Regulators refuse to step in as U.S. workers languish in extreme heat

By Ariel Wittenberg and Zack Colman

8 August 2021

(POLITICO) – When it gets so hot that the hallucinations start, and her eyes hurt and her spit begins to foam, construction worker Sharon Medina disappears behind a wall of co-workers to sneak a sip of water.

She discovered the hard way not to complain to the boss about working in the heat. Witnessing a colleague get fired after collapsing while demolishing flooded, moldy Houston homes in Hurricane Harvey’s aftermath, Medina learned to stay quiet and keep her jobs.

“A lot of the employers forget we are people, even when they see we are suffering,” Medina, 47, said.

Medina presses on in a city where summer temperatures and humidity routinely feel hotter than 100 degrees. She is only allowed 15 minutes for lunch. She has barely any time to go to the bathroom, even as she remodels them in other peoples’ homes.

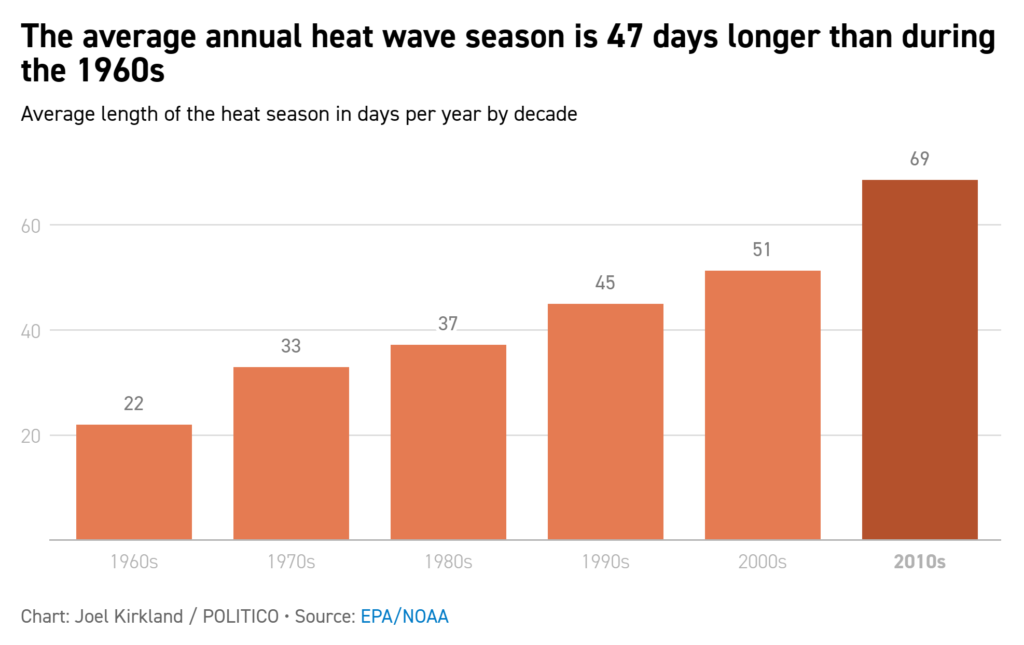

There is no federal standard protecting people like Medina from heat, which killed 815 workers between 1992 and 2017 and seriously injured 70,000 more, according to federal records. More heat deaths are likely in the coming years as climate change turbocharges temperatures to make heat waves even hotter and last longer. The Western U.S. suffered from punishing temperatures this summer, rising higher than they normally would so early in the season. The record-breaking temperatures in the Pacific Northwest would have been “virtually impossible without human-caused climate change,” according to modeling and global observations.

The heat wave in June killed more than 80 people in Oregon alone. [And almost 600 people in British Columbia. –Des] Three of them were workers, including a middle-aged trainee at a Walmart distribution center who collapsed toward the end of his shift after stumbling and having difficulty speaking. The death toll prompted the state to issue emergency worker protections, with Democratic Gov. Kate Brown saying she was “concerned that our record-breaking heat wave” was “a harbinger of what’s to come.”

But the Occupational Safety and Health Administration responsible for protecting laborers from workplace hazards has ignored three recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that it create a much-needed floor, a temperature level above which conditions are deemed inherently unsafe for worker safety. OSHA has also denied similar petitions from occupational and environmental groups.

A four-month investigation by POLITICO and E&E News found that the agency’s reluctance has extended through nine administrations, with bureaucracy and lack of political will combining to continually kick the can down the road. …

Without an enforceable heat standard, more workers across the country languished in stifling conditions this summer. There was nothing protecting them beyond federal guidance that merely encourages employers to provide proven life-saving measures like water breaks and cooling areas. […]

Laborers are particularly vulnerable to heat due to the strenuous nature of their work. Physical activity makes it difficult for the body to cool itself down, which gets dangerous when temperatures and humidity rise. The results of overheating can range from dizziness, nausea, vomiting and a fast heart rate to deadly heat stroke. Heat can exacerbate preexisting respiratory and heart conditions, and it can hit lower-income workers particularly hard if they’re less able to afford to run air conditioning on hot nights, straining their bodies during restless sleep.

Some sectors face starker dangers. Construction workers are just 6 percent of the American workforce while accounting for 36 percent of all occupational heat-related deaths. But the heat threat is spreading to other occupations and locations, too. People working at indoor warehouses that lack air conditioning or in meatpacking facilities are at risk, especially as cooler northern latitudes face the effect of warming temperatures.

But even if the Biden administration decides to write a standard, it’s an open question whether OSHA is up to the challenge.

Staffing and workplace inspections have plummeted, raising concerns about whether it could realistically police a new heat regulation. In 1990, there was one OSHA employee per 51,765 workers; in 2019 there was one OSHA employee per 88,977 workers, according to an analysis by the Revolving Door Project, a progressive policy group.

“Obviously, the standard is useless without enforcement,” said Juley Fulcher, a worker health advocate for Public Citizen, a government watchdog group that has petitioned OSHA for a heat safety standard. [more]

Regulators refuse to step in as workers languish in extreme heat