riverbeds typically lined with cargo-toting barges. Raging wildfires in Paraguay have brought acrid smoke to the limits of the capital. Earlier this year, the rushing cascades of Iguazu Falls on the Brazilian-Argentine frontier reduced to a relative drip.

The droughts this year are extensions of multiyear water shortages, with causes that vary from country to country. Yet for much of the region, the droughts are moving up the calendar on climate change — offering a taste of the challenges ahead in securing an increasingly precious commodity: water.

“It’s an escalating problem, and the fact that we’re seeing more and more of these events, and more extreme events, is not a coincidence,” said Lisa Viscidi, energy and climate expert with the Washington-based Inter-American Dialogue. “It’s definitely because we’re seeing the effects of climate change.”

The region is one of many across the globe being struck by severe drought. Hot spots severe enough to cause widespread crop losses, water shortages and elevated fire risk are now present in every continent outside Antarctica. Farmers in Arizona are curbing water use amid a catastrophic decline of the Colorado River. California melons are withering on their vines. The drought in Madagascar is being partly blamed for what the United Nations is calling the world’s first climate famine. […]

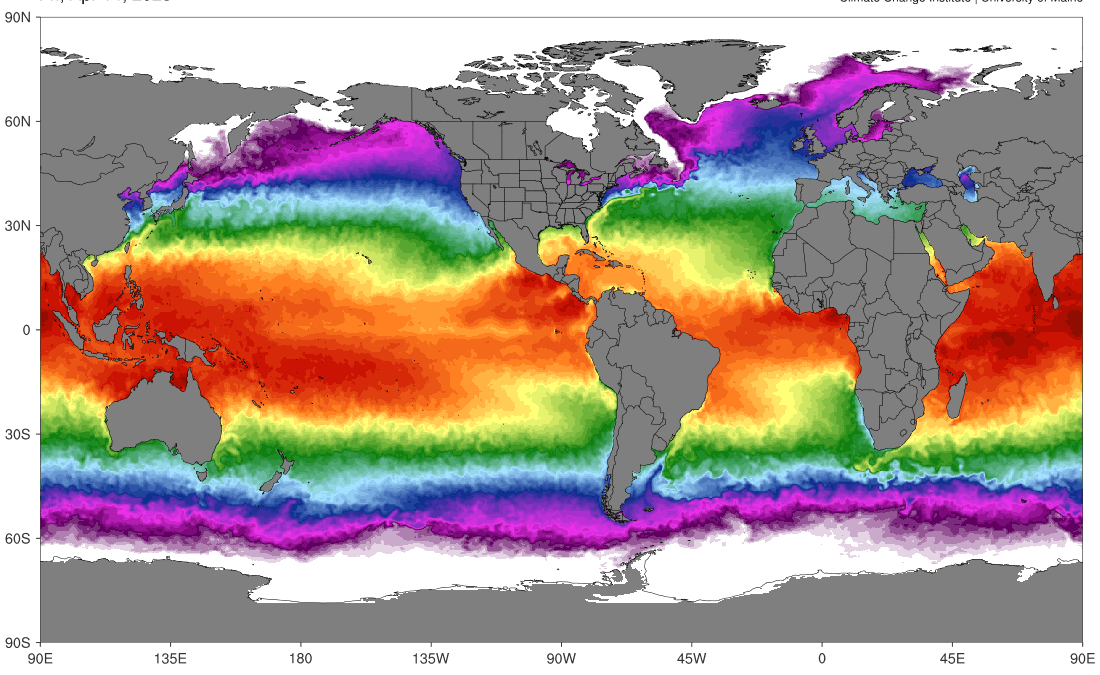

In Chile, a nation caught in the vortex of a 13-year drought, its longest and most severe in 1,000 years, a “blob” of warm water in the southwest Pacific the size of the continental United States is disturbing rain patterns, pushing storm tracks southward over the Drake Passage and Antarctica. Scientists say greenhouse gases have exacerbated the drying trend, putting Chile at the forefront of the region’s water crisis.

“We are one of the regions of the globe where you can see that climate models coincide in their predictions, that by the end of the 21st century, we’ll have on average 30 percent less rainfall than today,” said Duncan Christie, a paleoclimatologist at the Austral University of Chile. “What we’re seeing today is as if the future has already arrived in central Chile.”

The Chilean government has declared an agricultural emergency in 8 of its 16 regions and is offering aid to stricken farmers. Agriculture Minister María Emilia Undurraga said some regions are registering rainfall losses of between 62 and 80 percent.

If conditions do not improve, Chile’s copper mining industry — responsible for 10 percent of the nation’s economic output, and heavily reliant on water for processing — could see a drop in production of between 2.6 and 3.4 percent this year, amounting to losses of up to $1.7 billion, according to Manuel Viera, president of the Chilean Mining Chamber.

“Our economy very much depends on copper, and this is going to have an impact,” Viera said. “Without water, there is no mining.” [more]